Federal workers ordered back to the office, then told the office is going away

A protest of President Donald Trump and Elon Musk's cuts to the federal government on the National Mall on Feb. 17. (Marvin Joseph/The Washington Post)

Last week, employees of an Agriculture Department office in the South began reporting for full-time in-person work, following President Donald Trump’s directive to end remote and telework arrangements for federal employees.

But in a turn of events that underscores the whiplash effect of Trump administration actions in recent weeks, those employees learned the next day that the government had canceled its lease at the building, effective this spring, as part of another directive meant to improve government efficiency.

“We don’t really know what this means,” said one worker at the office, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. “We can’t telework, but we aren’t going to have an office in a couple of months?”

Across the country, workers who were just ordered back to the office have now learned that their agencies will no longer occupy those buildings, leaving them scrambling to figure out how to honor Trump’s return-to-office mandate with vastly fewer offices.

The mandate has led to a great deal of chaos, even as it continues to roll out, with many employees currently required to report in person and others’ deadlines coming this month. Workers have reported being compelled to kill time in hallways while they wait for their turn at desks in overcapacity offices, while the Federal Emergency Management Agency directed managers to flip a coin to resolve some conflicts over scarce workspaces.

The push by Elon Musk’s U.S. DOGE Service and its allies in the Trump administration to cancel hundreds of leases has only increased the turmoil. Remote workers who have contemplated moving or reorienting their lives around new commutes to report to faraway offices are now being told those office leases are ending. This confusion comes on top of the anxiety wrought by repeated firings of large numbers of employees, as well as a string of lawsuits and court orders that have left many federal workers unsure of whether, and where, they’ll continue to have a job.

Employees of an Interior Department office in the Midwest were likewise required to report for full-time office work beginning Feb. 24. The next day, the landlord of the building walked in and announced that the General Services Administration, which manages federal offices, had canceled the building’s lease, effective late August, said an employee of the office.

“He was kind of stunned,” said the employee, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

The leadership of the office “didn’t know this was happening,” he said. “They didn’t know it was going to happen. Everyone’s under the assumption it came via GSA and via whoever’s pulling GSA’s strings.”

Last week, the GSA launched a “Space Match” program to provide desk space for remote workers returning to the office who don’t live near their own agency’s buildings. Some agencies have begun hosting workers employed by other offices or rolled out plans to do so - only to also be told their leases are now ending.

“We had assumed that our building might be safe because we’re picking up so many remote workers from other agencies that were going to come into our building,” the Interior Department employee said. “We had it laid out, and our building was going to be packed full.”

For some teams, particularly in regional or state offices far from Washington, the government will have to find new office space that won’t just accommodate workers, but also sensitive documents and equipment.

Several agencies have mandates to maintain records for a certain period of time, sometimes indefinitely, requiring extra space for those classified reports, surveys and field studies to be stored.

At the U.S. Geological Survey, leaders in the Oklahoma-Texas region had already been looking in vain for suitable office space for workers and their expensive equipment, said an employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Then, last week, workers in several offices in the region were told their leases were being canceled, the employee said - initially within about 90 days, though the termination date was later extended to May 2026.

“That’s more time, but OKC has been looking for a new office location for the past few years and hasn’t found anywhere suitable as office/storage/warehouse/laboratory all are needed for daily operations,” the employee said via the encrypted messaging app Signal. He said he doesn’t know what will happen to hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of hydrologic equipment that’s used every day.

It’s still unclear just how many leases the administration will cancel. Senior officials have suggested getting rid of as much as 50 percent of federal office space, and a directive last month ordered agencies with offices in the D.C. region to submit plans by mid-April to relocate to “less-costly areas of the country.” But less than half of government offices are in a lease period that allows them to be terminated without penalty, according to government data.

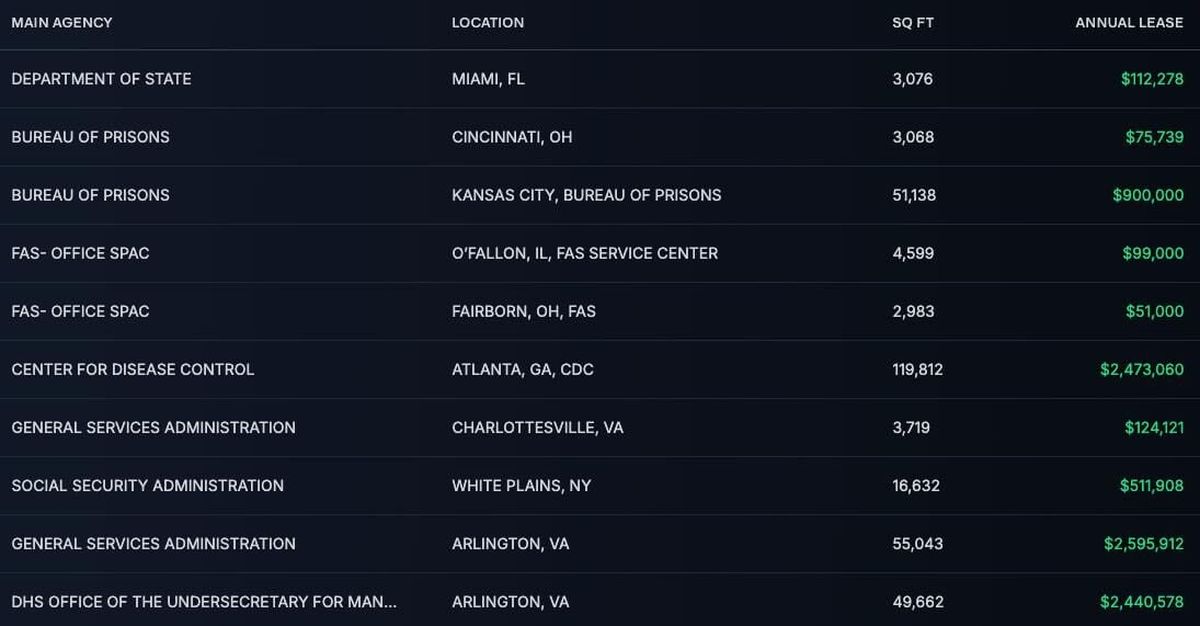

On its website, DOGE lists 748 lease cancellations as of Monday, which it claims will save taxpayers $660 million. But a Washington Post analysis found many of the savings estimates are wildly inflated. For example, many of the calculations assumed leases would continue for an additional five years, whereas most of the largest leases listed were already set to end in the next year or two.

Even when leases enter the “soft term” - the period in which the government can end them unilaterally - it’s often a better deal for the government to keep them, said Diana Parks, chair of the National Federal Development Association, which represents landlords who lease to the federal government. That’s because rents are often lower in the soft term and moving to new leases can be considerably more expensive.

Federal agencies and offices have been directed in recent weeks to provide justifications of continued occupation of buildings with soft-term leases. “I’ve been perplexed that the government is talking about canning soft term all around,” Parks said, adding, “It’s usually a pretty good deal for the government to keep leases during the soft-term period.”

The terminations have repercussions far beyond the government and its workers. Landlords who rely on the federal government - broadly considered a stable long-term tenant - suddenly face the prospect of massive vacancy and financial risk, further harming a commercial real estate market that’s still suffering from the aftereffects of the pandemic-era shift away from office work.

Lease terminations are likely to affect local economies around the country, but the D.C. region will almost certainly bear the brunt. About 17 percent of employed residents of the region are federal government workers, according to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, and some local landlords get a third a more of their revenue from government leases, Bisnow has reported. An analysis by the real estate services firm CBRE found 60 soft-term leases in the region, totaling about 2.75 million square feet.

All these changes come against the backdrop of massive cuts to the federal workforce, which could allow for offices to be closed and consolidated without the need to sign new leases. But the Agriculture Department employee questioned why the leases are being terminated before anyone knows the full extent of the staff cuts.

“I think it really highlights the lack of strategy and cohesiveness in this approach,” she said, noting that the administration gave agencies a March 13 deadline to submit plans to slash their staffs. “If March 13 is going to be the end of the first [reduction in force] period, then you start terminating leases, not before.”

Several federal workers expressed doubt that the cuts will really reduce waste and spending, when offices that promote accountability are being targeted and the return-to-office mandate requires a certain amount of workspace.

“If this administration is truly interested in saving money, then you’d be having all the people on a state and regional level at 100 percent telework,” the Agriculture Department worker said. “We’re moving in the wrong direction if you want to be saving money.”

Amid the various directives, the lawsuits, the judges’ decisions and the promises to appeal those decisions, many federal workers don’t know where they’ll be working a few months from now, or whether they’ll still be employed. But they do know they are confused and frustrated.

“It’s just so uncoordinated and so unplanned,” said the Interior Department employee, recounting the first week everyone on his team returned to the office that will soon no longer be their office. “The landlord came in; and I had to explain to him what was going on from my non-knowledgeable point of view. He was just stunned at how much this could affect the local community.”

The landlord tried to contact his leasing agent at the GSA, the employee said, only to learn that the agent had taken the deferred resignation deal following the Trump administration’s “fork in the road” email and was no longer working.