How Sun Valley built the racecourse for the FIS Ski World Cup Finals

During a January course tour, Riley Berman, chief of course for the FIS Ski World Cup Finals in Sun Valley, Idaho, walks past towers his team installed to hold up the netting that protects ski racers who may crash. (Gregory Scruggs/The Seattle Times)

SUN VALLEY, Idaho – A foot of fresh snow makes skiers rejoice. But for Riley Berman, chief of course for the FIS Ski World Cup Finals at Sun Valley Resort, a powder day isn’t dreamy – it’s a nightmare.

That’s because some 800 people – 145 of the world’s top racers, plus their team entourages, officials and media – have flown into Idaho’s Wood River Valley (population: 25,000) for the biggest alpine race outside the Winter Olympics.

Many of these people have traveled to Idaho from Europe, where the World Cup ( which runs through Thursday) typically finishes along the constellation of racecourses that dot the Alps, Pyrenees and Nordic countries. But for the first time in nearly a decade, the elite ski racing circuit has returned to North America for the grand finale on a new course that could re-establish Sun Valley as a world-class race venue – which means the pressure is on for the hosts.

“If it gets pulled off and we race all the events, this is going to be huge for not only getting more World Cup events in the U.S., but just ski racing in general over here,” said U.S. Ski & Snowboard coach Austin Savaria via phone last week from Sun Valley, as two of his racers took practice runs.

With 19 inches of new snowfall since March 13, resort guests have enjoyed the powder with every turn across Bald Mountain. But Berman and his crew of over 100 have been working frantically day and night to clear the new snowfall from Challenger, the racecourse they have painstakingly modified and enhanced for the World Cup in a truncated time.

The course has been closed to the public since March 6 – when Berman’s team began installing safety netting and watering the slopes to transform a series of runs used by thousands of local skiers daily into a carefully manicured, uniform surface that meets the strict standards set by ski racing’s governing body, the International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS), to ensure fair competition.

So when nearly a foot of snow fell overnight last week, it became an all-hands-on-deck operation. Berman’s core team of 30 swelled threefold and spread out to roll up safety netting and shovel snow by hand off the course. While his counterparts at marquee races in Austria and Switzerland quite literally have national armies at their disposal, Berman has relied on help from resort staff and volunteers.

Skilled groomers operate a dozen snowcats to plow the snow open like a farmer’s field so that crew members can direct industrial-strength hoses onto the 1.5-mile course. A combination of snowcats driving slowly and course crew stepping down the mountain sideways on their skis generates friction, which brings the water to the surface. The water hardens in the cold, making for compact snow almost the consistency of ice – the average skier’s bête noire, and the ski racer’s ideal surface.

It’s all part of the herculean behind-the-scenes effort that goes into building what Berman – handpicked for the job due to his unique background and skill set – proudly calls “the Super Bowl of ski courses.”

‘The obvious guy’

The son of a ski shop owner, Berman grew up in the Wood River Valley and competed as a junior racer with the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation.

On race days, Berman dreamed of shaping a course as much as skiing it. “The fun part for me is constructing the playground,” he said, while touring a reporter around the under-construction Challenger Course in January as 28 newly installed snowmaking guns roared overhead.

Berman, 33, has long demonstrated a predilection for hard work and grueling days. He lives on a plot of land with donkeys, horses, pigs, goats, chickens, cats and dogs. Come dinnertime, he and his wife pull hunks of elk they’ve harvested themselves out of the freezer. In his senior year of high school, Berman organized a 21-day expedition by snowmobile, touring skis, kayak and raft to travel 425 miles along the Salmon and Snake rivers during spring runoff, when the rivers threw Class V whitewater rapids at him. After college in Colorado, he returned home and became a summertime fishing guide and wintertime manager for Rotarun, a nonprofit community ski hill that couldn’t be more different from glitzy Sun Valley up the road.

As mountain manager for five years, Berman oversaw the installation of six state-of-the-art snowmaking guns and kick-started more advanced grooming that’s proving essential to Rotarun’s viability as an affordable alternative to Sun Valley. In his spare time, Berman also pitched in as a course crew member during major races.

Last year, Sun Valley tapped him for the World Cup job on the basis of his transformative work at Rotarun, which entailed many of the skills he would need to build out Challenger.

“He was the obvious guy,” said Savaria, a childhood friend and fellow racer. “There’s not really anyone else here living in the valley that would have the knowledge and the drive and want to do it.”

Berman had been at work for three months when Sun Valley formally announced in late September that it was hosting the finals. The offseason provides a precious window to move dirt and take down trees before the first snowfall complicates things. “One of the things that was really challenging was we weren’t able to start until July 1,” Berman said at a Ketchum public library talk in January. That meant nine months total, while World Cup hosts typically have two to three years to prepare.

“After the summer inspections, conducted by FIS and the organizers, several adjustments were made to optimize the course for World Cup racing and ensure safety, including the installation of safety nets and other infrastructure,” wrote FIS spokesperson Giulia Candiago via email. “A project like this is feasible within a six-month time frame because it did not require building a course from scratch.”

Even though Sun Valley did not build a new course from virgin mountainside, turning existing runs into a World Cup course is still a serious undertaking for any ski resort, according to Stevens Pass general manager Ellen Galbraith, who served as chief of course for the 2015 Women’s Alpine Ski Championship downhill in Beaver Creek, Colorado, and who advised Berman on crew selection over the last year.

“It is so much work and time, plus a huge amount of resources,” Galbraith said. “Putting on races of this level is a massive commitment.”

Anatomy of a racecourse

At its core, a racecourse is not that different from a ski run – it’s a human-made route down a snow-covered mountain created by removing trees and moving dirt around. The best ski runs ideally follow the fall line, or gravity’s path downhill on a slope. Twists and turns along the slope’s natural contour add challenge and excitement. A bank allows a skier to take a turn faster, while a dip might launch them into the air. All these features are magnified on a racecourse, where skiers are flying fast. That means widening a run to allow more room for a racer’s big arcing turns or packing down dirt to a consistent grade so there’s a sufficient landing zone after a jump that rockets a racer into the air.

Elite ski racing courses are a dime-a-dozen in Europe, where most of the World Cup circuit takes place, but only a handful of North American resorts have put on races of this caliber. Sun Valley last hosted a World Cup event in 1977 – and the Northwest hasn’t seen racing on this level since the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver and Whistler, British Columbia. (Crystal Mountain hosted a World Cup race in 1972 and Red Mountain in Rossland, British Columbia, hosted in 1968.)

But putting Challenger together on an accelerated schedule was no mean feat. With only a few months before first snowfall, the hill was a flurry of activity – from tree removal at the start of the downhill course to moving 7,000 cubic yards of dirt to flatten out the finish line.

Earthwork was accompanied by extensive technical infrastructure to meet World Cup standards. Ski racing measures competitors down to the hundredth of a second using copper timing wires stationed along the course. When Berman and his team started, they only had three working timing wires out of a necessary 100. In addition to digging trenches for the timing wires, Berman’s team also dug 11 larger trenches for pipes to accommodate fiber optic cables for live TV broadcasts.

Next came the racers’ safety netting, a necessary precaution in a sport with an alarming injury rate. Berman’s team erected 72 towers to provide support for the “A-net,” which has a suspension system to guard against crashes in high-risk areas. They also deployed an additional 480 rolls of secondary B-net along the course.

The netting, Berman explained, “is a vertical trampoline – it’s the last defense so the athletes don’t go flying off and hit a tree.”

From top to bottom

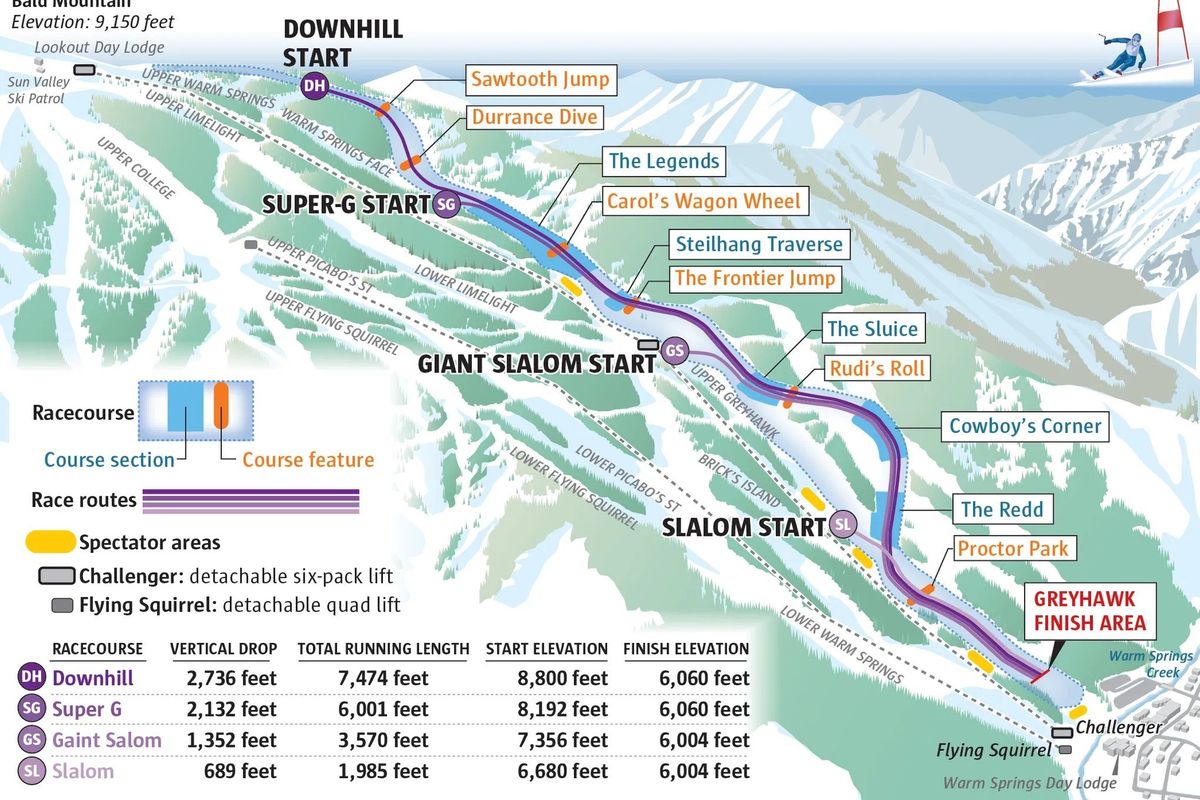

FIS sets minimum and maximum course lengths for the different ski racing disciplines, each of which will use a portion of the Challenger Course. The shortest run is the slalom, covering 689 vertical feet and 700 yards, where racers make tight turns weaving around gates. Then comes giant slalom, which nearly doubles to 1,352 vertical feet. It’s faster than regular slalom with fewer gates. Those two “technical events” favor turning skill over raw power, and are Mikaela Shiffrin’s specialty.

Speed demons such as Lindsey Vonn gravitate toward the Super-G, which in Sun Valley covers 2,132 vertical feet in just over a mile. Finally, the downhill (in which Vonn won Olympic gold at Whistler) tackles the full course running 2,736 vertical feet over 1.5 miles. Covering the most distance, downhill racers are the fastest of the bunch – a World Cup racer has broken 100 mph.

While Sun Valley hosted the U.S. Alpine National Championships in 2023 and 2024 on lower sections of the Challenger Course, the full top-to-bottom run spruced up to World Cup level will see its maiden voyage this week. Racers have inspected the course during training runs, but unlike famed courses such as the Streif in Kitzbuhel, Austria or Birds of Prey in Beaver Creek, Colorado, Sun Valley did not have sufficient preparation time to host a trial event.

“This is going to be the first World Cup Finals where no athlete has skied the downhill before,” said Berman. “This is about as fair and neutral of a ski race as you can get.”

Racecourses are divided into sections and features, like specific jumps or sharp turns, and given names that resonate with local history and folklore. The course’s namesake are the Challenger railroad cars that were known for speed and power. (Sun Valley was founded by the Union Pacific Railroad.) Racers will need plenty of power to maintain speed on this course, which does not have any flat sections for coasting where racers crouch into a tuck – it’s a steep ride from top to bottom.

Fittingly, racers will ride up the Challenger Chairlift to reach the starting line. Now in its second season, Challenger is a six-person rocket ship that Sun Valley Resort claims is the world’s longest chairlift by distance, shooting 3,100 vertical feet in eight minutes. The chairlift remains open to the public during the races, and quite possibly offers the best vantage point onto the racecourse.

Berman’s course crew nearly doubled the width of the existing International black diamond run at the top of the mountain to accommodate the downhill’s starting section. Soon after picking up speed, racers get airborne for the first time. The Sawtooth Jump easily generates some 90 feet of air before racers are forced into a blind landing as the slope falls away underneath their skis. That’s the Durrance Dive, homage to American ski racing pioneer Dick Durrance, who spent part of World War II in Seattle working for Boeing and won Sun Valley’s Harriman Cup three times.

Downhill racers will keep their skis on the ground as they head into the Legends, where the Super-G starts. This section honors Sun Valley’s female champions, starting with Tacoma-born Gretchen Fraser, the first U.S. skier to win Olympic gold. The course then hits a gully called Carol’s Wagon Wheel, named for recently deceased resort owner Carol Holding, and into a short traverse before hitting the course’s signature feature, the Frontier Jump.

“It’s one of the more radical terrain features on the World Cup circuit,” Berman said. “It’s called the Frontier Jump because as you go into that transition, you’re definitely going into the frontier – all you see is blue sky.”

For those who make the landing, there’s room for three big turns before navigating the small ridges and ripples of a section called the Sluice in honor of the region’s mining history. The giant slalom starts just after the Frontier Jump. Next comes a big rollover at Rudi’s Roll, which leads into a sharp right turn called Cowboy Corner. The slalom racers start here, which finishes in a section called the Redd, a reference to salmon and steelhead spawning grounds, where there’s enough pitch for downhillers to reach some 80 mph heading into the finish line.

For Team USA fans, there will be plenty to cheer for. How will Vonn cap off her improbable comeback, coming out of retirement at 40 to race women half her age? Will the sport’s all-time winningest athlete Shiffrin reach the podium on home soil?

Whether you watch from the finish line or tune in on NBC Sports, the Northwest’s original destination ski resort will be on display for the world to see as racers cannonball down the Challenger Course faster than the speed limit on I-5 while toeing the fine line between staying in control and crashing into the nets.

As TV cameras pan across thousands of cheering fans, watch for Berman and his team hustling anonymously in the background to ensure the course is in tiptop shape.

“I don’t know how much Riley has slept in the past year but I bet it’s less than 99% of people,” Savaria said. “When he’s motivated and excited about something, he can put his head down, get lost in the work, and doesn’t struggle with it at all.”