The remains of Spokanite Janice Blackburn Ott were found 50 years ago. She’s so much more than a Ted Bundy victim

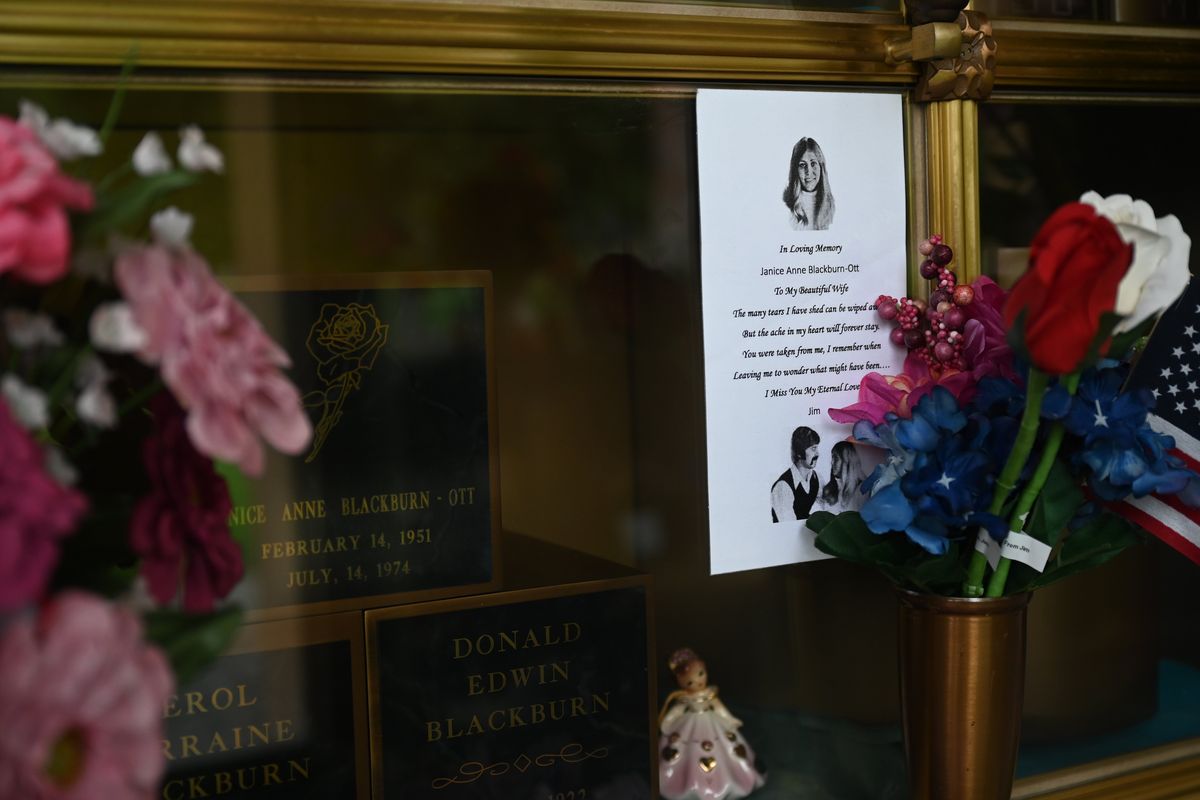

Fifty years after the remains of Janice Blackburn Ott were found in Issaquah, Washington, her urn sits inside a glass case at Fairmount Memorial Park in Spokane, still empty.

King County lost Ott’s remains after years keeping them for evidence against serial killer Ted Bundy, said her older sister, Illona Clark. But the memory of Ott is still everywhere – Clark thinks of her every single day, she said.

The cremation niche inside the Sunset Mausoleum holds the remains of Ferol Blackburn, Ott’s mother; and Donald Blackburn, Ott’s father, who was a former superintendent for the Spokane School District. Next to the glass hangs a vase equipped with pink, blue and white flowers. A laminated note from Ott’s husband, Jim, is taped in the corner, where he wrote the ache in his heart from her murder will “forever stay.”

“You were taken from me, I remember when,” the note says. “Leaving me to wonder what might have been.”

Ott, a 23-year-old caseworker for the Youth Services Center in King County, left her house in Issaquah to ride her yellow 10-speed bike to Lake Sammamish State Park one summer day in 1974. She planned to sunbathe in the July weather among the massive crowds with the same idea. It was there that she met a man witnesses knew as “Ted” – he approached Ott in the parking lot with one arm in a cast and asked for help loading something from his brown Volkswagen Beetle, according to The Spokesman-Review archives.

She suddenly vanished along with 18-year-old Denise Naslund, who was also at the park that day. No one could have known at the time that the man would turn out to be a notorious serial killer who disarmed women by using casts and crutches to elicit pity.

“She was the nicest person. And she couldn’t say no,” Clark said. “That’s why she was killed.”

Clark and her husband were living in Spokane, so had no way to look for Ott after she went missing.

“We had jobs,” Clark said. “We assumed the police were doing their job looking for her.”

Adding to the confusion, the Clarks got a letter from Ott that she had sent before her killing.

A package also came in the mail around the same time. Illona Clark’s longtime husband Gary remembered voicing interest in a book he wanted to read, and opened the mail to discover it was the same book. It wasn’t weird for Ott to send letters and gifts and be in continual contact, because “that’s just the kind of chick she was,” Illona Clark said.

It took two months before Ott’s and Naslund’s remains were found by grouse hunters in a wooded, remote location 2 miles east of the state park. The “Ted” who had lured Ott away under the guise of an injury was discovered to be Bundy, who was executed after he confessed to Ott’s murder along with the killings of 29 other women across seven states.

“As awful as it was when they did find her, we knew what happened,” Gary Clark said.

Bundy seems to be all the public remembers, Illona Clark said. More than a dozen films and even more documentaries bear his name, with each plotline revolving around his life, his murders or exclusive audio recordings of his death row confessions.

But in the 50 years since Ott’s murder, the couple has never once been approached by a reporter. Police haven’t even given them a call, they said. Documentary filmmakers are usually the ones to reach out, but the film that is pitched is never about her sister, Illona Clark said – “It’s always about the monster” who ended her life. The two even refused to use Bundy’s name when speaking of him, but mostly declined to speak about him at all.

“You hear about him all the time,” she said. “You don’t hear about his victims.”

When people read about Ott, they might only see her referred to as “the Issaquah woman” in old newspaper clippings or television stories. Except Ott wasn’t just an “Issaquah woman.”

Ott was born in Oregon, records show, but spent most of her years in Spokane. She attended Finch Elementary School and Glover Middle School in Northwest Spokane and spent her high school years at Shadle Park High School where she graduated with high honors in 1969.

A Shadle Park yearbook from that year is filled with photos of Ott, who was referred to as “Jann” back then. Former classmates remember calling her “Janny,” someone who always trusted people would do the right thing and someone everybody liked, according to previous reporting from The Spokesman-Review.

The yearbook shows she was active at school and with her studies. She spent time as a National Honors Society and ASB student; joined the Hi-Lassies, a group of cheerleaders; was a secretary for the Girls’ League; a class treasurer; a chairman for the commercial club and part of the art, ski and pep clubs.

In one photo from the 1969 yearbook, she is shown with shorter hair, wearing a plaid dress.

“Taking copious notes, Girl’s League Secretary Jann Blackburn keeps the minutes during a Girls’ League meeting this fall,” the caption said.

A scholarship fund was even started at the school in her honor.

Ott went on to attend Eastern Washington University, where she kept exceptional grades, and graduated with a degree in social work. While living with her parents across the street from Glover Middle School, she would occasionally walk over to the school’s campus, but would be mistaken for a middle schooler. The Clarks laugh about it now.

“She was like, ‘Um … I’m in college,’ ” Gary Clark said. “She was a tiny little thing, under 5 feet tall.”

Everybody had something pleasant to say about young Janice Blackburn – and she was “everything we could want in a girl,” her father said in a 1989 interview with The Spokesman-Review. She married Jim Ott and relocated to the Seattle area with her husband because the couple found jobs there. Illona Clark was in her wedding and would travel to Seattle to see her sister often, she said. The two were “best friends.”

There isn’t one specific memory that stands out to the Clarks because they cherish all of them, they said. But sometimes, Illona Clark will even find herself laughing and think, “It would be so funny if Janice was with us.”

“She was so funny, so pretty and sweet. Everybody loved her,” Illona Clark said.

Ott wasn’t the only woman murdered by Bundy with Spokane ties. Susan Rancourt, a student at Central Washington University, was abducted in April 1974 and found dead a year later. She also attended Glover Middle School in Spokane, and Ott dated her brother, Denny, at one point.

Ott’s parents sued the King County Medical Examiner’s Office for $2 million after it lost their daughter’s remains. Naslund’s family did the same, and both families were paid, but the settlement amount is unclear in former reporting. The office had held onto the remains in case Bundy returned to Washington to stand trial, records say, but may have accidentally cremated them when the office moved to Harborview Medical Center in 1976.

The Clark couple later had two children, a son and a daughter. The abduction and murder of Ott made them overly suspicious of people, they said. When the children were smaller, the couple was slightly overprotective.

They still talk about their beloved 23-year-old sister, though, and the Clarks visit her memorial every time they travel from California back to Spokane, even though her remains aren’t there.

“I wish she could’ve seen our grandchildren,” Gary Clark said. His wife chimed in and agreed: “She would have been a perfect aunt.”