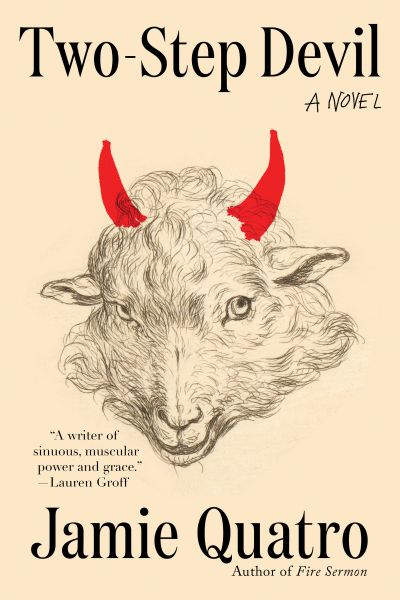

‘Two-Step Devil’ bears witness to the fragile state of human existence

In Jamie Quatro’s fiction, a person is a burning thing: a voracious creature, hot with emotional, sexual and spiritual needs; prey to the squalid demands of embodied existence. Surely it’s my imagination, but when I read Quatro – whether her story collection, “I Want to Show You More” (2013), her debut novel, “Fire Sermon” (2018), or her new book, the novel “Two-Step Devil” – I can’t shake the sense that the pages feel warm to the touch. I see, in my mind’s eye, her sentences threaded with muscle and sinew, letters glistening with sweat and blood.

Reading is always, to some extent, a physiological experience, our bodies animated by the exercise of empathic witness, of readerly surrender and interrogation. Still, Quatro’s work coaxes an even more sustained awareness of our vulnerable physicality, for it insists upon the body’s centrality to human experience. One may submit to the body’s clamors, or strain toward the numbing weightlessness of disassociation – that “floating up and watching yourself,” as a character in “Two-Step Devil” calls it – but across Quatro’s oeuvre, there is no forgetting that selfhood is material: pulp and tissue and guts.

Quatro’s first two books unite crises of erotic desire – often in the context of an extramarital affair – with crises of faith. In “Two-Step Devil,” sex recedes from the narrative’s focus, although it pervades the contextual background. We meet the novel’s central character in adulthood, and we know him throughout the brunt of the text as an ailing 70-year-old man who calls himself the Prophet and whose preoccupations are entirely spiritual. But we are privy to shards of his younger consciousness, when his name was Winston and he “was a regular devil like the rest,” tempering the grind of his life with brothel visits and booze. Eventually, he marries a churchgoing woman and settles into a milder quotidian. When he rescues Michael, a teenage foster child forced into sex work, he is an old widower determined to banish any lingering sexual desires – “sins … of the mind,” he calls his stray erotic daydreams – that might seduce his attention away from the Lord. This is not a lusty book, but it is without a doubt Quatro’s fleshiest, and her most formally inventive. The bodies in “Two-Step Devil” suffer mightily; they are impoverished, diseased, addicted, ravaged by sexual abuse. “You fleshsacks will want to look away,” the devil of the title goads the reader. “You must bear witness.”

One gets the sense that he is addressing a particular type of fleshsack who expresses a distinct sensibility: namely, the liberal, educated reader with a robust bank account, whose primary exposure to hardship arrives through the medium of literary novels. Together with its other luxuries, socioeconomic privilege entails the ease of coherence: a life in which questions seem to have ready, comfortable answers, and ideology gels smoothly against affluence’s psychological and financial balustrades.

Neither the Prophet nor Michael enjoy these advantages. Their realities are fraught and fractured, their worldviews cobbled together from their oft-devastating archives of experience. The Prophet’s chosen moniker indicates the strident religious fixation that shapes his life and derives from the apocalyptic visions he believes are God-sent. He paints these visions across the surfaces of his secluded cabin in Lookout Mountain, Ala., built around the trunk of an oak tree, which the Prophet refers to as the Tree of Life. Before Michael’s arrival, he lives alone. His wife died painfully from breast cancer years earlier; his only son keeps his distance.

The Prophet first sees Michael from afar when he is rummaging at the local junkyard. After being ushered into the bathroom of an abandoned gas station, she re-emerges with zip-tied wrists, wearing “a short dress that sparkled like flashbulbs when she moved.” The Prophet quickly decides to free Michael from these obviously abusive circumstances. He also determines that she is his “Big Fish”: a holy messenger who will travel to Washington to tell the president about his prophecies and thereby sound the alarm “about things yet to come, the visions of the Earth’s last days.”

For reasons that become clear, Michael cannot be honest with the Prophet about her situation; nevertheless, she is moved by his gentleness and returns his kindness with an almost daughterly affection. Unsurprisingly, she does not absorb or even entirely comprehend his feverish beliefs, but they also do not agitate her. “(He treated) me nicer than anyone,” she thinks to herself, astonished that he “never let me touch him that way even though I tried at first.”

Fittingly, the structure of “Two-Step Devil” gestures to its characters’ painful and disrupted histories through its own resistance to teleology. The narrative glides back and forth across time, as if embodying the consciousness of a person mining the depths of their memory, and it occupies multiple perspectives. In the first half of the novel, the reader keeps close company with the Prophet, and in the latter half, we follow Michael as she sifts through brutal recollections of sex abuse and embarks on a harrowing journey. Then, the novelistic scaffolding falls away entirely.

The last pages of the book purport to give the reader “the truth” about Michael’s life after she parts ways with the Prophet, but the reader can’t be certain of its validity. For at this point, we’re in the hands of two narrators: one a disembodied omniscient voice, and the other an entity we’re primed to distrust, Two-Step himself. Who, now, is pulling the narratorial strings? Or by asking that question, has the reader been seduced by the promise of tidy linearity inherent to an antiseptic typeset page? Every story is an invention without a true material analogue; the teeming world it grapples to contain will always exceed its machinations. In the end, we are left with our bodies and how they absorb the meanings we struggle to make.

As the novel reaches its conclusion, its titular character looms large, issuing provocations to the Prophet and, finally, to his fleshsack readership. Simultaneously, the text’s escalating fragmentation summons our attention to the artifice of genre – a latter section of the book even takes the form of a stage play. One begins to question the possibility of a coherent spiritual framework when the world’s essential chaos rebukes any such legibility. As Two-Step taunts: “You cannot stand for the horrific and the beautiful to touch, cannot fathom a system in which one person benefits from the suffering of another. But so it is. So Creator has ordained.”

If Quatro has written a song for the frail fleshsack, she has, too, intimated humanity’s cowardice in storytelling, the entwined “horrific and beautiful” realities we balk at and, in desperate self-preservation, refuse to witness.

Rachel Vorona Cote is the author of “Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today.”