Tuesday was the first day at Spokane Public Schools. For some, it’s their first day of school in America

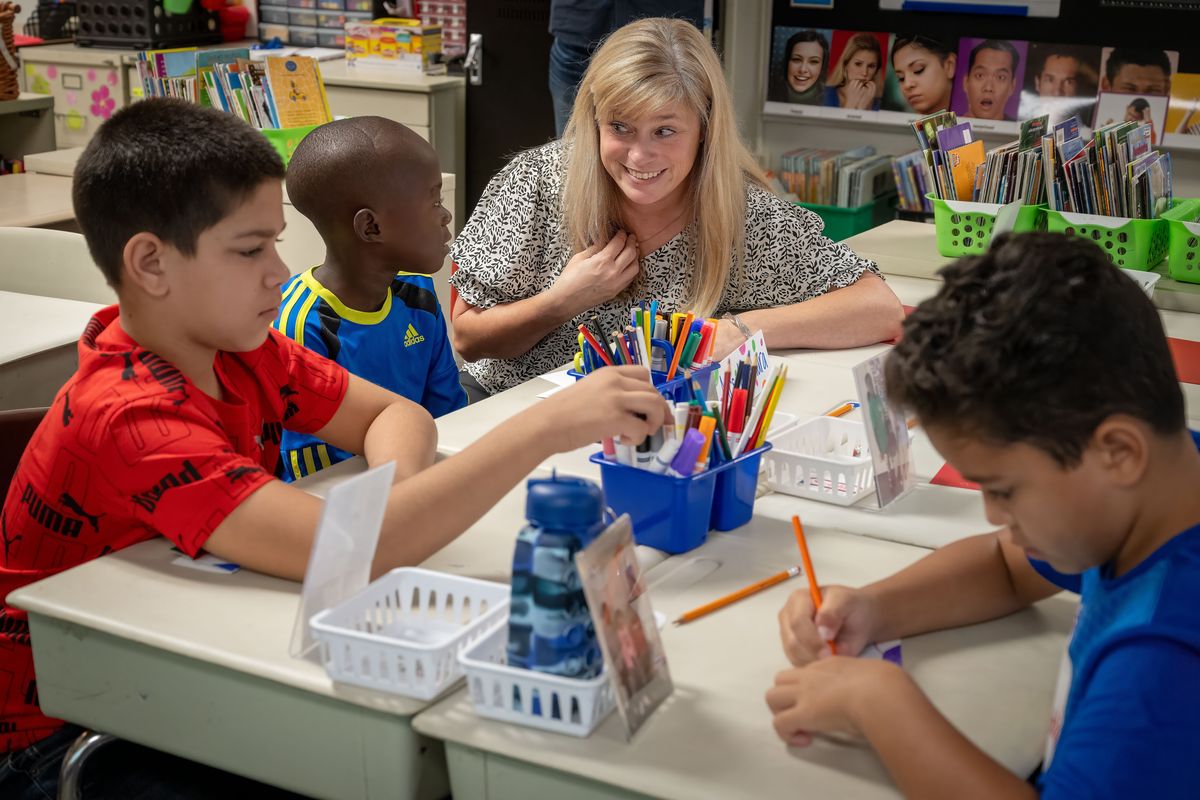

At Garfield Elementary’s Newcomer Center, fifth-grader Awet is glad to see friend fourth-grader Ezekiah on the first day of school Tuesday in Spokane. (COLIN MULVANY/The Spokesman-Review)

The first day of school is momentous enough in any student’s life. It’s a day typically marked by nervous excitement to cross the threshold into a new classroom where they’ll spend 180 days of their lives.

The 29,000 kids enrolled in Spokane Public Schools marked that milestone on Tuesday, but the novelty didn’t end there for a handful of these pupils at Garfield Elementary. To them, Tuesday was their first day in an American school.

Over 100 students each year enroll at Spokane Public Schools unable to speak much English, some seeking refuge or immigrating to the United States with their families.

To ease their transition to a new country and new school system, nine schools in the district offer “newcomer center” classrooms. Students spend up to a year in these classrooms learning English and cultural norms in their new country before enrolling in general education at their neighborhood school.

At Garfield Elementary, teacher Erica Uyehara started her second year overseeing a newcomer center with bilingual specialist Nedhal Albayabi. There’s one word that comes to Uyehara’s mind when describing her time in a newcomer center: “Magical,” she said.

“They’re working to negotiate through so many of our huge systems, whether it’s housing, food, clothing, any services, so this is just one system that we get to kind of wrap around and be as supportive as possible,” Uyehara said. “It’s not just their child that gets to have their first day in American school – it’s the whole family unit. How can we help to make this year successful for you and help them launch into their academic career in America?”

The newcomer center is new to Garfield Elementary after an “unprecedented” enrollment in the centers last school year, said Heather Richardson, director of English language development at the district. To accommodate for the impossible-to-predict amount of kids, Spokane last year opened four additional classrooms in the middle of the school year.

At the end of last school year, there were 190 students in newcomer centers, though that number doesn’t include the additional kids who started the year in newcomer centers and transitioned to general classrooms before the end of the year.

Pennants of flags from around the globe drape from the ceiling of Uyehara’s classroom in the Emerson Garfield neighborhood school, where she arranged red folders labeled with each of her pupils’ names on their desks ahead of their arrival. Though 10 folders occupy 10 desks, she has no idea how many of her kids she’ll see on the first day.

It takes weeks before all of her pupils are in school as their families adjust to the bussing system. Even then, her classroom is constantly in flux as new students arrive and others graduate from the program and into their neighborhood school.

“All of us have learned now to just be adaptable and flexible. It’s scary – you’re getting on a bus and you might not know anyone, you may not be able to speak to anyone. And as a parent, how scary,” Uyehara said while sliding family photos into picture frames at each student’s desk.

“The goal is it’s a source of comfort for them,” she said of the grinning portraits she took when she met families before school started.

That’s the goal behind much of Uyehara’s classroom, she said. She intentionally curates a safe and calming atmosphere she hopes puts her kids at ease on what could otherwise be a turbulent day. The clamor of other Garfield pupils outside the newcomer center door is a stark contrast to the Zen she fosters inside, where twinkling Christmas lights and several small lamps cast an ambient glow around the room. Slow classical music covers the silence of her students, some of whom eventually start saying one-word responses in English.

Six of Uyehara’s 10 enrolled students arrived on the first day of school; she guided them through their activity decorating a name tag for their desks through animated gesticulations, pointing and one-word directions.

“I joke with other teachers that it’s nice if you have a theatre background,” she said. “That’s where you tap into, you’ve got to be animated and use lots of visuals.”

The 10 enrolled students hail from eight different cultures and speak myriad languages, including Spanish and Tigrinya, a language used widely in Eritrea and Ethiopia. Students speak little to no English when they enter newcomer centers.

“This is, for some of them, the first formal information language training they’ve had in English,” Uyehara said. “For some, they might have had something at their previous schools. For others, they’ve never been to school, so the experiences are so different.”

The newcomer center is as much for teaching English and math fundamentals as it is for familiarizing students and families with the American education system and cultural norms that may differ from their countries of origin.

Richardson said sometimes students need guidance in navigating their bell schedule, the lunchroom, identifying the foods they’re served, using water fountains and playground etiquette, to name a few.

His second year working in Spokane Public Schools, Albayabi is a recent graduate from Eastern Washington University where he studied psychology and Arabic. His degree helps him understand how his kids’ brains may be working and how to calm them from stress. He taught 12 years in his home country of Saudi Arabia and teaches Arabic on the weekends.

Despite his resume that has led him to his role as a bilingual specialist, his experience that best helps him support his newcomer center students isn’t an academic one.

“Don’t forget, I was an immigrant,” Albayabi said. “I came here to America 10 years ago and I didn’t speak English at all. I understand the challenges they’re going to face.”

Fluent in Arabic and English, Albayabi has worked with students from Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Egypt in their native tongue. Though they can verbally understand each other, he benefits from recognizing that each is their own culture and awareness of some of the unique contexts in which his students may be coming from.

“Anything I can do to make them more comfortable in a new environment, a new culture, everything is new to them,” Albayabi said. “Whatever they need to feel safe, comfortable, that’s what I was focused on.”

Parents and students learn together to navigate other potentially-confusing structures of the education system with the aid of translators working in the English language development department. The department has grown in tandem with an increased need for language services.

In April 2014, 1,441 students received English language development services in varied capacities throughout the district, though there is significant variation in the number of students depending on the time of year as they move through the department.

A point in time snapshot from February 2024 counted 2,373 students receiving services.

There are around 70 languages spoken by Spokane Public Schools’ families, though 80% of non-English speakers use the same 10 languages: Marshallese is the most common, followed by Spanish, Russian, Arabic, Swahili, Dari and Pashto (both official languages of Afghanistan), Ukrainian, Karen from Southeast Asia, and Kinyarwanda, which is spoken in Rwanda and adjacent African countries.

Staff communicate with those who use the remaining 60 languages using a phone translator service. Translators guide families in signing up for bussing, filling out other school paperwork and working with other support services they may need.

While first day jitters are exacerbated by students new to the country and their school, Uyehara watches her pupils climb out of their shells and grow confidence as English speakers and in their new environment.

“Once we know what to do and the language is layered in, we add on. Confidence is built, and it’s pretty amazing to watch the transformation over the year,” Uyehara said. “It’s really, I don’t have another word, it is magical. It’s very magical.”