What happens if a presidential candidate withdraws or dies close to an election? The law isn’t quite clear

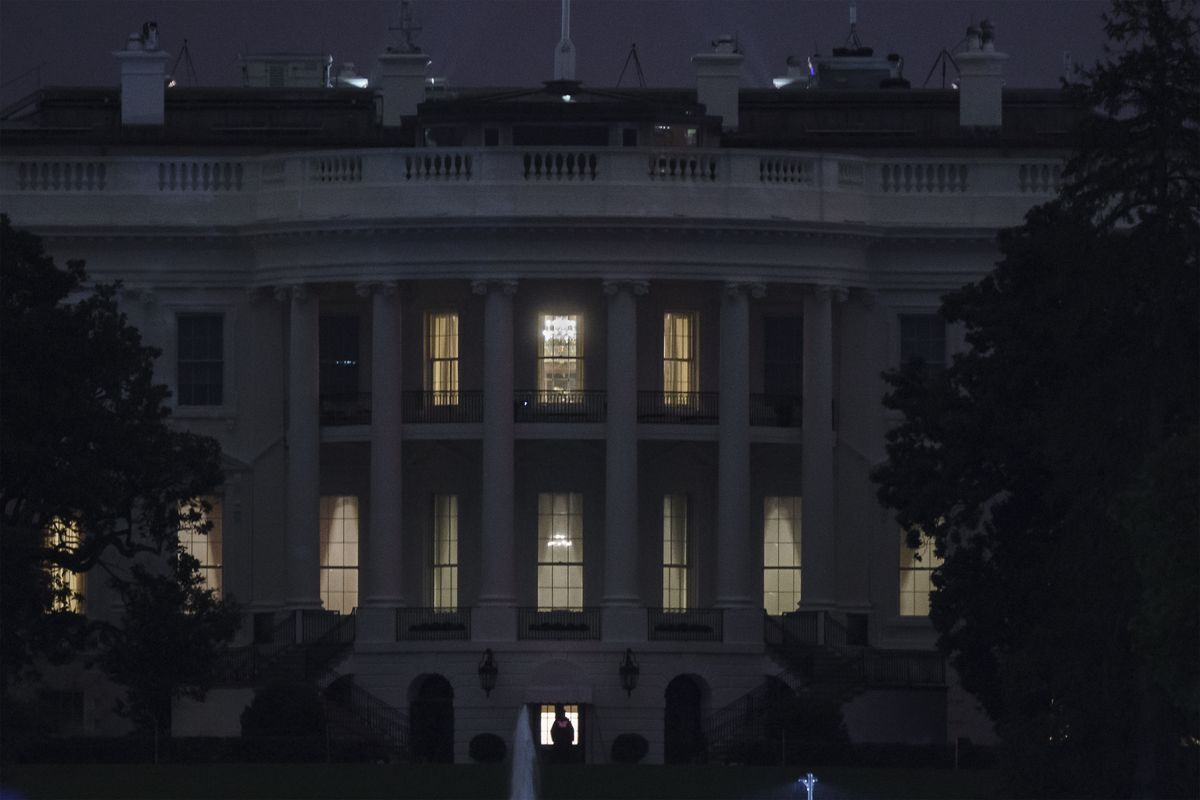

The White House is seen on Oct. 2, 2020 after President Donald Trump announced that he and first lady Melania Trump tested positive for the coronavirus. (J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

President Donald Trump’s recent COVID-19 diagnosis has brought on questions about what happens when a president becomes too ill to work.

The Constitution has pretty clear guidance on what to do if a president becomes incapacitated or dies while in office, as laid out in the 25th Amendment.

But it gets trickier if a presidential candidate becomes seriously ill close to an election.

Even before Trump’s diagnosis, rules for succession during elections were receiving added attention because of the age of the top candidates. Trump is 74. Democratic nominee Joe Biden is 77.

It’s unclear what effect the diagnosis will have on the election, said Cornell Clayton, the director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University. A total of eight U.S. presidents have died in office, four of natural causes and four by the hand of an assassin. None of them became ill or were killed so close to an election day.

The issue isn’t clearly addressed in the Constitution or any federal law, said Richard Seamon, a University of Idaho law professor .

“There are a lot of unanswered questions,” Seamon said.

A few scenarios could play out, if that happens.

If a president become incapacitated while in office

The 25th Amendment lays out two options if a president becomes too sick while in office: voluntary or involuntary.

If the president chooses to step aside, he will submit a written declaration to the Senate and the House of Representatives, saying he is unable to perform the functions of his office. The power then goes to the vice president. If the president becomes well enough to take over, he will submit another written declaration to the House and Senate.

George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan both voluntarily used the 25th amendment in order to undergo medical procedures.

If a president does not voluntarily step aside, the vice president and cabinet level heads submit a declaration to the House and the Senate. When a majority agrees, the vice president takes over.

If a president remains too ill to perform his duties or dies, the vice president takes over throughout the remaining term.

If a presidential candidate becomes incapacitated before an election

There’s a clear line of succession laid out in federal law if a president becomes incapacitated before an election, Clayton said.

“I don’t think there’s any problem about who’s going to be in charge,” Clayton said. “We know that; there’s a process for that.”

However, with only a month until Election Day, this would be slightly more difficult.

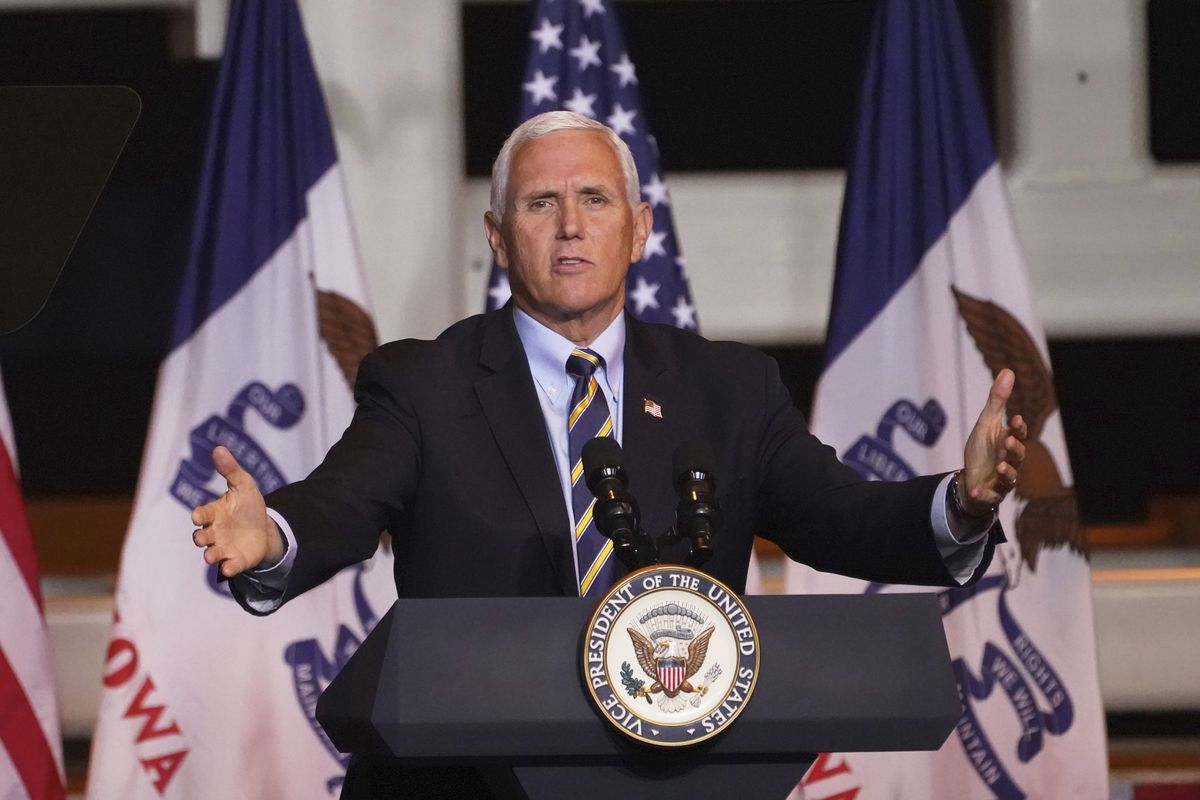

The Republican National Committee would be responsible for nominating another candidate if that should happen before Nov. 3. The committee’s 168 members would vote on the leadership’s recommendation for a replacement.

The RNC and the Democratic National Committee have their own set of rules for how they nominate their candidates, said Benjamin Cover, associate professor at University of Idaho College of Law.

Because they are independent bodies, their rules are not listed in any federal or state law.

The problem this close to the election would be getting that person’s name on the ballot, Clayton said, since many states are already beginning early voting during the pandemic.

Trump will almost certainly be on the ballot in November regardless of his health and regardless of a replacement Republican nominee, leading to the next scenario.

If a presidential candidate becomes incapacitated after an election but before the Electoral College votes

Because the United States has the Electoral College, citizens vote for their electors, not necessarily their presidential candidate, Cover said.

Each state appoints their electors and has different rules for what their electors can do.

The 538 electors will meet on Dec. 14 in their states to record their votes, which must be received by the President of the Senate and the Archivist no later than Dec. 23.

If a candidate becomes incapacitated before the Electoral College, the candidate’s political party would come up with a replacement, and electors would most likely want to support whomever their political party chooses, Cover said.

“The electors are usually members of the political party who are very committed to the party, have a great deal of experience and loyalty,” Cover said.

But it gets slightly more complicated.

The constitution does not require electors to follow the state’s popular vote, but most states’ laws do.

The Supreme Court ruled in July in Chiafalo v. Washington in June that a state has the ability to require electors to vote with the state’s popular vote. Previous Washington state law fined electors if they did not follow the state’s popular vote. However, electors who choose not to follow the state vote are now replaced with an alternate. Idaho has no punishment for faithless electors.

In states where electors are not legally bound to choose the popular vote winner, electors would most likely vote for the new candidate their party has chosen as a replacement. In states where electors are legally bound to the popular vote winner, there is often no guidance for what to do if a candidate becomes incapacitated.

The Chiafalo decision did have a footnote about what might happen if a nominee dies, Cover said, but did not make it clear what the responsibilities of the electors would be.

Most likely, if a nominee dies, electors would be released from their original pledge, Cover said, but it is still unclear.

If the party could not determine a new candidate, the vote might be split in the Electoral College with no real winner. The 12th Amendment lays out the process if no candidates receive a majority of electoral votes – at least 270. At that point, the House of Representatives would select the president, voting by state with each state having one vote. That process was last used to select a president after the election of 1824.

Still, the laws surrounding this scenario are unclear and often rest on the states, as there isn’t much federal law about it, Cover said.

“The federal Constitution says nothing about this because it’s up to the state to decide how they choose electors,” Cover said.

If a presidential candidate becomes incapacitated after the Electoral College, but before the inauguration

If a candidate is elected to president, voted on by the Electoral College and finalized by Congress, but then becomes incapacitated, the 20th Amendment comes into play.

The 20th Amendment, which determines term length for a president, describes the process for what happens if a president-elect dies before assuming office. The current president’s term ends at noon on Jan. 20, but if the president-elect dies before then, the vice president-elect will be sworn in as president.

The amendment only accounts for a president-elect’s death, Cover said. If a president-elect is too sick, most likely he would be sworn in as president and then enact the 25th Amendment, allowing the vice president to take over.

Spokesman-Review reporter Kip Hill contributed to this report.