‘A sin on our souls:’ Biden condemns U.S. Indian boarding schools

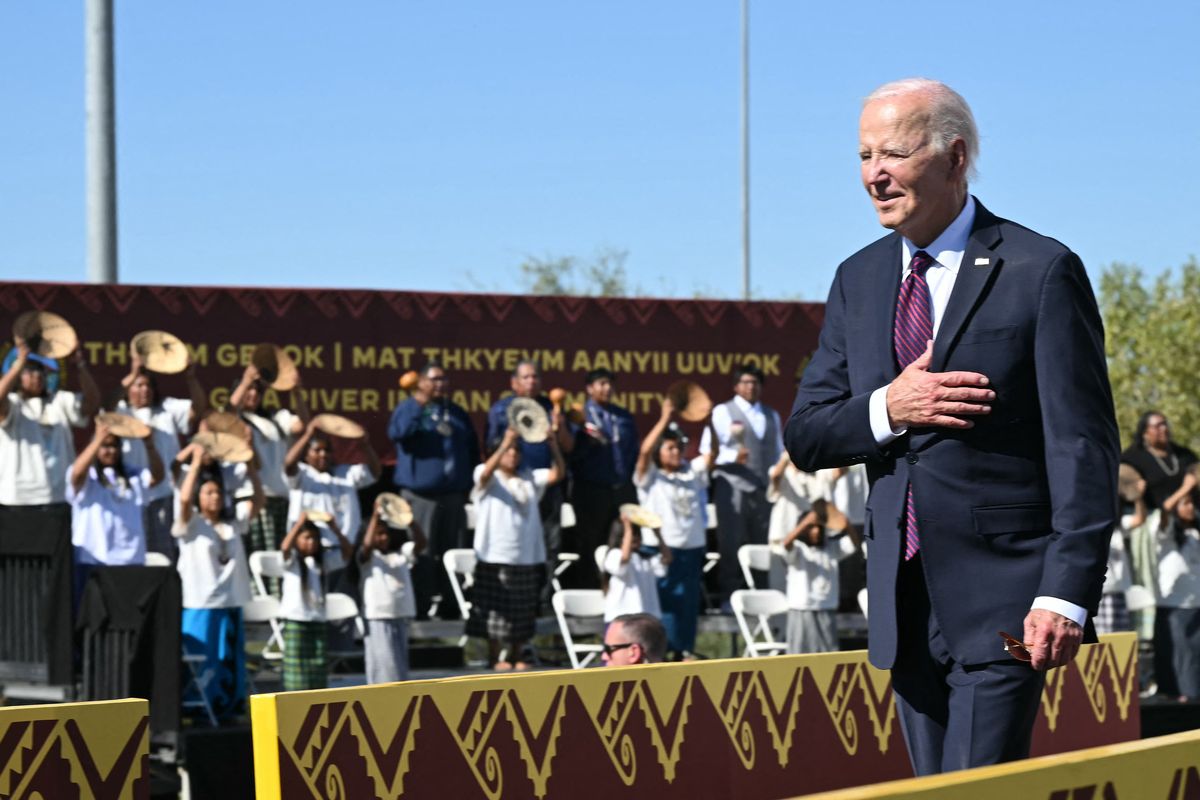

Biden prepares to formally apologize for the U.S. government’s role in running hundreds of Indian boarding schools. He called the schools “a sin on our souls.” (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

GILA RIVER INDIAN COMMUNITY – President Joe Biden apologized to Native Americans on Friday for the U.S. government’s role in creating and operating Indian boarding schools that for 150 years aimed to assimilate Native children by taking them from their families and erasing their languages and culture.

As he spoke, a large crowd of tribal leaders and community members cheered. Survivors of the schools cried, listening to words they said they never thought would come.

“The federal government has never formally apologized for what happened until today. I formally apologize,” Biden said as people yelled out, “Thank you, Joe!”

“It did take place,” the president continued. “Darkness can hide much. It erases nothing. Some injustices are heinous and horrific. They can’t be buried. We must know the good, the bad, the truth. We do not erase history. We make history. We learn from history, and we remember so we can heal as a nation.”

In his first visit to Indian Country as president, Biden called government-run Indian boarding schools one of the “most horrific chapters in American history that most Americans don’t even know about.” He described the effort by the U.S. government as “horribly, horribly wrong” and “a sin on our souls.”

Jim LaBelle, who is Iñupiaq and spent 10 years at Wrangell Institute, an Indian boarding school in Alaska, said he traveled from Anchorage with his wife and daughter to hear Biden speak. LaBelle said he was “overwhelmed” by the apology, calling the president’s words “meaningful and powerful.”

Ramona Klein, who belongs to the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, was forced as a child to attend the Fort Totten Indian boarding school 100 miles from her home. As her voice choked up, Klein said, “It has been 70 years since I’ve been in a boarding school, and I’m proud to have lived to see this.”

Biden also touted his record of helping Native American tribes as he aimed to cement his legacy and campaign for Vice President Kamala Harris less than two weeks before Election Day in a tight race for the presidency.

Saying he had come to Arizona to “right a wrong,” Biden praised first lady Jill Biden’s repeated visits to Indian Country and spoke of the traditions that Native Americans had passed down for generations.

“Respect for tribal sovereignty was shattered” by the boarding schools, Biden said.

From 1819 to 1969, the U.S. government operated or paid churches and religious groups to run more than 400 federal Indian boarding schools in 37 states. Biden’s remarks were the first time a U.S. president has apologized for the trauma, abuse and other mistreatment experienced by the tens of thousands of Native children who were forced to attend the schools.

Children were taken from their homes, stripped of their names and given Anglicized ones or were identified by number. Their long hair was cut, and they were beaten if they spoke their tribal languages.

Biden spoke on an athletic field at Gila Crossing Community School, a K-8 school for 500 Native students on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Laveen Village, Arizona, near Phoenix. The school, built in 2019, teaches Native languages and Akimel O’odham and Pee Posh culture. The outside of the school building is emblazoned with tribal language, the kind of words that boarding school students would have been punished for using less than a century ago.

Hundreds of dignitaries, tribal officials, boarding school survivors and their guests arrived to the field with bleachers and a stage under a cloudless sky overlooking the Estrella Mountains. Children from the school and community walked in a processional, singing in their Native language. Teen and elder women wore traditional Native American ribbon skirts, while men donned beaded necklaces and bolo ties. Some survivors were already crying as they walked in to take their seats.

Carletta Tilousi, who belongs to the Havasupai and Hopi tribes, said as she listened to Biden speak, she thought about her relatives who had “experienced pain instilled on them by the federal government” at Indian boarding schools.

“It brought all that pain back to me,” she said. “We need to begin the healing. The apology is the first step.”

The Washington Post first reported on Thursday that Biden planned to apologize to Native Americans during his Arizona stop for the legacy of abuse at the government-run Indian boarding schools.

“It’s a long time coming,” Mary Kim Titla, a member of the San Carlos Apache tribe of Arizona, said as she waited for Biden to begin his remarks. Titla said her mother, Charlotte, is a survivor of the Phoenix Indian Boarding School. “A lot of us here to witness this feel the spirit of our ancestors.”

Wearing a traditional beaded cape necklace made by the sister of another boarding school survivor, Titla brushed away tears as she talked about the children who died at Indian boarding schools.

“I can’t imagine how traumatizing it is to have your babies taken away, and to places far away, to never come home,” said Titla, who has three children and six grandchildren.

Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland became tearful as he said he was thinking of his ancestors.

“I’m like a lot of people here still processing it,” he said. “I feel a lot of emotions. At the top of the list is gratitude. If you think of the journey that this country has been on for over 250 years, almost the entirety of the federal government’s policies for Indian people have been about taking and this day is about healing.

“I’m grateful we have a president who recognizes the humanity of all Americans, including Indian people,” Newland said.

Given the proximity to the Nov. 5 election, Biden’s visit and apology could help spur support for Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign – potentially boosting turnout among Native American voters in a state where their votes could be determinative, said Thom Reilly, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Public Affairs.

“It can change and motivate either young Native Americans who haven’t voted before, or those that are wavering – given that they perhaps might have some concerns,” he said. “This could persuade a group of them to show up at the polls. And I think that’s what it’s all about at this late game – motivating the base and figuring out how you can turn out individuals to show up at the polls.”

Democrats tend to outperform Republicans among Native Americans, making turnout among tribal communities particularly important for Harris’ campaign, which is courting Native American votes in states like North Carolina and Arizona.

While Native American voters across the country could play a role in the outcome of a close presidential race, their votes hold particular sway in Arizona because they make up more than 5% of the population in a state where recent races have been decided by incredibly small margins, Reilly said.

“Our attorney general race was decided by 288 votes. Biden won by about 10,000 votes,” in 2020, Reilly said. “So, targeting these pockets everywhere is what the campaigns seem to be doing. It’s all about turnout at this point.”

The Friday event follows an Interior Department report that found that at least 973 Native American children died of disease and malnutrition at the schools. Many other children were physically abused, sexually assaulted and mistreated. The Interior Department urged the U.S. government this summer to formally apologize for the enduring trauma inflicted on Native Americans.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe of New Mexico whose grandparents and great-grandfather were taken from their homes and sent to boarding schools, launched the investigation three years ago, the first time the U.S. government had closely scrutinized the schools. As part of the investigation, she and Newland spent a year traveling the country and listening to stories of emotional, physical and sexual abuse told by survivors and their descendants.

“For so much of this country, boarding schools are places where affluent families send their children for an exclusive education. For Indigenous peoples, they serve as places of trauma and terror,” Haaland said Friday. “For 100 years, children as young as 4 years old were taken from their families and communities and forced into boarding schools run by the U.S. government and religious institutions. These federal Indian boarding schools have impacted every Indigenous person I know.”

At least 80 of the schools were operated by the Catholic church or its affiliates. The Post, in a yearlong investigation published in May, found evidence of rampant abuse of the Native American children under their care at 22 of these schools. At least 122 priests, sisters and brothers were later accused of sexually assaulting more than 1,000 children, with much of the abuse happening in the 1950s and 1960s.

Weeks after The Post’s report, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops apologized for inflicting a “history of trauma” on Native Americans.

In 2022, Pope Francis apologized for the church’s role in running boarding schools in Canada similar to those in the United States. He has not issued a similar apology for the abuse at Catholic-run Indian boarding schools in the United States.

Sam Torres, deputy chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said that Biden’s apology was “a very historic moment for Indian Country.” While most Native Americans are well-versed in the impacts and horrors of the Indian boarding school era, Torres said, “to hear that recognized by the president of the United States is truly empowering.”

“To hear him recognize the hurt, the pain and the lasting impacts of the federal government and Christian denominations working together to effectuate Indian boarding school policy,” Torres said, “was a commitment to expanding the truth.”