James Earl Jones, actor whose voice could menace or melt, dies at 93

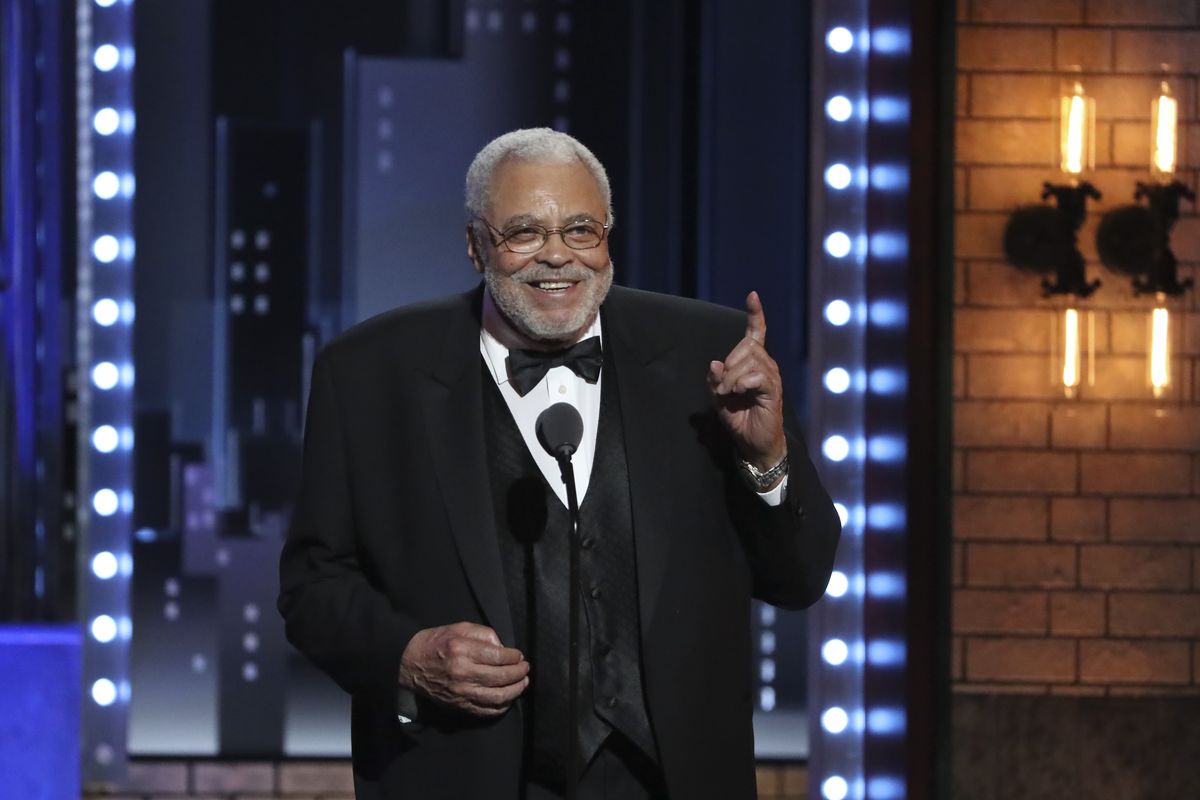

James Earl Jones, who had received a Tony nomination for his role in the Broadway revival of “Gore Vidal’s The Best Man,” at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theater in New York, May 25, 2012. Jones, once a stuttering farm child who became a voice of rolling thunder as one of America’s most versatile actors in a stage, film and television career that plumbed race relations, Shakespeare’s rhapsodic tragedies and the faceless menace of Darth Vader, died on Monday, Sept. 9, 2024, at his home in Dutchess County, N.Y. He was 93. (Todd Heisler/The New York Times) (TODD HEISLER)

James Earl Jones, once a stuttering farm child who became a voice of rolling thunder as one of America’s most versatile actors in a stage, film and television career that plumbed race relations, Shakespeare’s rhapsodic tragedies and the faceless menace of Darth Vader, died Monday at his home in Dutchess County, New York. He was 93.

His agent, Barry McPherson, confirmed the death, the Associated Press reported.

From destitute days working in a diner and living in a $19-a-month cold-water flat, Jones climbed to Broadway and Hollywood stardom with talent, drive and remarkable vocal cords. He was abandoned as a child by his parents, raised by a racist grandmother and mute for years in his stutterer’s shame, but he learned to speak again with a herculean will. All had much to do with his success.

So did plays by Howard Sackler and August Wilson that let a young actor explore racial hatred in the national experience; television soap operas that boldly cast a Black man as a doctor in the 1960s; and a decision by George Lucas, the creator of “Star Wars,” to put an anonymous, rumbling African American voice behind the grotesque mask of the galactic villain Vader.

The rest was accomplished by Jones himself: a prodigious body of work that encompassed scores of plays, nearly 90 television network dramas and episodic series, and some 120 movies. They included his voice work, much of it uncredited, in the original “Star Wars” trilogy, in the credited voice-over of Mufasa in “The Lion King,” Disney’s 1994 animated musical film, and in his reprise of the role in Jon Favreau’s computer-animated remake in 2019.

Jones was no matinee idol, like Cary Grant or Denzel Washington. But his bulky Everyman suited many characters, and his range of forcefulness and subtlety was often compared to Morgan Freeman’s. Nor was he a singer; yet his voice, though not nearly as powerful, was sometimes likened to that of the great Paul Robeson. Jones collected Tonys, Golden Globes, Emmys, Kennedy Center honors and an honorary Academy Award.

Under the artistic and competitive demands of daily stage work and heavy commitments to television and Hollywood – pressures that burn out many actors – Jones was a rock. He once appeared in 18 plays in 30 months. He often made a half-dozen films a year, in addition to his television work. And he did it for a half-century, giving thousands of performances that captivated audiences, moviegoers and critics.

They were dazzled by his presence. A bear of a man – 6 feet, 2 inches tall and 200 pounds – he dominated a stage with his barrel chest, large head and emotional fires, tromping across the boards and spitting his lines into the front rows. And audiences were mesmerized by the voice. It was Lear’s roaring crash into madness, Othello’s sweet balm for Desdemona, Oberon’s last rapture for Titania, the queen of the fairies on a midsummer night.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.