Judges side with hunters in corner crossing case, but issue remains unsettled in Washington, Idaho

A hunter follows his English setter near Hells Canyon in Idaho in this 2023 file photo. (Michael Wright/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

Public land access advocates were thrilled this week when a panel of federal judges sided with hunters in a trespassing suit that centered on the legality of “corner crossing” as a way to reach public land that is otherwise blocked.

The ruling by a three-judge panel in the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed a lawsuit filed by a Wyoming landowner against four hunters from Missouri who twice hunted public land surrounded by a private ranch.

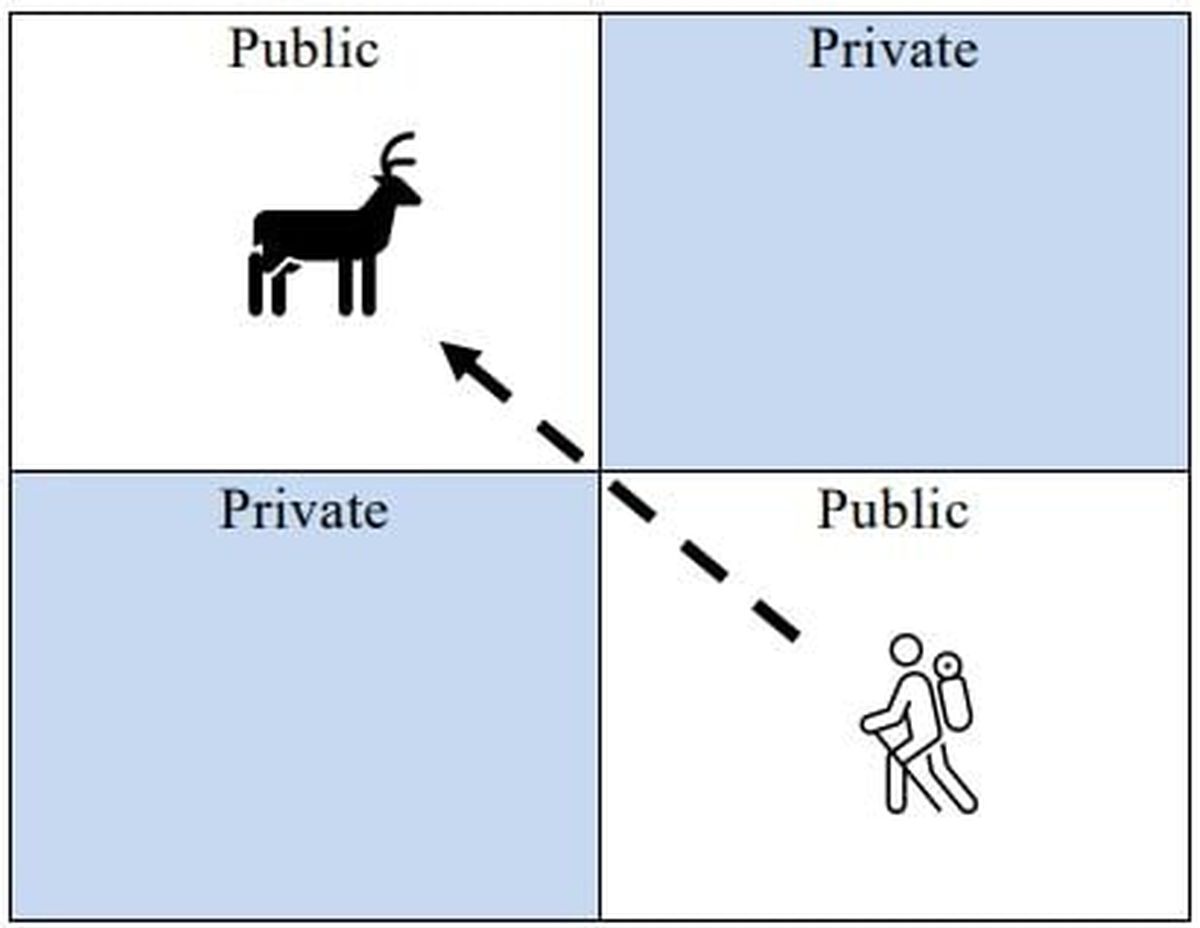

At issue was whether they trespassed while moving diagonally between public parcels adjoined at the corners but otherwise surrounded by private land.

The y never set foot on the private land, but the landowner argued that the hunters entered the airspace over the private land, and that doing so constituted trespassing.

Not so, the judges ruled unanimously on Tuesday, siding with the hunters and affirming a lower court’s decision to dismiss the case.

The ruling, which provides a comprehensive history lesson on the problem of checkerboard landownership, cited the 1885 Unlawful Inclosures Act, which prohibits landowners from putting up barriers to otherwise accessible public lands.

In this case, it means a landowner can’t “implement a program which has the effect of ‘deny(ing) access to (federal) public lands for lawful purposes,’ ” the judges wrote.

Access advocates are celebrating the ruling as a groundbreaking win that means corner crossing is legal in the 10th Circuit states – Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Utah – that means corner crossing is legal.

Outside those six states, however, the legality of corner crossing remains unclear.

Devin O’Dea, the western policy and conservation manager for Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, said in states outside the 10th Circuit the ruling is “persuasive” and could help bolster the case for corner crossing, but isn’t legally binding.

“This could be interpreted on a case -by -case basis,” O’Dea said. “That’s not to say it’s illegal. It’s still a gray area.”

Staci Lehman, a spokesperson for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, said trespassing is illegal, but that Washington has no laws that explicitly prohibit midair crossings or “crossing property boundaries where two corners come together.”

Ditto for Idaho. Roger Phillips, an Idaho Department of Fish and Game spokesman, said there’s no legal precedent in either federal or state court that provides any clarity.

“The legality, or illegality, of corner crossing is not a settled legal issue in Idaho,” Phillips said in an email.

Settling the question would have a major impact for hunters and other public land users across the West, where more than 8 million public acres are accessible only through corner crossing, according to a report produced by onX Maps.

Washington has 125,000 acres of corner-locked land, while Idaho has 57,000 acres. Wyoming has the largest share of corner-locked property, with 2.44 million acres.

It all traces back to the 1800s, when the federal government used land grants to encourage the construction of a transcontinental railroad. Government officials drew 6-mile-by-6-mile townships within a certain distance of a proposed railroad route, then divided those squares into 36 square-mile sections.

Sections were numbered. Odd sections were given to railroad companies and the federal government held onto the even sections, creating a pattern that looks exactly like a checkerboard.

Through a series of homesteading acts, settlers claimed portions of the federal government’s sections. Railroad companies also sold some of their land.

Unspool that for several decades and you get the complex patchwork that exists today, with public land managed by agencies like the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service interspersed with private.

Conflicts arose over access to public lands even in the 1800s, according to the ruling from the 10th Circuit. Competition for pasture lands was intense, and illegal fencing was a significant problem.

That led to Congress passing the Unlawful Inclosures Act. The judges wrote this week that the law was “designed to harmonize public access to the public domain with adjacent private landholdings.” The ruling quotes a section of the law that bars landowners from using “force, threats, intimidation or by any fencing or inclosing” to keep people from entering or settling on public lands.

In the Wyoming case, the four hunters from Missouri were hunting BLM land in Carbon County, west of Cheyenne. The corner they crossed was surrounded by the Elk Mountain Ranch, owned by pharmaceutical executive Fred Eshelman’s Iron Bar Holdings.

The ranch covers about 50 square miles. Interspersed throughout is about 11,000 acres of public land.

The corner the hunters crossed was marked with a U.S. Geological Survey stake. A photo included in the ruling shows the stake, which sits between a pair of T-Posts put up by staff of the Elk Mountain Ranch, with “No Trespassing” signs attached to them.

The hunters – Bradley Cape, Zachary Smith, Phillip Yeomans and John Slowensky – were there in 2020 and 2021, and they crossed at the corner both times.

The first year, the ruling says, they swung around them, ensuring their feet never touched private property. The next year, they brought a ladder.

Ranch staff had a history of confronting suspected trespassers, even if they were on public land. They confronted the Missouri both times but got more aggressive in 2021. They urged the local prosecutor to bring trespassing charges. They claimed the hunters had trespassed over their private airspace.

A jury acquitted the hunters, but Eshelmen filed a civil trespassing suit immediately after the verdict. A lower court dismissed the case, and Eshelman appealed to the 10th Circuit.

Attorneys for Eshelman had argued that the Unlawful Inclosure Act applied only to physical fences. The judges rejected that argument, citing the portion of the law that refers to threats and intimidation.

The judges wrote that means “no one can completely prevent or obstruct one another from peacefully entering or freely passing over or through public lands.”

O’Dea, of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, which raised more than $200,000 to fund the hunters’ defense, said it’s possible the landowner will seek to take the case further, perhaps by petitioning the Supreme Court.

But he’s also hopeful it might restart conrer crossing conversations in statehouses. Outside of taking simple trespassing cases as far as they can go, state legislatures are the venue where the issue can be settled.

Bills have been introduced in states like Montana, but none has passed.

Bills that would deem corner crossing legal have been introduced in state legislatures, but none have passed.

“Now that there’s this big decision, we’ll probably see a lot more interest in kind of addressing the issue on the state level,” O’Dea said.