With 10 nurses pregnant and 2 new mothers, Holy Family Hospital maternity staff defies pandemic ‘baby bust’

Peyton Johnson is a month away from being a first-time mother, but she’s well prepared to have a newborn.

For one thing, she works the night shift.

For another, that shift is spent in the labor-and-delivery unit of Providence Holy Family Hospital on Spokane’s north side.

Johnson won’t be alone in gaining some first-hand experience in her unit’s line of work.

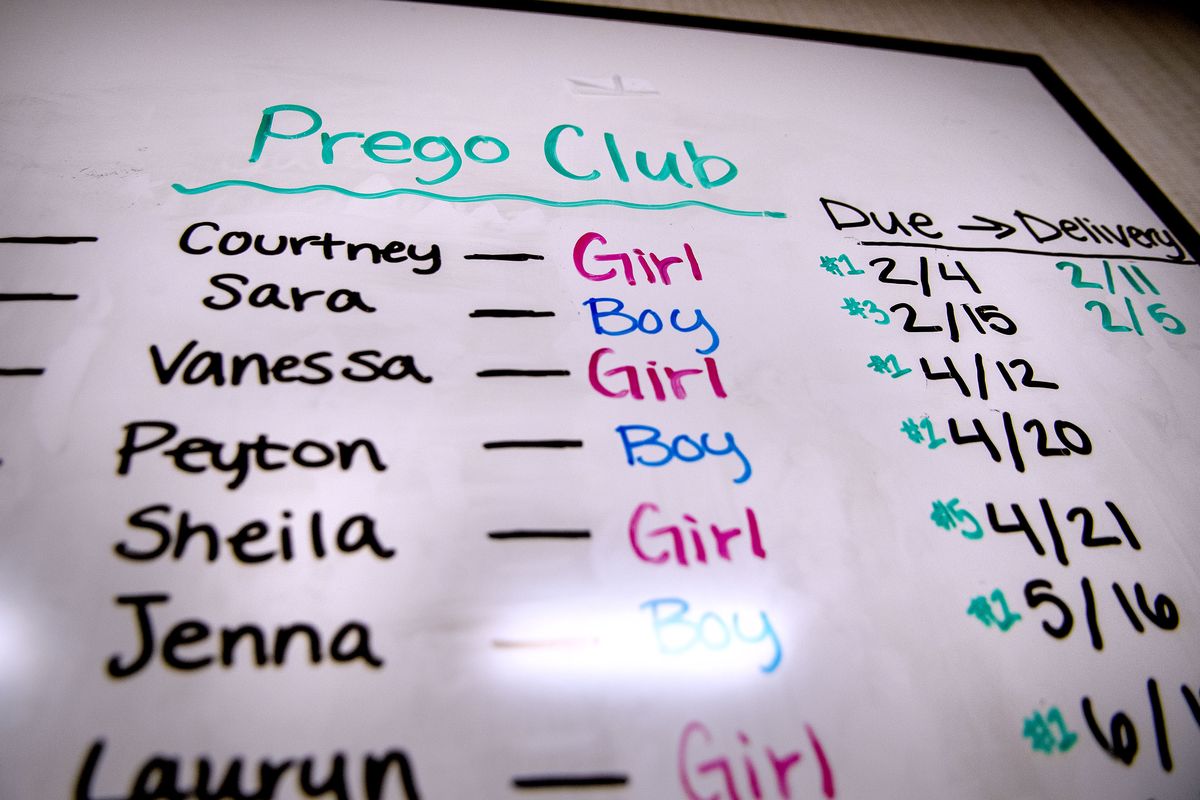

She is just one of a dozen Holy Family labor-and-delivery nurses who recently gave birth or will soon.

On a unit with 54 nurses, that means nearly a quarter of the nursing staff are, or are on the brink of being, new mothers.

But that midpandemic baby boom contradicts the broader trend, according to Deanna Higgins, the unit’s nursing manager.

She said Holy Family has seen a decline in deliveries since COVID-19 hit.

The same thing has happened nationwide.

According to the Brookings Institution, the U.S. will likely see a “baby bust” of 300,000 fewer births this year due to both the public health crisis and the ensuing economic downturn.

Johnson noted that some evidence suggests even some women who have become pregnant during the pandemic have decided to give birth at home due to a general sense that it “can be scary to come to a hospital during this time.”

But it may be more than perception that’s driving down birth rates. Recent studies suggest that pregnant women are at greater risk of contracting – and dying from – COVID-19.

Pandemic or not, Johnson acknowledged that giving birth can always “be a little scary,” even for someone who works in that environment for a living. And she also recognized those fears have been elevated for many “during this time.”

It has also led to changes in how women deliver, with expectant mothers only allowed one support person to be with them before, during and after labor.

That means nurses like Johnson have often had to step in take over the roles that family and friends usually play. She said she and her fellow nurses snap photos, hold phones for FaceTime chats and otherwise have taken on new roles with patients.

For Johnson and the 11 others, though, the line between friend, family and nurse can blend, she said.

She thinks of her co-workers as family – and some of those unofficial “sisters” will be with her when she gives birth alongside her husband.

As for whether COVID caused her any worries, she said that “it never crossed my mind” that COVID posed the kind of danger that would have made her want to avoid pregnancy.

In fact, she said, it has been “a bright spot … in a stressful year.”

All of the pregnancies have, however, caused some stress for Higgins, the nurse manager.

While she said her staff’s pregnancies have offered “a chance to smile” – or a dozen chances – it also led her to wonder, “Do we need extra staff?”

Ultimately, though, she’s confident the pregnancies will be timed in such a way that her unit is able to made do.

“They’re all stretched out, as far as their delivery dates,” Higgins said.

Or almost all of them.

Johnson said she and another nurse have delivery dates one day apart.