Ammon Bundy arrested in Boise after missing his trial on trespass charges

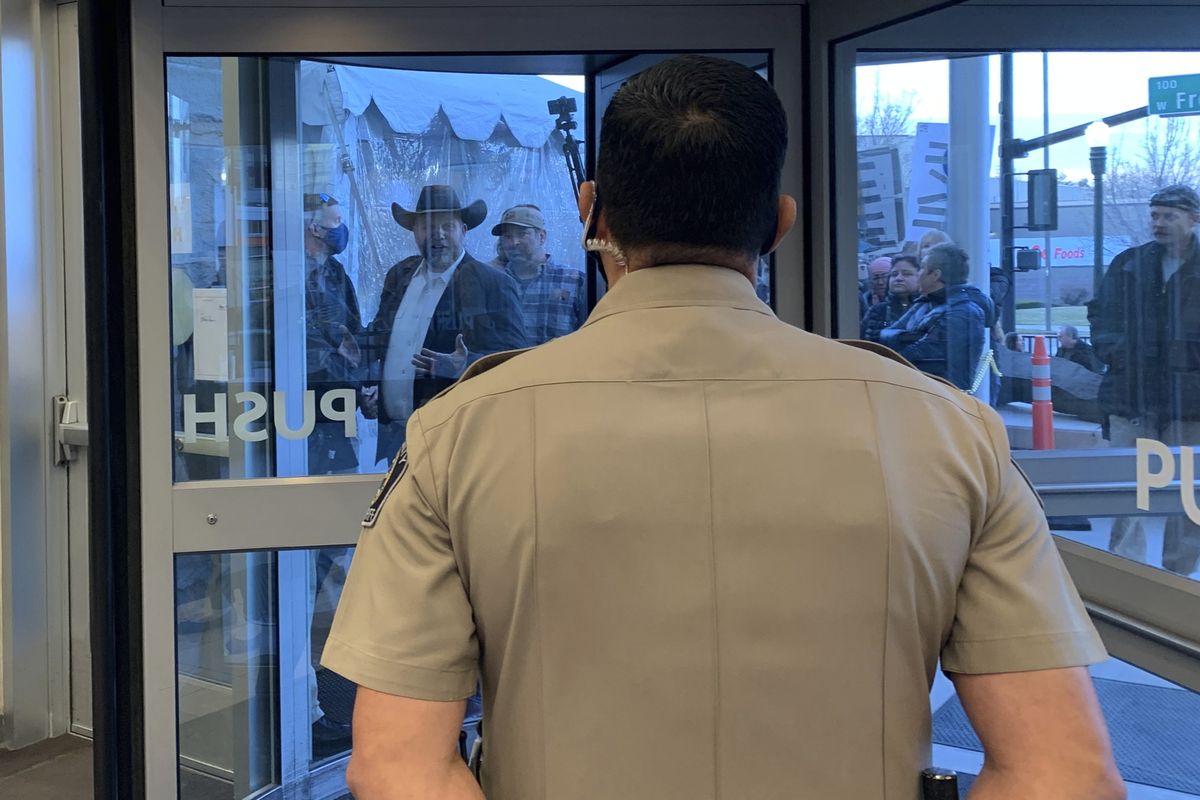

Anti-government activist Ammon Bundy, wearing a cowboy hat, yells through the closed Ada County Courthouse door at law enforcement officers on Monday in Boise. Bundy, 45, was angry about the court’s mask requirements. (Rebecca Boone)

BOISE – Anti-government activist Ammon Bundy was arrested Monday after failing to attend his trial on charges that he trespassed during an Idaho legislative session last fall. Bundy didn’t appear in the courtroom because he was protesting outside the building instead, apparently angry in part over mask requirements put in place during the coronavirus pandemic.

Bundy was joined by about two dozen other protesters on Monday morning, some holding signs with slogans like “Ammon stands for truth” and others yelling misinformation and conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic popularized by groups like QAnon. Bundy and followers of his “People’s Rights” organization have frequently protested coronavirus-related measures in southwestern Idaho since the pandemic began, including the protests at the Statehouse last August that originally led to Bundy’s arrest on trespassing charges.

In one of the August protests, angry, unmasked protesters forced their way into a House gallery with limited seating, shattering a glass door in the process. The next day, more than 100 protesters shouted down and forced from the room lawmakers on a committee considering a bill to shield businesses and government agencies from coronavirus-related liability. Bundy was arrested for trespassing when he wouldn’t leave the room, and again the next day when he returned to the Statehouse despite a one-year ban.

Bundy is representing himself in his criminal case. Shortly after his August arrests, he told Judge David Manweiler that he doesn’t believe his actions at the Idaho Statehouse were illegal, and he claims the state doesn’t have legal standing to charge him with a crime.

He also filed subpoenas – legal orders to testify or turn over documents – to several bystanders and officials who were at the Idaho Statehouse during his arrests, including Associated Press reporter Keith Ridler, who photographed and reported on the incidents.

The AP asked Manweiler to reject the subpoena for Ridler’s testimony and his reporting materials in part because the news agency said the subpoena would violate the “Idaho’s Reporter’s Privilege,” a legal balancing act that courts take to determine if a subpoena given to a member of the news media would chill their First Amendment rights.

Bundy didn’t respond to the AP’s motion.

On Monday, Manweiler said Bundy failed to show that the subpoena would have met the three prongs of the reporter’s privilege test: that there is probable cause to believe the reporter had some information that was clearly relevant to a specific violation of the law, that the information can’t be found in another way, and that there was a compelling and overriding interest in the information that would have justified potentially limiting Ridler’s First Amendment rights.

“Subpoenas to members of the media are particularly onerous because they threaten to intrude into the newsgathering process,” the AP’s attorneys wrote in their motion to the court. “Being forced to testify or produce evidence in a court case also threatens the independence of a free press and potentially puts journalists at personal risk. It risks causing Ridler to be viewed as aligned with one party or the other, potentially impacting how the public will perceive the independence of his reporting, and could even make him a target the next time he covers a public event.”

Bundy drew international attention when in 2016 he led a group of armed activists in the occupation of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to protest the federal control of public lands. He and others were ultimately arrested, ending the 41-day occupation. But Bundy was acquitted of all federal charges in that case by an Oregon jury.

In 2014, Bundy, several brothers and his father led an armed standoff in Nevada with Bureau of Land Management agents who attempted to confiscate his father’s cattle for grazing on public land without a permit.

He spent almost two years in federal custody before the judge later declared a mistrial.