In ‘My Documents,’ passive Americans accept their dystopian reality

In a May 2000 essay for Essence magazine, Octavia Butler wrote that “to try to foretell the future without studying history is like trying to learn to read without bothering to learn the alphabet.” History clearly inspires Kevin Nguyen’s dystopian second novel, “My Documents,” which imagines a near-future in which, following coordinated terrorist attacks by Vietnamese perpetrators, 1 million Vietnamese Americans are imprisoned in the same way Japanese Americans were during World War II.

The consensus on the need for this fictional incarceration resembles the real-life prelude to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The legislation, named the American Advanced Protections Initiative – a clever repurposing of the Asian American Pacific Islander acronym – passes “with hardly any resistance from the Democrats.” Hundreds protest in New York, but “surprisingly few Asians” show up. To soften the injustice, the government mandates the term “detention” rather than “internment” when describing the legislation, and journalists comply. A U.S. senator known as “The War Hero,” an obvious stand-in for John McCain, compares the living conditions in the facilities to “summer camp.” Jen, an NYU student and one of the book’s protagonists, simply tries “to make the best of” her new life in the parched desert of central California.

Some Vietnamese Americans are spared, including Jen’s half-White cousins Alvin and Ursula. An ambitious journalist, Ursula suspects that her surname – Carrington – is the reason she wasn’t rounded up, while Alvin’s employer, Google, files for exemptions for its Vietnamese American workers. Ursula has been stuck writing celebrity pap for an entertainment website, but when she receives leaked messages from Jen, she seizes the opportunity to become the serious journalist she’s always wanted to be.

Many of the main characters seem either unwilling to reflect upon or largely oblivious to America’s long history of racist policies. Alvin learns about Japanese incarceration while visiting a museum near Google’s campus. The book contains a single mention of 9/11, a similarly coordinated terrorist attack, but no one connects what’s happening with Vietnamese people to the Bush-era requirement that visitors and immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries register with the government, a policy that the ACLU called racial profiling. When Jen discovers that one of the camp’s underground publications is named Korematsu, after Fred Korematsu, who in 1942 refused to turn himself in and unsuccessfully sued the United States for his freedom, she realizes that “she’d forgotten to look up the Wikipedia entry for it.”

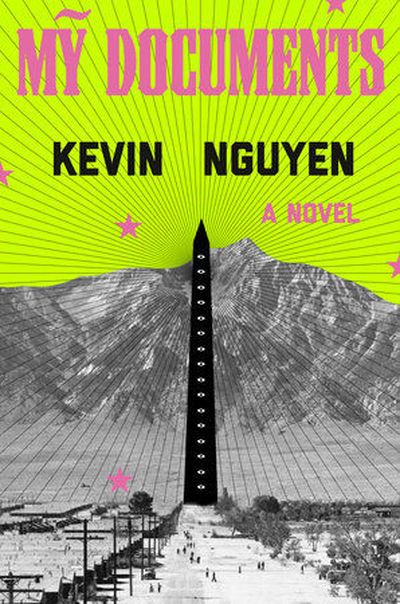

Nguyen’s barbed social commentary convincingly depicts a dystopian America that’s both distinct from and similar to the country we know today. At the center of Jen’s camp is the Tower, an obelisk that emits an electric fog blocking wireless signals. This isolation from modern technology spawns a digital piracy ring named El Paquete, which smuggles movies, TV shows, music and video games into the camps via USB drives. Through El Paquete, Jen passes her messages to Ursula.

While the world-building successfully critiques tech giants, the mainstream media, corporate influence and public education, it also hems in plot and character development. Because Jen is just trying to make the best of her situation, her coming-of-age experiences – developing crushes and watching her brother play football – feel strangely inconsequential compared with the dramatic weight of losing one’s freedom. Ursula’s quest for journalistic credibility makes sense in the America we know now, but in a passive, amnesiac America where the mass imprisonment makes barely a ripple in the news cycle, Ursula’s rise as a reporter seems dubious. It’s unclear why her stories about El Paquete and Google’s erasure of the camps from satellite imagery would finally shake the public from its malaise.

Through Ursula’s narrative arc, the book seems more concerned with critiquing the way people consume trauma via the media than it is with the actual trauma of imprisonment. Ursula admits to feeling guilt about using Jen’s experiences without her permission to boost her own career, but it doesn’t stop her from cashing in on a high-six-figure book advance and an eight-part documentary series on Netflix.

The book’s violent and tragic climax feels both inevitable and somewhat discordant with the rest of the book, which floats forward on first romances, road trips, football games and interoffice flirtations. A lengthy denouement ties up loose plot threads, some of which feel overdetermined, while others seem unnecessary. “Mỹ Documents” is a timely and intermittently chilling reimagining of history, but it also presents a nation that has stopped questioning its racism. That makes for a convincing dystopia, but it elides the more complex conversations about race going on in America at this very moment.

Leland Cheuk is an award-winning author of three books of fiction, most recently “No Good Very Bad Asian.” His work has appeared on NPR and in the San Francisco Chronicle and Salon.