NASA telescope will study what put the bang in the big bang

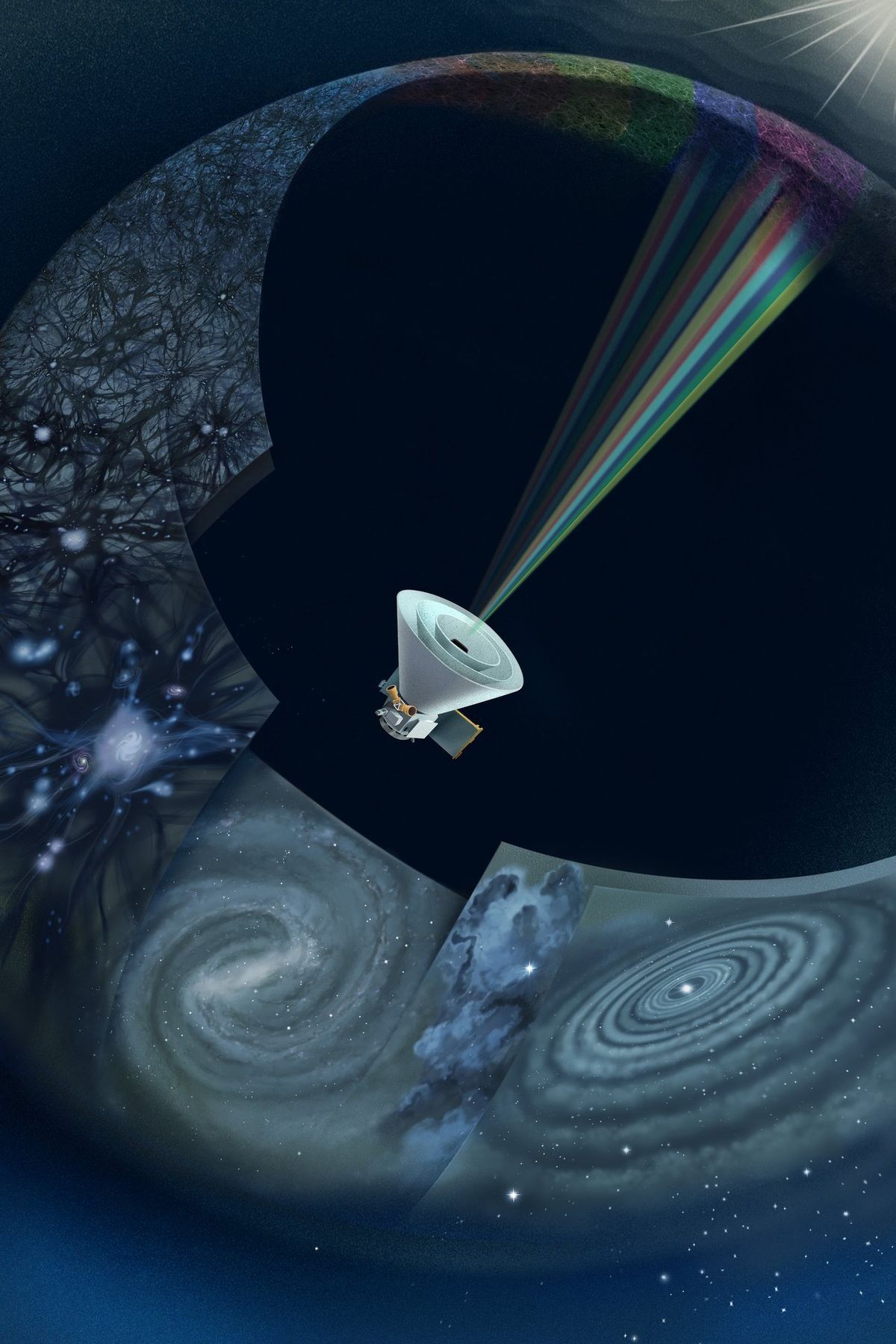

An artist’s concept of SPHEREx. MUST CREDIT: JPL-Caltech/NASA (Caltech/NASA/Caltech/NASA)

How did the universe begin? A compact NASA space telescope that uses less power than a refrigerator is poised to chip away at that large question.

Called SPHEREx, and set for launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base no sooner than Tuesday night, the telescope will go into a polar orbit that will allow it to survey the entire sky in 102 different wavelengths every six months.

The primary goal of the mission is to probe the theory of “cosmic inflation.” The gist of the theory is that, back in the day – well, literally at the beginning of time and space, the “big bang” – the universe went through a brief period of exponentially accelerating expansion.

This kind of cosmic expansion would not have been slow and steady. Inflation is an unimaginably faster. It would have transformed the universe from tiny to cosmic is a snap.

“How can you ask a bigger question than ‘What was it like at the origin of the universe?’ ” said Phil Korngut, an astrophysicist at Caltech and the SPHEREx instrument scientist.

The telescope will gather light from about 450 million galaxies and create a three-dimensional map of the universe, including how everything has evolved through time. The goal of SPHEREx (a merciful acronym, for “Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer”) is to gather large amounts of data on the positions of galaxies relative to one another in a large volume of cosmic space.

The galaxies are not randomly distributed, but instead form clusters and superclusters and filament-like structures at large scales, with voids in the mix. By looking at the distribution of galaxies across large swaths of the sky, scientists hope to discern evidence about how the early universe looked before it became cosmically large. That in turn could narrow the number of plausible inflation theories.

Right now there are many distinct inflationary theories – it’s the Wild West of cosmology. In trying to expose these theories to hard data, and narrow the range of possibilities, a mission like SPHEREx could lead to a new understanding of fundamental physics, said James Fanson, project manager for SPHEREx at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Much of what physicists know about our universe comes from particle accelerators – huge contraptions, such as the one deep underground near Geneva, where atomic particles are sent on a collision course to see what happens. But the universe can do that kind of thing better.

“There’s a limit in what we can do with particle accelerators on the ground when we are smashing atoms together. But the universe is really a high energy experiment,” Fanson said. “There are very energetic processes in the universe going back to the big bang singularity. We have the opportunity to discover something fundamental about the universe.”

Other astronomical surveys have also looked at large numbers of galaxies, but this mission is going wide rather than deep, scanning the whole sky.

“We’re casting a broader net,” said the mission’s top scientist, James Bock of Caltech. “We’re interested in these statistical fluctuations on large scales, where the signature of inflation is the cleanest.”

The telescope will also search for evidence of water and organic molecules in star-forming regions in our own galaxy.

Inflationary theory dates to the late 1970s and early 1980s, when physicists were trying to understand why the universe is so uniform at the largest scales, including the cosmic microwave background radiation. MIT physicist Alan Guth, among the founders of inflation theory, had a revelation that the appearance of the cosmos could be explained by a brief inflationary period.

In an article published in the MIT Physics Annual 2002, Guth wrote that the big bang theory is incomplete: “[T]he theory says nothing about the underlying physics of the primordial bang. It gives not even a clue about what banged, what caused it to bang, or what happened before it banged. The inflationary universe theory, on the other hand, is a description of the bang itself … “

But did that really happen? And if it did happen, how? What were the physics involved?

“We don’t yet know for sure if inflation happened,” Jo Dunkley, a Princeton University astrophysicist, said in an email. “And if it did, we still want to know how it happened – what physical ‘field’ (or multiple fields) was around at that time that drove the rapid expansion, before there were any particles.”

She said SPHEREx could help shine light on inflation theory because it’s an all-sky survey that will measure the distribution of galaxies “and will be able to look for these subtle signatures in how galaxies are positioned. It will be really unique in observing the sky in this way.”

Michael Turner, a cosmologist at UCLA and one of the architects of inflation theory, said in an email that “the relationship of inflation and the big bang is not settled or simple.”

One possibility is that an inflationary event was our big bang, and anything that happened before that point will probably be impossible to measure. But he added, “If you are a multiverse person, there were and continue to be an infinite [number] of big bangs occurring creating the disconnected regions we cannot see.”

So there’s that nugget to ponder: The universe we see, which is big, may be only the tiniest, infinitesimal fraction of the grander thing out there.