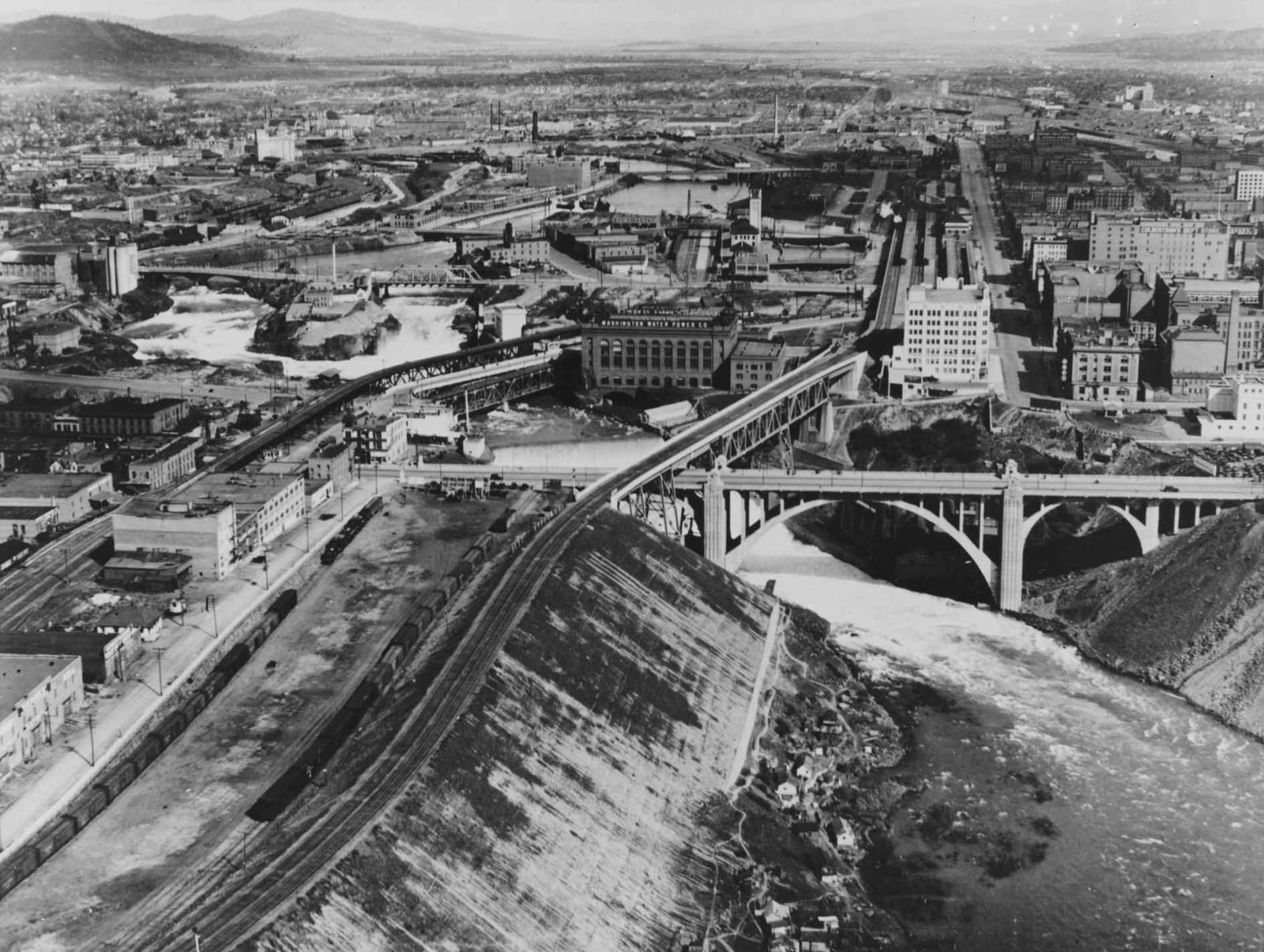

Aerial view of the Spokane River

One of the biggest changes to the downtown waterfront was the removal of the rails. In the 1960s, city boosters began to dream of a world’s fair around the falls in Spokane. And one of the biggest roadblocks was the tangle of steel rails that snaked across Havermale Island and along the shore of the river. The railroads had carried passengers and freight through town for almost a century, but now organizer King Cole and Spokane Unlimited Inc. saw the dingy rail yards and aged depots as a visual blight on the scenic waterway.

Section:Then & Now

Image One

Photo Archive

| The Spokesman-Review

Image Two

Jesse Tinsley

| The Spokesman-Review

One of the biggest changes to the downtown waterfront was the removal of the rails.

In the 1960s, city boosters began to dream of a world’s fair around the falls in Spokane. And one of the biggest roadblocks was the tangle of steel rails that snaked across Havermale Island and along the shore of the river. The railroads had carried passengers and freight through town for almost a century, but now organizer King Cole and Spokane Unlimited Inc. saw the dingy rail yards and aged depots as a visual blight on the scenic waterway. They needed the railroads to consolidate their yard operations outside the downtown core and combine the traffic onto tracks four blocks to the south, then donate their land to the city. There was no money to buy the land. Four railroads stood in the way: The Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, the Union Pacific and the Chicago Milwaukee. The GN merged with the NP to become Burlington Northern in 1970, and agreed to consolidate, but organizers needed to speed up their timeline. But the UP and Milwaukee were more stubborn. They had multiple lanes of elevated tracks beside the Union Depot on Trent, now Spokane Falls Blvd. Pressure came from organizers, the city, business interests and shippers who used the rails. Historian William Youngs tells the story in his book “The Fair and the Falls” and reveals that the railroads capitulated after many sensitive negotiations involving complex land deals and contracts. The city even gave the 13th green at Indian Canyon golf course to the Northern Pacific so the track, curving northwest from the Latah Creek bridge, could pass overhead. Between 1971 and 1973, tracks were torn up, depots and trestles torn down and the waterfront remade. An Associated Press story from April 1974 said “Expo ’74 is stubbornly succeeding. It’s organizers think the fair and the city have something to offer the nation and world. If nothing else, it has rekindle the spirit of Spokane.”

Share on Social Media