Community Health Monitoring Program connects and comforts patients in the midst of COVID-19

Jeremy Taylor, a volunteer with the Community Health Monitoring Program, holds a pulse oximeter and a care package of supplies the organization delivers to people who test positive for COVID-19. (Tyler Tjomsland/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

Katie Haney jumped at the opportunity to help in any way she could when COVID-19 first arrived in came to the Inland Northwest in March.

She volunteered to be a part of the Community Health Monitoring Program, organized by the Spokane Alliance, to help support residents who contracted COVID-19.

When health district investigators call a person who has tested positive for the novel coronavirus, they can refer that person to the program. If a person chooses to participate, volunteers are matched with a patient to call for at least 10 days after their diagnosis. Patients are supplied with information about the virus and get a pulse oximeter delivered to their doorstep.

Haney did the online training, learning how to call patients regularly and refer them to a medical provider when necessary.

But then she got COVID-19 herself.

Haney, who is 70 and retired, opted to be a part of the program she was trained to volunteer for. She had a pulse oximeter delivered to her doorstep by volunteers and received a call from a volunteer every day for 10 days.

Pulse oximeters, which typically clip to the end of a person’s finger, measure the amount of oxygen in one’s blood. If those levels dip too low, it could be a sign that a person needs more oxygen or supplemental oxygen, and should go to the hospital.

“It was great,” Haney said. “It was right at the outset (of the pandemic). It was a very scary thing for people over the age of 70, so having that monitor at the house gave me a sense of confidence that I wasn’t deteriorating.”

Haney suspects that she got the virus from her husband, who eventually tested positive after doctors ruled out what they thought was bronchitis. Haney said her husband likely contracted it when they attended the West Coast Conference basketball tournament in Las Vegas in early March. Masks were not required or recommended at that point.

Haney’s symptoms never became too severe. She had a fever and a scratchy throat. She felt weak and achy for a few days, but never fell too ill. Her husband’s illness was more severe, she said, but neither of them needed to go to the hospital.

Haney was thankful to have a volunteer check in with her on a daily basis while she was ill, and she looks forward to being able to help someone else if she’s called on to volunteer in the future.

“It’s another way for people who have the disease and are isolated – and should be isolated – to have outside contact and encouragement,” she said. “The volunteers are able to encourage and be supportive and give them positive suggestions and all that stuff, so it’s kind of twofold.”

Chloe Sciammas and Ivan Jimenez, both recent graduates of Gonzaga University, are leading the Community Health Monitoring Program.

For Sciammas, one of her final classes in her last semester at Gonzaga led her to her new role leading the program. The idea for the program came as a hopeful solution to the question: How can we alleviate the stress on hospitals? If people could monitor their oxygen levels and heart rates, they could know when they need more medical attention or are just fine at home.

Washington State University received a grant from Innovia to obtain 1,000 pulse oximeters for the program, and Sciammas and leaders from the Spokane Alliance made connections with the Spokane Regional Health District to enable referrals into the program.

The goal, Sciammas said, was to get patients “the medical information they need to feel competent in their healing if their symptoms are improving, or if they are on the verge of not being OK.”

Sciammas and the initial team recruited about 300 volunteers to train. Jimenez graduated last year from Gonzaga and has been working on community organizing since then.

He was supposed to be going into the Peace Corps in April, but the pandemic closed that door quickly. He joined Sciammas in organizing the program in April.

When a person opts into the program, they are assigned a volunteer who could have up to three patients to call on a daily basis for at least 10 days after that person has tested positive. A separate team of volunteers does deliveries and pickups of the pulse oximeters to patients for the program.

If a patient is worried about these levels, the program has a medical provider on call to talk to patients, advising them on whether or not they should seek additional care.

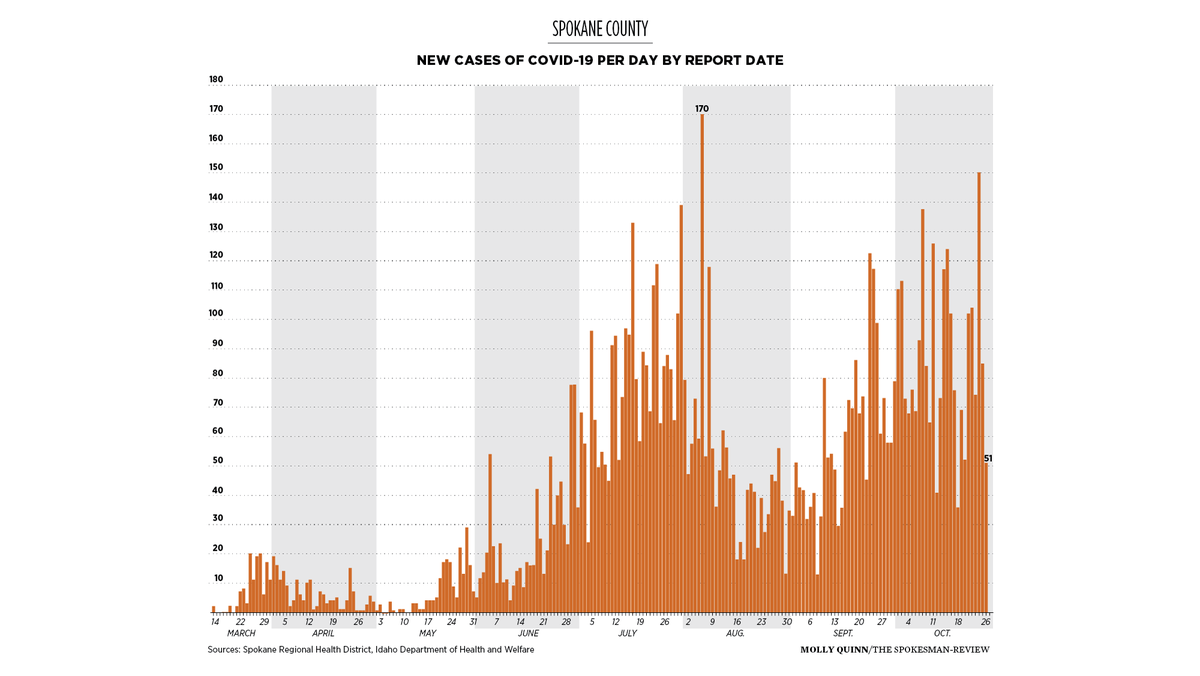

Referrals seemed to trickle in and have continued throughout the pandemic.

However, the program isn’t used nearly as much as organizers expected. As of Oct. 23, 111 people have participated in the program.

“We think it’s a combination of people being more comfortable and so many other levels of organizations working on this,” Jimenez said.

The Spokane Regional Health District is required to offer care coordination, as a part of the state’s COVID response dictates, which could be why fewer people are opting into the program.

The Community Health Monitoring Program offers specific services that could be limiting who they can serve, said Kelli Hawkins, public information officer at the district. The state health department offers care coordination as well.

Additionally, demand could be down due to the demographics of who is testing positive. Young people testing positive might not need daily monitoring. In Spokane County, 20- and 30-year-olds make up 40% of COVID-19 cases.

There are still several volunteers who have yet to be assigned patients, although the program will continue to exist as long as it is needed and as long as the grant funding continues.

The program is funded through a $25,000 grant from Innovia . The funding will last through the end of the year, and then the Alliance will re-evaluate whether the program can continue.

Since March, the program has expanded beyond Spokane.

Fernanda Mascota, who is an organizer with Raiz, a Planned Parenthood program that works in the Latinx community to bridge the gap in health care access, is promoting the Community Health Monitoring program to her clients when her group goes out and does COVID-19 testing in parts of Central Washington.

For a couple of months, Mascota and her team have been offering free drive-up COVID-19 testing in Central Washington, focusing on farm working communities.

Mascota works with some patients who speak Spanish, and she is able to coordinate their care with volunteers that also speak Spanish. Since May, Mascota has been able to expand the program to a broader community, so they can be supported, especially those without access to health care in the traditional sense.

“We are going to expand and go all over the place, and what I do is take the monitors and enroll folks as they need it,” she said.

Mascota takes pulse oximeters with her when they host COVID-19 testing clinics from Yakima to Wenatchee, and she plans to continue to coordinate these services, especially for people who do not have established medical providers.

“A lot of them don’t speak English or are uninsured and are at home and scared, so they are so grateful that someone calls them every day to see how they are doing,” she said.