Trevor Noah on the power of imagination and his new book for children

It’s been two years since the Emmy-winning comedian and author Trevor Noah retired from hosting “The Daily Show.” Though he keeps his fan base informed of his thoughts on politics and culture via his weekly podcast, “What Now? With Trevor Noah,” he’s more distant from the rush of news than he once was.

Noah, who has no plans to jump back into that world before November, is taking a break from touring and filming to promote his new book: a timely all-ages fable about the power of imagination and how we choose to see the world around us.

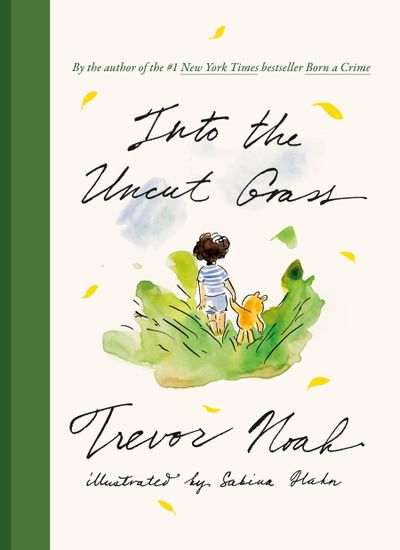

Featuring gorgeous illustrations by artist Sabina Hahn, “Into the Uncut Grass” finds Noah – already a best-selling author for his 2016 memoir, “Born a Crime” – sharing the tale of an unnamed boy and his talking teddy bear, Walter, as the two venture for the first time beyond the known world of their front door. He spoke with the Washington Post about the power of imagination, the chaos of American electoral politics and how young readers can learn to think differently.

This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q. In the introduction to “Into the Uncut Grass,” you write, “If imagination is the rocket, books are the rocket fuel.” What titles provided your reading rocket fuel as a child?

A. My elementary school teacher came to a show of mine in Germany recently, and she was telling me how one of my favorite books when I first started reading for myself was “James and the Giant Peach.” I think there was a series of books that (was) both fantastical and (which) took me into completely different worlds and ways of thinking that shaped a lot of my early, formative time as a reader. It was “The Chronicles of Narnia.”

And then there were a series of books that I’ve probably forgotten over time. Like the other day, I was thinking of a book like “The Wind in the Willows.” … It made such an impression on me when I was reading it as a kid. I promised myself I’d read it again.

Q. Did you have much access to Sunday comics as a child? I ask because something that came to mind while reading your book was “Calvin and Hobbes,” especially how it celebrates the potential of our imaginations and plays with a child’s concept of home and the unknown that exists beyond it.

A. I’ve actually never considered that. I grew up with my mom, and she wasn’t an avid newspaper reader, so I very seldom got newspapers. And I don’t think “Calvin and Hobbes” was as big in South Africa as it was on this side of the world. I remember we got “Garfield,” but “Calvin and Hobbes” was a relatively late addition to my world, so I never got into the lore of it all.

Q. I’d be remiss not to mention how integral and gorgeous the work of Sabina Hahn is. How did it feel when you first got to see some of the art intended for this project?

A. It’s been an absolute honor. To call Sabina an illustrator, I’ve learned, does her a disservice. If anything, she taught me that she writes with pictures. … Sabina has the ability to create the past, the present and the future in one still image, which is something I really, really, really took for granted before I got to work with somebody as skilled as her. The way she would take an image or a description of what we were trying to do and turn it into something that seemed like it had always existed in a fantastical way was something that I found myself continuously admiring and enjoying.

There was nothing too silly, nothing too ridiculous and nothing too out there for Sabina to draw or to think of drawing, and that really helped me to stay comfortable in a space that’s often uncomfortable for adults, and that is a place of fantasy and wonder and silliness.

Q. I imagine you’ve heard that “The Daily Show” won another Emmy, and that during the interviews that followed, Jon (Stewart) said he would welcome you back if you ever wanted to swing by. Do you ever miss it?

A. It’s funny. When I was getting ready to host during our election, that first election seemed like the most unhinged, and now unhinged seems to be the norm, unfortunately. I hope one day that’s not the case. It has been surreal, to be honest with you. It seems like a life that’s almost imagined, because it was part of my life every single day for almost eight years. I can’t explain to you how much of an honor it’s felt to think that I was part of that story and part of that legacy, to watch Jon Stewart and to know that I’ve been lucky enough to occupy that seat, and to still be able to chat with him. We laugh about things all the time. I’ll message him when something happens, and we’ll go back and forth. It’s an honor. It’s a joy. It’s a pleasure. It’s a privilege.

Q. You mentioned on your podcast that you watched the first – and perhaps only – presidential debate between Harris and Trump at 3 a.m. local time in the Netherlands. Was that surreal?

A. It’s an interesting and strange place to be – to realize that, more and more, America’s entire fate is going to be decided by a sliver of the country because of the electoral college. I don’t know how long that can last in a healthy way, but once again, the spotlight is on a few states. In my personal opinion, I just hope America finds a way to get out of the extreme partisan idea of what politics is. As I’ve spent more time out of the U.S. over the past few years, since leaving “The Daily Show,” I’ve come to realize that there is something that lies on the other side of believing that every issue is binary. I hope that America can slowly get back to that place, because I think it existed there for a while before all politics was national.

Q. That ties nicely back into your book, which touches on the limitations of binaries in several places, from the different patterned shells and opinions of the snails to the way the coins choose what they’re going to do for their recreational activities by flipping themselves and sticking to the results. It all speaks to the idea that concrete binaries can come with major limitations.

A. Yeah! That’s really one of the main things I was hoping the book could achieve: sparking a conversation among younger minds who have a more open perspective on how to see conflict. As we get older, I think we can take our idea of what should or shouldn’t be or how things should or shouldn’t be handled for granted. It becomes a little metastasized.

But when we’re young, if we’re taught very early, we can learn that there are many ways to see the world and many ways to engage with one another and many ways to broach an idea or a topic that we don’t agree with. As I tried to do in the book. The coins are really on a journey of asking the first question, which is: “What is the point of getting there if we get there alone?” And the snails are always looking for an opportunity to explore and see the world from an opposing point of view, even if they don’t agree, and then finding some of the merits in it. Then, of course, the gnome is asking the most important question, which is: How can you truly know if you are for or against somebody, or an idea, if you never actually get to know them in the first place?