John Green’s brand is optimism. On book tour, he’s fighting despair.

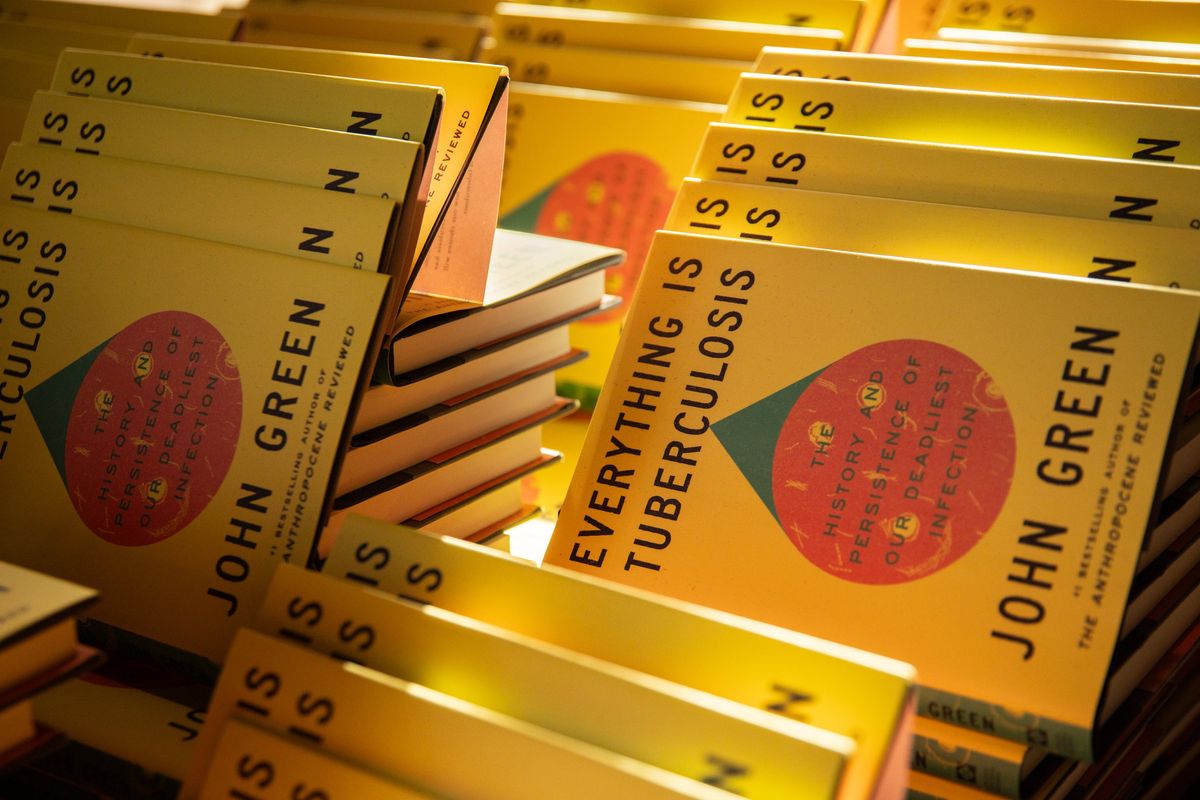

Green signs books March 19 ahead of his sold-out talk in Washington, D.C. (Maansi Srivastava/For the Washington Post)

Some people get tennis elbow; John Green has bestseller shoulder. His doctor said – no joke – that Green, 47, was developing arthritis from signing so many books: more than 700,000, he estimates, over the past 10 years. For his latest, Green signed more than 100,000 sheets of paper, to be bound into copies from the first printing. When we met at the D.C. stop of his tour, he was looking at – what, another thousand? “Easy peasy,” he said. He propped his phone against a stack of hardcovers to take a time-lapse video for his socials, and uncapped his Sharpie.

Green, best known as the author of “The Fault in Our Stars,” hoped that all this signing would help draw readers to the new book. It’s a sharp turn from the novels that made him a touchstone for sensitive teens. “Everything Is Tuberculosis” tells the real-life story of Henry Reider, a young poet battling drug-resistant TB, whom Green befriended during a trip to Sierra Leone. It also tours the history of one of humanity’s oldest contagious diseases and probes why – despite the existence of effective treatments – it remains the most fatal.

And the book is just the start: “I don’t want people to think that this is the culmination of my interest in tuberculosis. I didn’t, like, get really interested in bats, and now I’m going to get real interested in … mice,” Green said. On his right wrist, he wore a TB-themed friendship bracelet, hand-beaded by a fan. “This is the work of my life now.”

When Green finished writing the book, “I really felt like we were at a moment of inflection with tuberculosis,” he said. A good new vaccine candidate had emerged. Cheaper diagnostics – crucially, ones that would work reliably for children – were on the cusp of becoming available. More attention would come to the disease, and with it, more resources. Green pictured his advocacy as part of that process, nudging the flywheel forward.

And now? “Now I feel like we are on the edge of the cliff. And, in fact, that we have chosen to step over the cliff.”

He remembers the precise moment when President Donald Trump issued the executive order freezing nearly all foreign aid, with the aim of closing the U.S. Agency for International Development entirely. Green was at his son’s birthday party when texts started coming in: from friends who worked in public health programs; from friends who relied on such programs to access lifesaving medication. The next day, Green sat down to record the audiobook for “Everything Is Tuberculosis.”

As he read, he thought about the next chapter now being written by American politicians. He knew that hundreds of thousands of people would lose access to their treatment in the middle of their regimens. He knew that if they couldn’t access treatment, they would die; even if they could resume treatment, they were likely to develop drug resistance.

“It was surreal. It was terrifying. It still is terrifying. I can’t get my head around that kind of punitive cruelty,” he said.

Green’s public persona, mixing Muppety consternation with faith in the world’s goodness, helped define millennial twee. Its appeal has proved remarkably durable, from the vlog he and his brother, Hank, started in the early 2000s to their current incarnation as, they quip, “vertical video sensations.” (Between their CrashCourse and vlogbrothers channels, they have more than 20 million YouTube subscribers; on TikTok, John Green has another 2.8 million.) Green ported that style over to his TB advocacy: Even when calling on corporations to lower the costs of drugs and tests, the moral urgency was generously salted with nerd whimsy. In one recurring bit, viewers threw out a random topic – Oppenheimer, women’s shoes, his dog Potato – and he connected it to tuberculosis. Fans look to the Greens not just for entertainment or education, but also for comfort.

Sitting in the green room just before he went onstage, his face was drawn. This was the most press he had ever done, an absolute blitz of TV and radio: the CBS evening and morning programs, “Amanpour & Company,” “Morning Joe.” “I would give anything for my book to be less timely,” he kept saying. Earlier, he’d met with USAID staffers; the conversation, he said simply, was “difficult.” These days, many were. In briefings he got from health workers, which were “usually quite dry,” people had been breaking down in tears.

“Ultimately, the legislative branch is going to have to do its job,” he said, unblinking. “Which is not just true for USAID – it’s also true across the board. The legislative branch is going to have to claim the power that is given to it in the Constitution, the power of the purse.”

After the book launch winds down, in April, Green will return to Washington, where he and other advocates will lobby lawmakers on Capitol Hill. The terrain of their fight has shifted tectonically. In the past, the system to detect, treat and prevent tuberculosis may have been frustratingly under-resourced – but it existed, and that bare fact represented America’s commitment to the ideal of global health. Now it has collapsed.

“I’m very discouraged,” Green said. (“Encouraged,” he writes in the book, is a word that Henry Reider particularly loves: “Who wouldn’t? Encouraged, like courage is something we rouse ourselves and others into.”)

“I’m deeply afraid,” he continued, borrowing a line from Auden: “But I also feel more determined than ever to use whatever voice I have to undo the folded lie.” The poem later continues: “There is no such thing as the State/ And no one exists alone.”

I asked Green whether he ever felt pressured to be optimistic. He let out a startling burst of laughter – AHAHAHA! – as if it were lettered all-caps, in a speech bubble above his head.

“That’s a great question, man. Because it’s my brand, you mean?” Green paused. “Well, yeah. But I also think – young people are, with very good reason, very prone to despair. And I am very prone to despair. I have to fight despair every day. For me, hope is not some abstract concept. It is a prerequisite for my survival. And so I don’t have room for hopelessness in my life. I’ve got to fight it. I’ve got to fight it everywhere I can. Because my life kind of depends on it.”

Perhaps one, small cause for hope: Nearly all the events on his cross-country tour were sold out. That night, when Green went onstage, it resembled nothing so much as a secular prayer service. He read aloud from a shared text. He gave a homily of sorts, about how though we may all feel we are living at the end of history, we are living in the middle, and it falls to us to fight for a better outcome. He even led the room in collective song, “a battle cry for hope,” to the tune of “Auld Lang Syne”: “We’re here because we’re here, because we’re here, because we’re here.”

The next morning, on his way out of town, Green ducked into the Hudson News at Union Station. He signed four more copies of the book.