Then and Now: Wheeler's Barber Shop

The barber shop in the Peyton Building became the center of Civil Rights controversy in 1963 when John W. Wheeler refused to cut the hair of a Liberian college student.

Section:Then & Now

Then and Now: Wheeler's Barber Shop

In the early 1960s, America was watching Southern states dealing with firebomb attacks against Civil Rights leaders, violent street protests, fights over school integration and access to lunch counters. The historic March on Washington took place in 1963. But Spokane seemed to be left out of these historic events, though a small news item in October put the city in the national spotlight.

Barber John W. Wheeler was a fixture in downtown Spokane, having bought a shop in the Peyton Building in 1918 and expanded it to several employees with multiple chairs. The shop had a shoeshine stand staffed by Black employees, but he refused to cut Black folks' hair. Wheeler and his wife, Ida, had two sons killed in World War II.

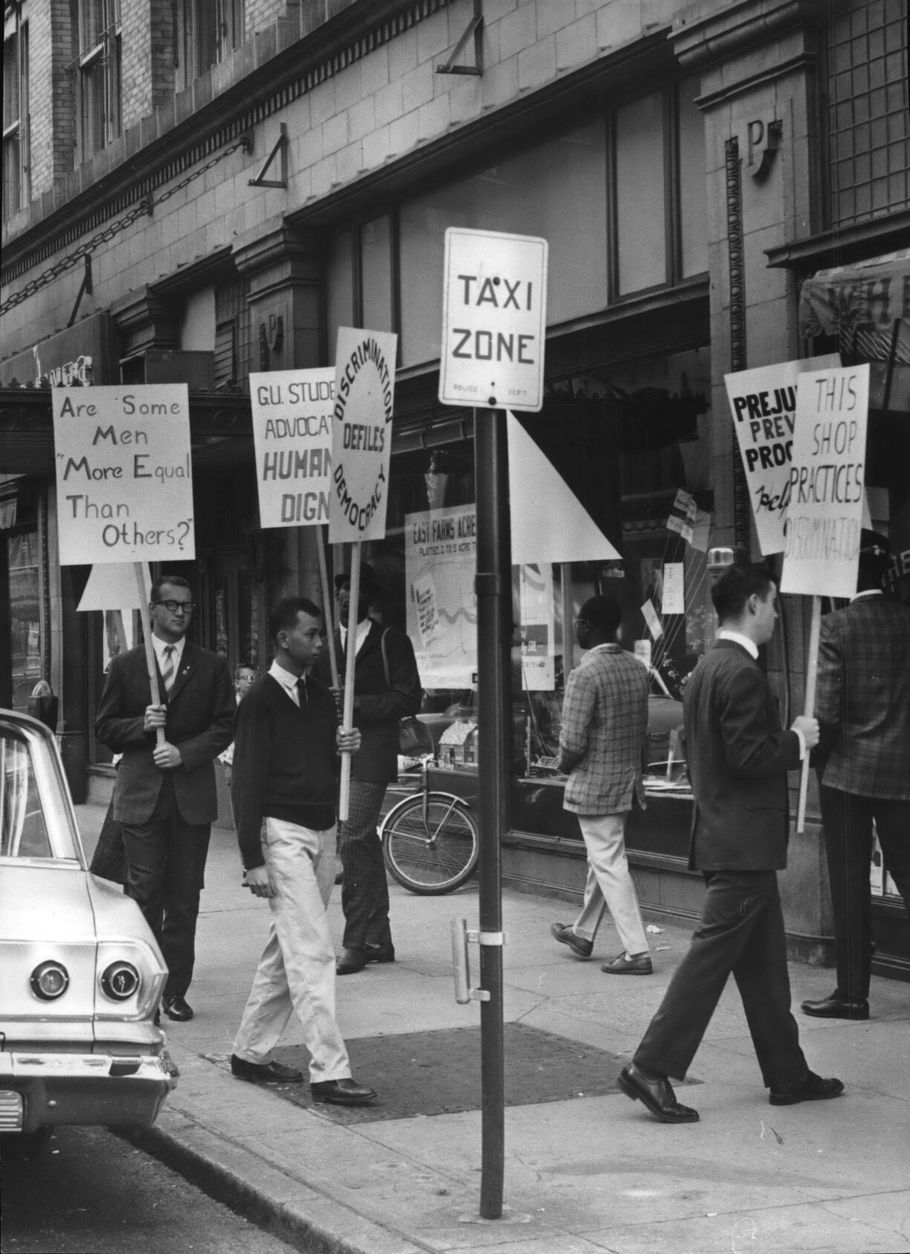

In October 1963, a college student from Liberia, Jangaba “Gus” Johnson, went to Wheeler’s shop and the owner told him he didn’t cut “colored hair.” Johnson left the shop, but that wasn’t the end of it. Johnson told his classmates and a protest began to build. On Saturday, Oct. 19, 1964, some 35 students showed up with picket signs. The protest showed up on CBS News, and a story ran on the Chicago Tribune front page.

Attorney Carl Maxey filed a complaint with the Washington State Board Against Discrimination. Former Spokesman-Review writer and columnist Jim Kershner tells the story in his 2008 book “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life.”

Wheeler was unrepentant about his refusal of service, saying “you cannot mix trade in the barbershop and keep your customers." That echoed what many Spokane business owners had claimed over the years. Though little had been codified in city or county law, Black citizens had been excluded from many Spokane restaurants and social clubs by signs that read “No colored patronage solicited.” African-Americans knew the few places in Spokane where they would be served.

Maxey spoke before the Board of Discrimination. “The eyes of the world are on Spokane and on a small barber shop. But the issue is not small," he said. "We face the decision of whether a man with a public license can say on is own, ‘I cannot or I will not serve you.’”

The board took less than three minutes to rule against Wheeler, who appealed the ruling to the State Supreme Court. In 1967, the high court denied Wheeler’s petition. Rather than comply, the barber closed his shop and retired. He died in 1974.

Share on Social Media