How WSU CB Ethan O’Connor built the tools to snag his pick-six — and how he ended up in Pullman to begin with

Washington State defensive back Ethan O’Connor looks back to celebrate after he intercepted a Fresno State pass and returned it for a touchdown during the second half Saturday in Fresno, Calif. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)

PULLMAN — Jason David knew he probably looked crazy. He was standing up and screaming in the middle of an Alo Yoga, a clothes store in southern California, waiting for his girlfriend to finish shopping, his voice echoing across the place.

It was last Saturday evening, a few minutes past 7 p.m., less than an hour until the store closed. Only a few customers still lingered. David paid them no mind as he yelled in celebration, looking down at his iPhone, which showed the reason for his party of one: His nephew, Washington State cornerback Ethan O’Connor, had just returned an interception 60 yards for a touchdown.

“I don’t know what she was trying on or what she was looking at,” David laughed. “I just had my head down on my phone.”

The visiting Cougars earned a 25-17 win over Fresno State in large part thanks to O’Connor, who leapt in front of a fourth-quarter pass for a pick-six, the first of his burgeoning career. Some 20 years ago, David himself had starred at cornerback for the Cougs, helping them win the 2002 Pac-10 title and totaling the second-most interceptions in program history.

But David had never experienced WSU success like this, watching his nephew stroll into the end zone for what turned into the game-winning pick-six, helping the Cougars secure their first 5-1 start since 2018.

“It’s interesting to see him just kinda come into his own,” said David, who went on to become a fourth-round NFL draft pick in 2004. “All the things that he and I have worked on, just seeing it come to fruition has been really, really cool, because I know how hard he’s worked. Things that we’ve talked about in the past, things that make a great player, so to see it all come together so early — it hasn’t been surprising, but it’s been very exciting.”

Through six games of his redshirt freshman campaign, O’Connor has generated several moments like it. He snagged his first career interception last month in WSU’s win over Texas Tech, and two weeks later against San Jose State, he grabbed another, picking off an overtime pass in the end zone. Heck, in Fresno, O’Connor would have finished with a pair of picks, but a penalty wiped out his first.

But not until he jumped the last pass and took it 60 yards the other way, David said, did O’Connor show off the latest improvements in his game: He used his IQ, remembering how Fresno State had run the same play twice earlier in the game, and he showed his willingness to take a risk and make a play.

Pride swelled in David when he watched O’Connor put those traits on display because he understood how much time the two had spent working on them. David resides in California’s Orange County, not far from where O’Connor grew up in Irvine, giving him chances to get together with O’Connor when he was in high school, putting him through all types of drills and lessons.

David was a shorter cornerback, around 5-foot-8, so the way he played is the way he trains defensive backs now: Eyes, angles and feet. O’Connor used his eyes to read FSU quarterback Mikey Keene, his feet to pedal to the spot and angles to put himself in a position to snag the interception and run straight for the end zone, never needing to adjust his route.

Put it all together and you get O’Connor the playmaker, the guy who isn’t just unafraid to make a play. He’s ready to roll the dice to do it.

“When I watch that, that’s what gets me so excited,” David said, “because he’s like, I’m gonna take this chance. I know it’s coming, and I’m gonna take a good angle to the ball. He got so far in front of (Keene), the guy had no chance of trying to run and catch him, because Ethan had took such a good angle. It was a perfect play.”

Not long after the game, O’Connor admitted something few players would: As this season unfolded, as he realized he would be starting for injured cornerback Jamorri Colson these first six games of the season, he felt nervous. “Super, extremely nervous,” he said. It wasn’t that he didn’t feel ready — it was that he was being pressed into action earlier than anyone expected.

His mom, Joni O’Connor, can always sense when her son is anxious on the field. In high school at Los Angeles-area Los Alamitos, he would stand with his legs crossed. When he walked, he would often side-step around. Now that Ethan is in college, his tells have changed: He’ll get soft in his shoulders. He’ll take deep breaths.

He’s never been nervous about his ability to make plays. “He’s always been a playmaker,” David said. What gets to him sometimes, Joni explained, is wondering how the play will end: Is a big play happening with me? Am I gonna be the one in charge of this big play? Am I gonna be the game-changer?

In that way, O’Connor walks a fine line like a trapeze artist, finding his balance over two conflicting realities: He oozes confidence on the field, knowing he has ball skills many cornerbacks don’t. He also wonders about his place in the WSU ecosystem at large, in this giant world of college football he’s still learning more about.

He sustained his confidence, his “thoroughbred” mentality in the words of Los Alamitos coach Ray Fenton, by picking up one of David’s habits on the field: Talking smack. He talks often, his mom said, which is what David was known for at WSU, making up for what he lacked in height with boisterous confidence.

O’Connor has been blessed with more size, but he might talk as much as his uncle did. After his second interception of the season, in overtime against San Jose State, he snagged the ball in the end zone, juked his way around a Spartan and pointed at him during the play. Against Fresno State, when he grabbed the pick that got called back, he also caught it in the end zone, then proceeded to look down at the FSU wideout, sharing some choice words before bolting away and surging some 50 yards downfield.

O’Connor showed his penchant for trash talk at such an early age that Joni began to worry. Off the field, Ethan was the nicest kid she knew, always has been. But between the lines, he was always ready to bark. In one 7-on-7 game, where David was the coach, Ethan got a flag thrown on him for talking too much.

David got on his nephew’s case. “What’s going on?” he asked him. “What’s with this attitude?

“It’s part of my game,” Ethan replied. “If I talk smack, I know I gotta back it up.”

“At that point, we both said, you know what, we can’t even take that from him,” Joni said. “He’s gonna smack talk, but afterwards he’s gonna shake hands. He’s gonna exchange jerseys, gloves, whatever that looks like. It’s literally from the first nap to the last snap, where Ethan’s being Ethan. But other than that, he’s having a good time.”

It’s the kind of confidence O’Connor leaned on back in August, when Colson sustained his injury and O’Connor understood he was next in line. He didn’t have time to wonder much anymore. Didn’t have time to process the nerves. After all, his name didn’t float to the top of the depth chart by accident. It’s no coincidence he’s found himself here, cashing in on his opportunity, giving his coaches something to think about now, even with Colson back in the fold.

No, O’Connor finds himself here in part because he was willing to see how he stacked up next to pros. In David’s training organization, Delta Sports Group, he often works with NFL cornerbacks, including the New York Jets’ DJ Reed, the New York Giants’ Adoree Jackson, the Houston Texans’ Desmond King II and the Washington Commanders’ Michael Davis, a southern California native like David.

In the summer of 2020, before O’Connor entered his sophomore year at Los Alamitos High, he decided he wanted to join some of those guys in workouts with David. Before he gave the green light, David offered advice to his nephew: Be seen more than you’re heard. Show up, do the work, and follow these guys’ lead.

A 16-year-old O’Connor was no match for the size and speed of NFL cornerbacks, of course, but he was never confused. Completed every drill. Technically sound. By the time the summer came to an end, David could sense that as O’Connor became more serious about playing at the next level, he had the tools to do it.

More importantly, David thought, O’Connor was ready to keep working to develop them. As a high schooler, O’Connor became friends with Mater Dei cornerback Zabien Brown, a five-star prospect who landed at Alabama. They started to work out together “all the time,” David said, signaling that O’Connor was capitalizing on his gifts, his 6-foot-1 frame, the connections he enjoyed thanks to his uncle.

Before long, O’Connor started to enjoy more than just connections. During his sophomore season, he fielded offers from LSU, Kansas and Arizona State, plus local powerhouses USC and UCLA. A few months later, the floodgates opened: Alabama. Georgia. Penn State. Texas A&M. As colleges recognized his potential, a rangy prospect who could play wide receiver or cornerback, a guy with speed and smarts, O’Connor could have gone most anywhere he liked.

When players get that kind of attention, David likes to say, one of two things tends to happen.

“You can start to feel yourself and say, OK I’m done working, I’m cool. I got all these offers, David said. “Or you can say, shoot, I’m a four-star. I wanna be a five-star. Like, I want to be the best. So he took the route of, I want to be the best. Like, these offers aren’t good enough.”

It wasn’t good enough for O’Connor. He proved it his senior year at Los Alamitos, where he blossomed into one of the Griffins’ top receivers and cornerbacks, playing both ways. For the season, he totaled 23 tackles, five pass breakups and two interceptions, plus 18 catches for 298 yards and five touchdowns on offense.

What Los Alamitos coaches remember most, though, is the way he changed and matured. As an underclassman, LAHS wide receivers coach Demar Bowe said, O’Connor felt confident enough to question some parts of coaching. By the time he made the varsity squad, he had already received a host of offers — so his thinking went something like, I know what I’m doing.

“As we went on, he kinda figured it out,” Bowe said. “Bumped his head a couple times, figured it out.”

To defensive coordinator Michael Cobleigh, O’Connor did a lot more than just figure it out. In Los Alamitos’ 2022 season finale, a blowout playoff loss to national powerhouse Mater Dei, some of the Griffins’ stars — the guys who had big-time offers, who had something to lose if they got injured — sat out of the game.

Not O’Connor.

“Ethan was battling down to the last play on offense and defense,” Cobleigh said. “That kid changed immensely. We knew that he had what it takes to make it in college at that point, because that last game against Mater Dei, No. 1 team in the country, he was balling out on both sides of the ball till the last whistle. We were down by, like, 50.”

By that point, O’Connor had already made a decision on his college home. He had committed to UCLA during his senior year. His path to Pullman, though, started to crystallize in Westwood.

***

In May 2022, five months before he committed to UCLA, O’Connor took his official visit to the Bruins. He took his mom, Joni, who spent her freshman year there running track. That was one of the bigger reasons Ethan found himself interested in UCLA.

He loved his visit. So did mom. Chip Kelly, then the Bruins’ head coach, knew everything about Ethan — “which I thought was super impressive as a coach,” Joni said. The program pulled out all the stops, showing Ethan all the resources the school offered, from facilities to nutrition to tutors.

“Everything a school could offer,” Joni said, “they had.”

What UCLA couldn’t offer, though, was a change of location. Ethan might have grown up in the Los Angeles area, but he’s anything but a city kid, Joni said. When Ethan was in junior high, Joni started taking him on camping trips to Kern County, north toward the Bakersfield area, where Ethan, Joni and friends went off the grid.

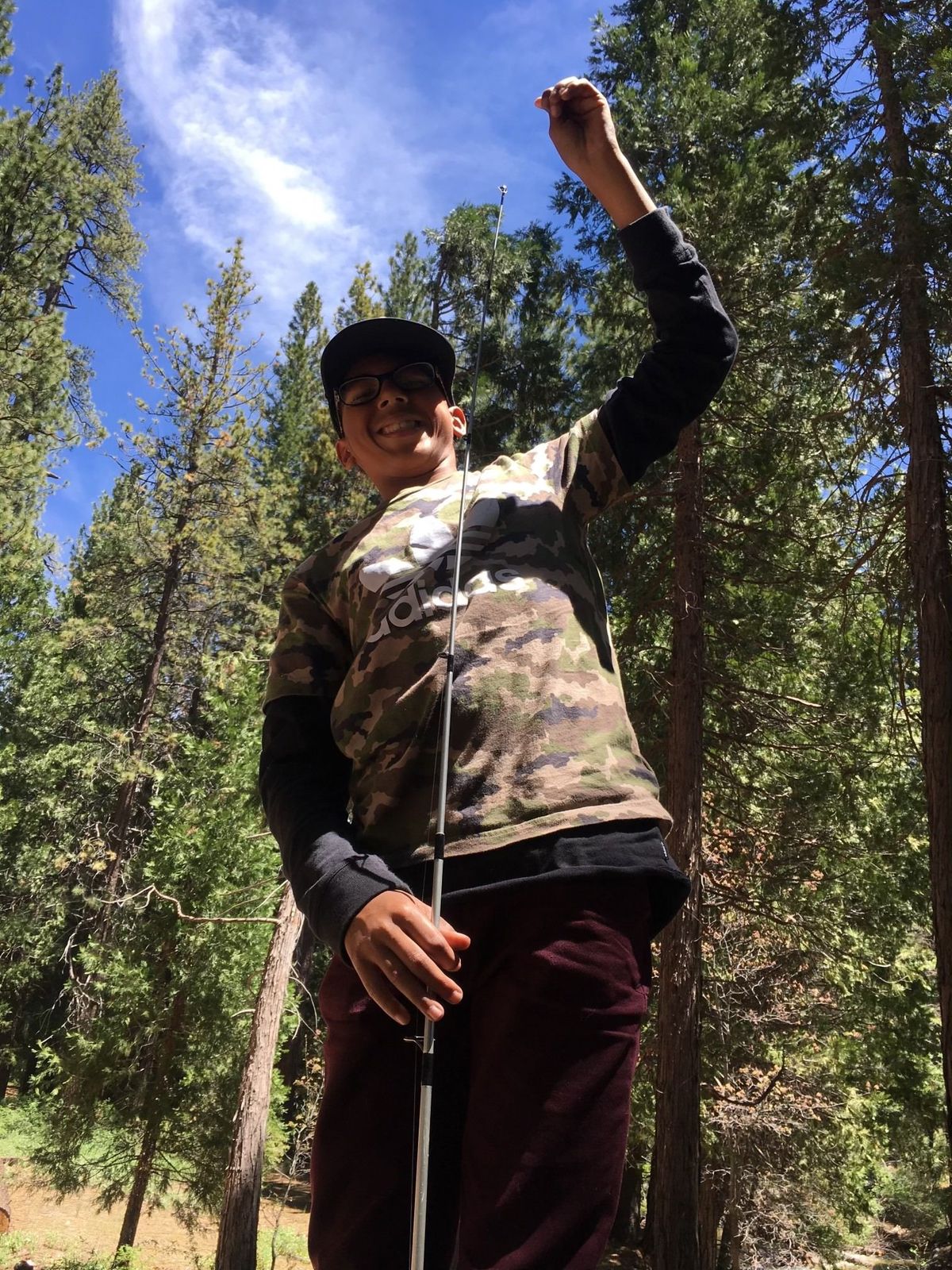

Ethan shot guns. Went fishing. Balanced on top of logs, looked down at the river, jumped in. Wearing glasses and looking skinny as ever, Ethan looked like he felt at home. To Joni, it confirmed what she already suspected about her son: He likes his peace. Wants to “check out,” in her own words.

“Don’t let the Jordans and the sandals and slides fool you,” Joni said. “He is definitely an outdoorsy kid.”

So in May 2023, about seven months after Ethan committed to UCLA, Joni had an extra bank of knowledge to draw on. That’s when UCLA officials began to communicate concern about Ethan’s grades in one class at Los Alamitos. He wasn’t failing anything, but with the Bruins’ high standards of admission, football staffers grew worried Ethan wouldn’t be able to get in.

So Joni got to thinking.

“I don’t want them to pull out and say, he got a C instead of a B, something like that. We just couldn’t risk it,” Joni said. “I didn’t want him to end up at a JC (junior college) That would have done, I think, a lot more damage on him personality wise.”

Joni and Ethan also didn’t want to sit pat, risking leaving the star cornerback with nowhere to go at all. So, mom figured, let’s re-open Ethan’s recruitment. Check back with some of Ethan’s previous offers, see if those are still on the table. In the summer of 2023, when they learned WSU still had a spot for him, mom and son decided to trek to Pullman.

They landed in Spokane, rented a car and hopped on US-195 headed south. Before long, when the Spokane pine trees turned into Palouse wheatfields, Ethan’s face lit up. Sitting in the passenger seat, he pulled out his phone, opened the camera app and aimed it out the window, snapping a picture of the rolling hills, which were brimming summer green and yellow.

About an hour later, they pulled into Pullman, stopping first at the intersection of NW Davis Way and Grand, the main drag through town. On the road in front of the stoplight was the WSU cougar logo, painted on the street in the signature crimson and gray.

Joni turned to her son.

“You know what that means?” Joni said. “This is a college town.”

“I think you can come here and run this town,” Joni continued. “I said, you can be a fan favorite. You can make the town love you. You can make your own history. You can do everything here. I said, these people in Pullman love their football team. There’s gonna be more people at the football game, and they’re gonna be people that even live here. And I said, that means a lot. I said it goes a long way.”

That, Joni could sense, resonated deeply with Ethan. When they arrived on campus and toured the Cougs’ facilities, Ethan saw his uncle’s pictures and stats on the walls. Jason David. At one point, Ethan turned to Joni with an amazed look on his face.

“He was like, I didn’t know my uncle was a guy,” Joni said. “I’m like, yeah, my brother was a guy.”

But David didn’t try to lure his nephew to Pullman. Only when David heard Ethan might be interested in WSU did he tell him about his time as a Coug. I had a good experience, David told him. Pullman’s cool. You’re winning. So if you think it’s a good fit, it’s a good fit.

Besides, Ethan realized later, he would rather build something at WSU than get plugged into something ready-made at UCLA. That made him a good fit, good enough to become a starter and snag a pick-six last weekend, sending his uncle into hysterics in a department store.