Two years later, Providence staffers reflect as the ‘human tragedy’ of a pandemic leaves its mark

It’s a milestone that comes with a grim death toll.

Two years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, more than 6 million people have lost their lives from the virus across the world. In the United States, more than 967,000 people have died from the virus, according to the Johns Hopkins University of Medicine COVID tracker.

In Spokane County, 1,306 residents have died from the virus, and nearly half of these deaths occurred after May 2021, when vaccines were widely available.

For local caregivers, the past two years have been a constant ebb and flow, an overwhelming amount of loss and tragedy tied to the necessity to keep going day by day.

“The impact of repeated loss, I think, has probably been one of the hardest things for our health care workers, and for me in general, you don’t want to become used to it, right?” said Christa Arguinchona, who manages Sacred Heart Medical Center’s special pathogens unit. “And you want to be continually impacted by: We lost another person to this.”

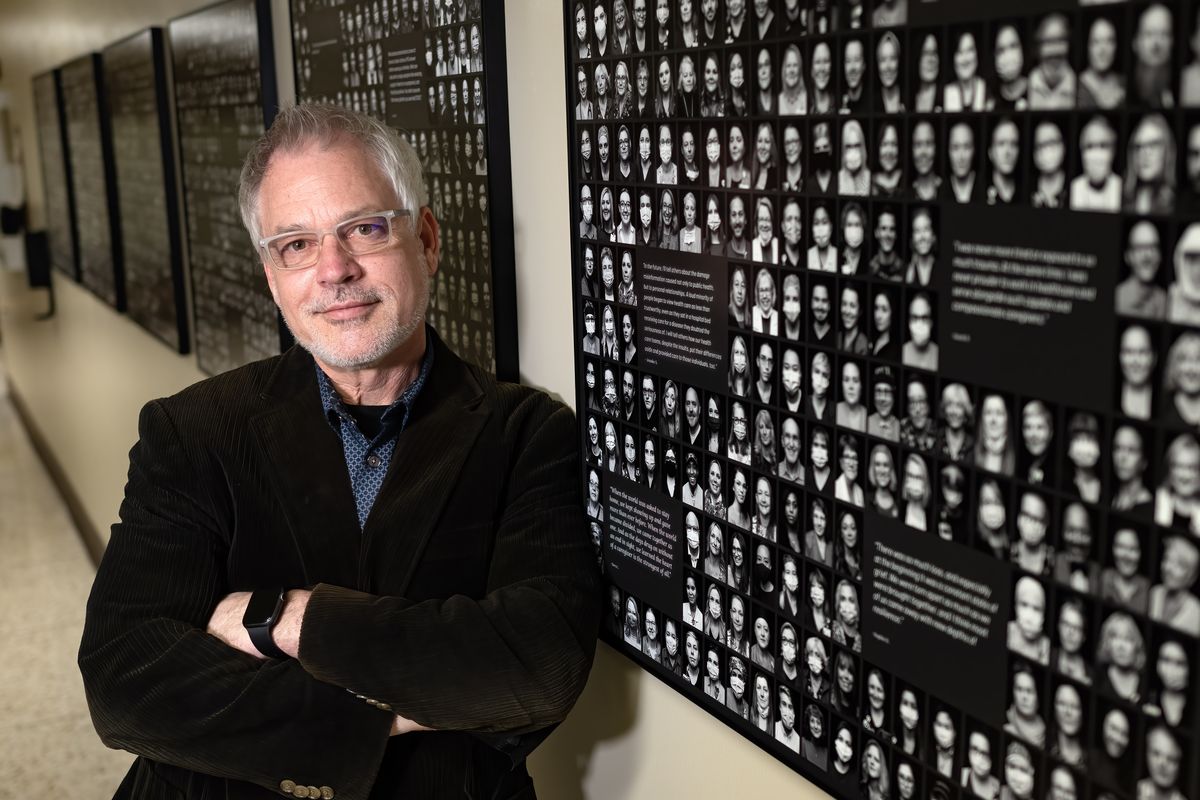

In October 2021, at the height of the delta variant surge, which was the deadliest and most intense wave to date for Spokane County, local photographer Dean Davis captured portraits of 458 caregivers at Providence hospitals in the Inland Northwest.

The resulting black-and-white portraits display the full range of emotions: grief, masks covering half of a person’s face, exhaustion, laughter, a moment to breathe. The condensed portraits now hang in the employee entrance at Sacred Heart Medical Center, a reminder for years to come of what frontline caregivers faced during the pandemic.

Arguinchona said it’s an amazing project to capture a point that will be remembered in history books, much like the Spanish flu pandemic last century.

Sacred Heart Medical Center took care of some of the first passengers who tested positive for the virus during an outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan in February 2020.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quarantined these U.S. residents and shipped four of them to Spokane, home to one of the 10 special pathogens units in the country.

Arguinchona and her team made the unit operational for the first time in its history, treating and taking care of those patients for weeks.

That was early in the pandemic, when health officials were hopeful that they could contain the virus through lengthy quarantines, treating patients at times with experimental drugs. It still was unknown how the virus spread at that point, and health care workers wore full hazmat suits to greet the patients on the tarmac at Fairchild Air Force Base.

Arguinchona recalls the last Diamond Princess passenger being discharged as a high point in the pandemic, and she received a text soon thereafter from him when he reunited with his wife and family. It was the first time the unit had been successfully used to contain and treat infectious patients.

No one knew back in February 2020 what was ahead, and the special pathogens unit would later be used for patient overflow during COVID surges in the coming two years. Arguinchona’s team would be dispersed among COVID floors, sharing their expertise in personal protective equipment and controlling the spread of a virus.

It’s been a team effort for caregivers treating COVID the past two years. Dr. Greg Heinicke, a hospitalist at Sacred Heart Medical Center, saw just about everything, from COVID patients in the clinic to COVID patients on ventilators.

“The toughest part of the pandemic was when resources were tight and the resulting human tragedy was at its highest,” he said.

He credited the dozens of health care workers, from environmental services staff to physicians and respiratory therapists, behind each patient who survived the virus. The perseverance and consistency of health care teams is what enabled that work to continue the past two years.

He said the delta wave was terrible, and teamwork became vital to ensuring that even if someone was having an off day, the rest of the health care team could rally around them.

Seeing patients isolated from family members in their time of illness was difficult for care providers, and they tried to be that bridge between the patient and their loved ones, Arguinchona said.

The resulting fatigue was equally hard.

“This was a different level of fatigue and exhaustion, and that was hard to see,” she said.

As the country and state exhales with the ease of the omicron surge, Heinicke said treatment has gotten much more consistent in the past two years, a welcome comfort for what any future wave might bring.

Still, the weight of what the pandemic has meant for frontline staff remains.

“I have learned the level of human perseverance and human tragedy on levels that I just wasn’t expecting to see in my life,” Heinicke said.