After 6 months and little progress controlling the pandemic, return to normal remains out of sight

(Molly Quinn / The Spokesman-Review)

It’s been nearly half a year since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in the United States, in the Puget Sound area, on Jan. 21.

While the state eventually shut down in late March in an effort to slow the disease’s spread, Washington began the gradual process of reopening after little more than a month.

But as counties began moving through the stages of the state’s phased reopening plan, the coronavirus was just beginning its wider spread outside the Seattle area and into other parts of the state, including to Yakima, the Tri-Cities and, eventually, Spokane.

Since April, after a particularly bad first wave in Western Washington, Central and Eastern Washington have been hit with their own first waves of the virus, leading to newly reopened restaurants shutting down all over again, to outbreaks in prison units and food processing plants, and to community spread, even in rural counties.

Case rates statewide are higher now, with half the counties partially reopened, than they were in April, and state public health officials have paused any further reopening for now.

In Spokane, hospitalizations have doubled in a month, and intensive care capacity remains a concern due to questions about staffing levels.

In Yakima, where Gov. Jay Inslee’s masking orders first went into effect , patients were sent to hospitals outside the area when staff needs hit capacity.

Franklin County has the highest percent-positive rate in the state, with 32% of individuals tested in the last two weeks returning positive results.

Six months into the pandemic, it feels like not a lot has changed.

Test results are backed up again, with people having to wait a week to 10 days in isolation to see if they are positive or negative. Community spread, when the virus is contracted without known connections to other cases, is back on the rise, as it was in March and April.

The rising number of cases has put increased challenges and pressure on contact tracing efforts, which began with reopening and are now incredibly strained and overwhelmed.

Despite the state training hundreds of workers and National Guard members to do contact tracing, counties like Spokane have opted to hire outside companies to conduct contact tracing. With more than 460 cases confirmed this week alone, the work has eclipsed what local epidemiologists can handle.

The ripple effect

Washington was on lockdown from late March to early May, giving public health officials and state leaders an opportunity to prepare outbreaks underway and on the way, predominantly in long-term care facilities across the state and more broadly in the Puget Sound area.

By May, residents were antsy, and reopening lurched forward, with Ins-lee’s phased plan taking effect.

Despite state leaders’ efforts to ensure counties were ready to move ahead, it’s apparent now they miscalculated in some cases. Some counties hadn’t had their first wave yet.

According to Eric Lofgren, an epidemiologist at Washington State University, some took the absence of cases in some areas as evidence the virus had been safely contained. In reality, he said, the first wave hadn’t fully reached parts of Eastern Washington, including Spokane and the Tri-Cities.

“If you don’t have cases, that means either your epidemic hasn’t started yet or you’ve successfully controlled it,” Lofgren said. “So I think everyone said we successfully controlled it, and what we discovered was that in several states we discovered that your epidemic was a little slower in coming.”

The same story played out across the country in states that reopened this summer after seeing relatively low case counts – but are now seeing hospitalizations and case counts surge.

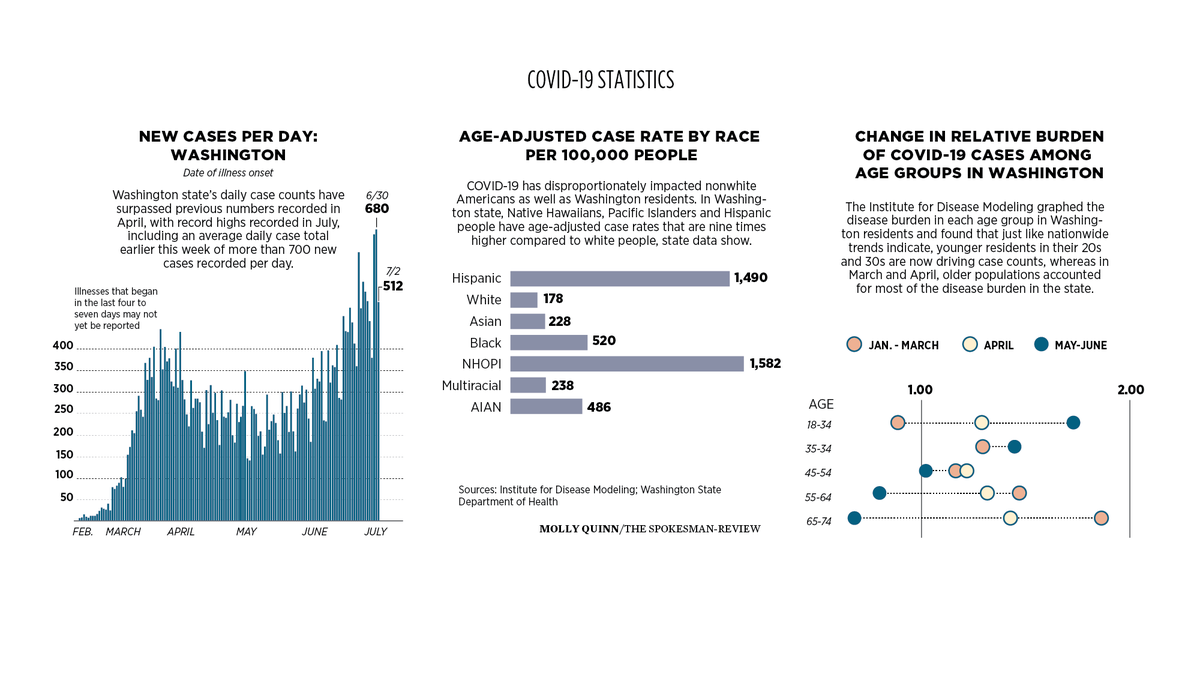

Washington is now seeing higher daily case counts in July than April.

Testing capacity is back to waits of 10 days to two weeks for results , largely due to rising demand and growing backlogs at national laboratories, where the majority of the country’s testing capacity lies.

“We are truly back to where we were in March,” Spokane County Health Officer Bob Lutz said Friday, noting the challenges felt in Spokane are felt statewide and nationally .

Long wait times make it challenging for public health officials asking people to isolate at home until they get test results.

“Delays are harmful because they don’t allow us to quickly contain a case,” Secretary of Health John Wiesman told reporters Thursday. “We know people are most infectious early on … and that’s why we say to anybody getting a test that if you have any reason to get a test, we want you to stay home until you get your results.”

With more testing, came more cases, but that doesn’t paint the full picture of the disease burden.

The statewide percent-positive rate has also steadily increased this summer, as has the rate of people testing positive in counties per 100,000 people. Only 16 counties statewide are meeting case rate goals set by the governor’s Safe Start plan.

Could more have been done during the state’s lockdown to prevent the COVID-19 resurgence? Lofgren thinks so.

“I think at both a national and local level, what happened is we did sort of waste the opportunities we had to get things in place for people to start taking this seriously, to put testing strategies in place,” he said.

The state’s positive rate is back up to nearly 6%, and modelers are now confident the epidemic was growing in both Eastern and Western Washington in mid- to late June.

“While the resurgence in cases was originally limited to a few hot spots, upward trends are now prominent in most counties,” the most recent state modeling report says.

Summer is nearly half over, and schools are set to open in less than two months. With so much of the response feeling like déjà vu, health officials lament the lost time.

“We had breathing room, and we’ve largely used it on politicizing the epidemic,” Lofgren said.

Finding a treatment

In half a year, treatment options for COVID-19 have improved, but doctors and researchers are still far from a treatment that works even half the time on patients who are hospitalized with the virus.

Two standout treatments, remdesivir and dexamethasone, appear to have some positive results, although the studies are ongoing and results are still preliminary in both clinical trials.

A study from a large drug trial led by Oxford University researchers found that dexamethasone, a common steroid, was helpful in treating patients with COVID-19 who were on oxygen or ventilated. While their study has not yet been peer-reviewed or published, their early results look somewhat promising. The steroid kept one person in a group of 20 with severe symptoms from dying .

These results are impressive in the drug trial world, but they have a long way to go before proving entirely useful.

Both MultiCare and Providence hospitals have enrolled in the clinical trials for remdesivir guided by the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Henry Arguinchona, an infectious disease practitioner at Sacred Heart Medical Center, said initial trials of the drug also look promising.

Patients receiving remdesivir in the trial are faring better than those who get the placebo. The trial will soon move into its third phase; second phase results are forthcoming.

Early in the pandemic, ventilators were an in-demand lifesaving tool . While they are still being used for some patients, physicians are not immediately putting patients on them anymore. The National Institutes of Health now recommends a less invasive intervention – a high-flow nasal cannula – over a ventilator in some instances.

Some patients are doing well and able to get more oxygen to their lungs when they are simply flipped onto their stomachs, Arguinchona said, another technique doctors, nurses and intensivists are using.

“I feel that we know better now how to take care of these patients, but I am hopeful that one or two or three or four months now, we know even more,” Arguinchona said.

Recovering from COVID-19 is far from a linear process, and some people have experienced ongoing symptoms or side effects of their body’s fight with the virus for months. As The Atlantic’s Ed Yong notes, some people with COVID-19 and ongoing illness call themselves “long-haulers.” Yong writes that they are “navigating a landscape of uncertainty and fear with a map whose landmarks don’t reflect their surroundings.”

Arguinchona said the phenomenon of patients not getting better is being seen more and more in COVID patients, but he noted that lingering health conditions are not necessarily indicative of persisting virus in the person.

“There are many infections a person can get, and afterwards they can get a postinfectious syndrome,” Arguinchona said. “They can be left with lingering symptoms. With regards to post-COVID-19 symptoms, it’s not known what the causes or etymology of those is.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers a patient who is not admitted to the hospital with the virus as having a mild case, but Lofgren notes that “mild” doesn’t really give weight to potential symptoms and conditions patients experience.

“There are a lot of people who had supposedly mild cases of COVID who are still struggling with lung function and struggling with cardiovascular issues,” Lofgren said.

Who is impacted by COVID-19

The virus has exposed the inequities that already run rampant throughout the American health care system, including here in Washington.

When adjusted for population size, Hispanics and Pacific Islanders have nine times the number of COVID-19 cases than white people in Washington. The disproportionate rates of the virus trickle into hospitalizations and deaths from the virus , and nonwhite communities are hit hard by the virus statewide.

In Spokane County, the Marshallese community has experienced devastating effects of the virus.

“The pandemic has exacerbated the underlying and persistent inequities among historically marginalized communities and those disproportionately impacted due to structural racism and other forms of systemic oppression,” a July 8 report from the Department of Health says.

The department allotted a half-million dollars to get community organizations funding to bolster virus prevention and response efforts in a large swath of communities statewide. DOH awarded dozens of community organizations contracts that ranged from $5,000 to $20,000 to fund communication and emergency outreach services for communities that are disproportionately impacted by the virus.

Some pregnant women are also not faring well if they contract COVID-19. A CDC report found that pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to be hospitalized and are at increased risk for ICU admission than nonpregnant women. Nationwide, 11,312 pregnant women have contracted the virus, and 31 of them have died.

Arguinchona said some pregnant women have become very ill with COVID.

Young people, who were not as impacted at the beginning of the pandemic, are now driving case counts locally, statewide and nationally.

Twenty- and 30-somethings make up 38% of confirmed COVID-19 cases statewide and 45% of cases in Spokane County.

In recent weeks, health officials have pleaded with young people to stop gathering in large groups and to wear masks when around one another. Most young people might experience mild symptoms with the virus, but the fear is that they will bring the virus to their older parents or grandparents, or spread the virus when they are at work.

“We have a lot of work to do with younger folks here in Washington limiting their social interactions and make sure they’re wearing masks,” State Health Officer Kathy Lofy told reporters on July 8.

Back to school?

With the start of the school year less than two months away, community members and public health officials remain skeptical that kids will be back in their classrooms.

Dr. David Line, the public health program director at Eastern Washington University, says the county will “pay for our actions,” including July 4 gatherings with case counts and hospitalizations.

At the end of the first wave, if enough of the community has started wearing masks and adhering to small gathering requirements, it should be doing well, he said.

“If we aren’t doing well at the end of (the next) seven weeks, if we don’t have a low caseload, we are in really big trouble because that’s when school starts,” Line said. “… If we miss that window that occurs right now through the rest of the summer, we will not be able to contain that wildfire at least through all next school year.”

Wearing masks and face coverings could determine what school districts do when school begins.

Lofgren has studied how schools can stay open and avoid transmission of infectious disease.

“It’s possible … we can have school, but it’s not as fun as it used to be,” he said. “It’s possible we can’t get a 5-year-old to wear a mask, but we can get an 8-year-old to wear a mask.”

Measures such as not allowing group activities such as band and choir, having teachers instead of students move from classroom to classroom, and having students eat in the classroom, could help minimize widespread interaction of students in schools.

Schools might use hybrid models of partial reopening , depending on the district and the county’s phase of reopening . The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction wants schools to reopen in-person but officials acknowledge districts in Phase 1 or modified Phase 1 counties might have to implement additional safety measures.

DOH guidance for schools requires universal masking but leaves additional measures at the discretion of school districts.

As for colleges, research indicates congregate living settings like dorms are perfect breeding grounds for virus transmission.

A group of college students from the University of Texas who went to Cabo San Lucas for spring break in March ended up in a perfect COVID environment. Three symptomatic students were tested when they returned, and the contact tracing investigation revealed 64 total people had contracted the virus.

Shared housing both on-campus and during their spring break trip led researchers to believe that patterns of living and interacting in close settings could lead to “propagated spread, similar to the continued person-to-person transmission observed in long-term care facilities.”

‘The better part of a year’

As Washington and other states experience a surge in cases this month, health officials insist widespread mask use is key to bringing down transmission rates in the near future.

For EWU’s Line, it comes down to community buy-in on masking and cooperation with contact tracing efforts.

“We could do nothing and let the whole thing burn up. We could do this fake open-close thing and suffer the whole way through. Or we can do some pretty simple things and get full support by everybody and not have to suffer and be fine in seven to eight weeks,” he said.

The Department of Health and the CDC recommended the use of face coverings in early April, but mandates took longer. Leaders hoped residents would take the advice and wear face coverings, in place of hunkering down at home. That didn’t work.

In mid-May, some local jurisdictions, including King and Spokane counties, mandated masks, though the mandates weren’t always enforced.

Statewide, however, masks were not required for all residents until late June. That requirement is likely to remain in place for a long time.

“Wear a mask, social distance, try to take responsibility for your own part of this outbreak, and that means things aren’t going to be fun for a while and that’s hard, but those sacrifices mean maybe kids can go to school, maybe those stressed households are less stressed,” Lofgren said.

The notion that we will be “done” with COVID-19 soon is not realistic, Lofgren said.

“We need to start engaging with the idea that this isn’t a couple months,” he said. “It’s the better part of the year.”

Researchers and health care providers are working overtime around the country and the world to find out just how effective and long-lasting antibodies are, and how effective a vaccine could be as a result.

“We’re not promised a treatment or a vaccine,” Lofgren said.