As America’s marijuana use grows so do the harms

DENVER – APRIL 20: A man smokes a joint at a pro-marijuana “4/20” celebration in front of the state capitol building April 20, 2010 in Denver, Colorado. April 20th has become a de facto holiday for marijuana advocates, with large gatherings and ‘smoke outs’ in many parts of the United States. Colorado, one of 14 states to allow use of medical marijuana, has experienced an explosion in marijuana dispensaries, trade shows and related businesses in the last year as marijuana use has become more mainstream. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images) (John Moore)

In midcoast Maine, a pediatrician sees teenagers so dependent on cannabis that they consume it practically all day, every day – “a remarkably scary amount,” she said.

From Washington state to West Virginia, psychiatrists treat rising numbers of people whose use of the drug has brought on delusions, paranoia and other symptoms of psychosis.

And in the emergency departments of small community hospitals and large academic medical centers alike, physicians encounter patients with severe vomiting induced by the drug – a potentially devastating condition that once was rare but now, they say, is common. “Those patients look so sick,” said a doctor in Ohio, who described them “writhing around in pain.”

As marijuana legalization has accelerated across the country, doctors are contending with the effects of an explosion in the use of the drug and its intensity. A $33 billion industry has taken root, turning out an ever-expanding range of cannabis products so intoxicating, they bear little resemblance to the marijuana available a generation ago.

Tens of millions of Americans use the drug, for medical or recreational purposes – most of them without problems.

But with more people consuming more potent cannabis more often, a growing number, mostly chronic users, are enduring serious health consequences.

The accumulating harm is broader and more severe than previously reported. And gaps in state regulations, limited public health messaging and federal restraints on research have left many consumers, government officials and even medical practitioners in the dark about such outcomes.

Again and again, the New York Times found dangerous misconceptions.

Many users believe, for instance, that people cannot become addicted to cannabis. But millions do.

About 18 million people – nearly a third of all users ages 18 and up – have reported symptoms of cannabis use disorder, according to estimates from a unique data analysis conducted for the Times by a Columbia University public health researcher. That would mean they continue to use the drug despite significant negative effects on their lives. Of those, about 3 million people are considered addicted.

The estimates are based on responses to the 2022 U.S. national drug use survey from people who reported any cannabis consumption within the previous year. The results are especially stark among 18- to 25-year-olds: More than 4.5 million use the drug daily or near daily, according to the estimates, and 81% of those users meet the criteria for the disorder.

“That means almost everybody that uses it every day is reporting problems with it,” said Dr. Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, who was not involved in the analysis. “That is a very clear warning sign.”

Marijuana is known for soothing nausea. But for some users, it has the opposite effect.

Jennifer Macaluso, a hairdresser in Elgin, Illinois, turned to the drug in her 40s when a doctor suggested it to help her severe migraines. Starting in 2019, whenever she felt a headache coming on, she would take a hit of a marijuana vape pen and pop an edible from a medical cannabis dispensary. It worked.

But after several months, she developed stomachaches. A dispensary employee advised upping her intake, and eventually, she was using the drug nearly every day. Within months came episodes of nausea and vomiting so debilitating that she had to stop working.

About a dozen doctors misdiagnosed the problem. One removed her gallbladder, another her breast implants. Several chalked up her symptoms to menopause.

After searching online in 2022, Macaluso suspected she had cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, a condition caused by heavy cannabis use and marked by nausea, vomiting and pain. It can lead to extreme dehydration, seizures, kidney failure and cardiac arrest. In rare cases, it has caused deaths – at least eight in the United States, including some newly identified by the Times.

Since the syndrome was first documented in 2004, doctors say they have observed a sharp rise in cases. Because it is not recorded consistently in medical records, the condition is nearly impossible to track precisely. But researchers have estimated that as many as one-third of near-daily cannabis users in the United States could have symptoms of the syndrome, ranging from mild to severe. That works out to roughly 6 million people.

Eventually, a new physician confirmed Macaluso’s diagnosis, noting that new cases were coming in every week. “I was angry that doctors hadn’t caught it and that I suffered so much,” Macaluso said. She had continued to use the drug, she added, “because I thought it was helping.”

Meanwhile, as more people turn to marijuana for help with anxiety, depression and other mental health issues, few know that it can cause temporary psychosis and is increasingly associated with the development of chronic psychotic disorders.

Dr. Lauren Moran, a psychiatrist at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, is among the physicians who are seeing more cases of schizophrenia that they believe are linked to cannabis use. She said she emphasized to patients that “marijuana is a benign substance for most people, but it is also a risk factor.” She tells them, “The fact that you’re here shows that it is probably not benign for you.”

To assess the health risks of cannabis use, the Times examined medical records and public health and insurance data; reviewed scientific research; and interviewed more than 200 health officials, doctors, regulators and consumers. Reporters also surveyed more than 200 physicians in about a half-dozen specialties and almost 600 people who suffer from cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

Some of the ill effects have been reported in academic studies or news stories in recent years. The data and interviews reveal not only new, detailed evidence of the health risks but also growing alarm among doctors and researchers.

In interviews, they acknowledged that marijuana can offer substantial health benefits for certain patients. Most of them favored legalizing the drug. But many were concerned about significant gaps in knowledge of its effects, regulation of the commercial market and disclosure of the risks.

“Cannabis should not have a free pass as something that is safe because it’s legal – or safe because it’s natural – because actually, it clearly causes harm in a number of my patients,” said Dr. Scott Hadland, who oversees adolescent medicine at Mass General for Children and is an associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

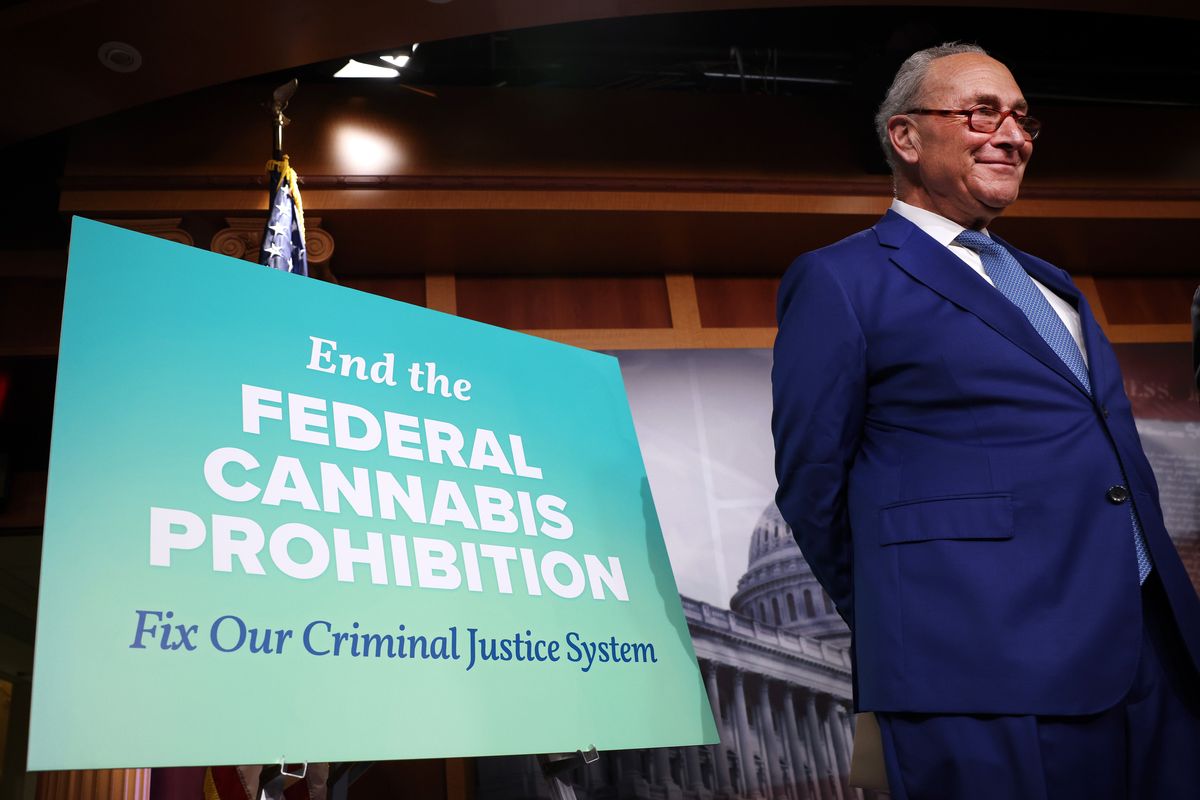

When states began legalizing marijuana nearly three decades ago, initially for medical use, they set in motion something of an unintended public health experiment. Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia now also allow recreational use of the drug, and after ballot measures this fall in Florida, South Dakota and North Dakota, it may be legal in more than half the country. Internationally, the United States is an outlier: Only a few countries allow such sales.

But cannabis remains illegal under federal law and classified as a tightly controlled substance, which has stymied oversight and scientific study. And states have rolled out inconsistent standards and other regulations, the Times found.

Only two states cap the levels of THC, the intoxicating component of the plant, across most of the recreational marijuana products sold in their jurisdictions. Only 10 require that those products come with warnings that cannabis can be habit-forming. Even fewer require warnings about cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome or psychosis. None are monitoring – or are even equipped to assess – the full scope of health outcomes.

“There is no other quote-unquote medicine in the history of our country where your doctor will say, ‘Go experiment and tell me what happens,’” said Carrie Bearden, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at UCLA.

In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine published a review of research on the health effects of cannabis and warned that the lack of evidence-based information posed a public health risk. Last month, the organization issued another report, criticizing the nation’s disjointed cannabis policies and calling for urgent action by the federal and state governments.

Yasmin Hurd, a neuroscientist and a leader on the report, said the medical field was falling behind in its understanding of the rapidly changing drug.

“Until we do research on the drastically transformed cannabis in all its forms, I think putting them under the umbrella of a safe, legal drug is wrong,” she said. “It’s misleading at best and dangerous at worst.”

Debilitating and undiagnosed

A telltale sign of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome is that heat often temporarily relieves the nausea and vomiting. Hundreds of people recounted to the Times, in interviews and survey responses, that they had spent hour after hour in hot baths and showers. Some were burned by scalding water. One teenager was injured when, in desperation, he pressed his body against a hot car.

Researchers don’t know why heat soothes the syndrome, known as CHS, nor why certain chronic marijuana users develop it and others don’t. But the onset appears to be related to the way marijuana interacts with the body’s endocannabinoid system, a network of signaling molecules and receptors that help regulate vital functions including sleep, digestion and the perception of pain. People with severe symptoms frequently require emergency care.

When Dr. Kennon Heard, an emergency physician at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, first heard of CHS, it took him by surprise. During his medical residency in the 1990s, he had been taught that cannabis-related issues were rarely seen in the emergency department. Now, he said, his hospital treats patients with the syndrome every day: “We started seeing it over and over and over again.”

Dr. Brittany Tayler, an internist and pediatrician at Hurley Medical Center in Michigan, said the center sees so many patients with it that staff members say to themselves, “’Here comes another one.’”

A 2018 survey of emergency department patients at Bellevue Hospital in New York found that among 18- to 49-year-olds who disclosed consuming cannabis at least 20 times a month, one-third met criteria for the syndrome. Based on those rates, the researchers estimate that today, about 6 million near-daily marijuana users in the United States could have symptoms of CHS.

The emergence of the syndrome over the last two decades coincides with the spread of marijuana legalization in the United States.

Lawmakers and voters began legalizing medical marijuana state by state in the 1990s, moved by testimonials from AIDS and cancer patients who said it relieved their suffering and from doctors describing its therapeutic effects.

The subsequent push to allow recreational use, particularly in Democratic-leaning states, was fueled in part by growing resistance to policies that incarcerated a disproportionate number of Black people for minor marijuana offenses. Proponents also argued that a regulated market would be safer and generate tax revenue.

The commercial industry that followed touted its products as beneficial while focusing not on developing marijuana’s medical uses but on engineering a quicker, more intense high.

The marijuana smoked in the 1990s, typically containing about 5% THC, was transformed. Companies turned out inconspicuous vape pens, fast-acting edibles, prerolled joints infused with potency enhancers and concentrates with as much as 99% THC. (These are different from concentrates of CBD, a nonintoxicating component of the cannabis plant that is also widely seen as therapeutic and has gained in popularity.)

The commercial market expanded further in 2018 when Congress legalized hemp, a cannabis plant used in industrial products, and inadvertently legalized highly intoxicating hemp-derived compounds like Delta-8 THC.

As new products emerged – both at legal dispensaries and on the illicit market – and hospitals around the country saw influxes of CHS, researchers called for public health messaging about the syndrome and more education for medical providers. But awareness was slow to spread.

One impediment is the lack of a specific diagnostic code for the syndrome in the system used by medical providers in the United States, which has made tracking the condition challenging.

The codes that do exist don’t precisely capture all of cannabis’s ill effects. For instance, cannabis-related diagnoses jumped by more than 50% nationwide between 2016 and 2022 – from about 341,000 people to 522,000 – according to data from the nonprofit Health Care Cost Institute on patients younger than 65 with employer-paid insurance. But those numbers are almost certainly undercounts, the organization said.

Most states that have legalized marijuana do not even mention CHS on their public health websites. And the industry at large has not addressed the syndrome.

When Alice Moon, 35, a prominent cannabis marketer, was diagnosed in 2018, she tried to educate colleagues at conferences and in published articles. The responses, she said, ranged from dismissive to hostile.

“I’ve gotten a lot of hate,” Moon said. “I’ve been bullied. People in the industry say I’m a Big Pharma plant.”

Most of the roughly 600 people with CHS who responded to the Times survey said they had been disbelieved by colleagues, friends or relatives, or accused of trying to sabotage marijuana legalization.

Many of the respondents, who are in a Facebook support group, said they had begun consuming the drug as teens, to self-medicate for anxiety or depression or just to have fun, and eventually escalated to using THC concentrates or other high-potency products multiple times a day.

Like Macaluso, the hairdresser, many reported that they had sought medical help for months, even years, before finally getting a correct diagnosis. Some likewise had unnecessary surgeries. Many said they felt the medical system had failed them.

Mecca Irby started smoking marijuana at age 15. Soon, she was vaping concentrates with more than 90% THC many times a day. She has struggled with anxiety and depression and found that the drug “was able to just give me a little bit of peace.”

But on her 18th birthday, she woke up with a horrible stomachache, started throwing up and couldn’t stop. Two days in a row, her father took her to a hospital, where she was stabilized and sent home without a diagnosis. It wasn’t until a couple of months later that a doctor at another hospital told her she had CHS, news that was hard for her to accept.

“This has helped me through so much stuff; this cannot be something that could potentially kill me,” Irby, who is 19 and lives in the Seattle area, recalled thinking.

She was able to do the one thing that cures the syndrome: quit cannabis. But not everyone can.

Among the fatalities identified by the Times was Kevin Doohan, a 37-year-old electrician in California with a fiancee and a young daughter. He died in 2020 after living with CHS for a decade.

He had stopped going to hospitals when symptoms hit because he didn’t want to be far from hot baths, according to his mother, Kim Holdredge. But during that last cycle of illness, bathing and passing out, he never woke up.

Holdredge said she had to explain CHS to the medical examiner so that it would correctly be listed as the primary cause of death.

“They’d never heard of it,” she said.

In recent years, the syndrome has received growing attention in the medical field. Among those who speak out about it is Dr. Ethan Russo, a neurologist in Vashon, Washington, who helped develop one of the few cannabis-derived drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and continues to research therapeutic benefits of marijuana.

“I spent most of the last 30 years supporting medicinal uses of cannabis,” he said. “However, I have also talked about the harms and pitfalls of cannabis, specifically cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. It’s a serious problem and a genuine reason that some people should not use.”

‘Like he was possessed’

Dr. Sharon Levy, chief of addiction medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, had a patient who believed coat hangers and sneakers had come to life. Dr. Luke Archibald, an addiction psychiatrist at Dartmouth Health in Lebanon, New Hampshire, treated one who was charged with trespassing after following the directions of voices he hallucinated.

Many physicians said that they have seen growing numbers of patients with cannabis-induced temporary psychosis – lasting hours, days or even months. While it is more common among younger consumers, it can afflict people of all ages, whether heavy or first-time users, and with or without a family history or other risk factors for psychosis.

Levy and other physicians have also seen a rise in chronic psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, in which they believe cannabis was a contributing factor.

Marijuana use can affect brain development, particularly during the critical period of adolescence through age 25. This is also the period when psychotic disorders typically emerge, and there’s growing evidence associating the two. Recent studies show that the more potent the cannabis, the more frequent the use and the earlier the age of consumption, the greater the risk.

“Not everyone who smokes cigarettes develops lung cancer, and not everyone who has lung cancer smoked cigarettes,” said Dr. Deepak Cyril D’Souza, a professor at Yale School of Medicine and a staff psychiatrist at VA Connecticut Healthcare Systems. “But we now know, after denying it for many, many decades, that the association between the two is very important. The same is true for cannabis and psychosis.”

While chronic psychotic disorders are rare, affecting 1% to 3% of the population, they are among the most debilitating mental illnesses.

A study in 11 sites across Europe found that people who regularly consumed marijuana with at least 10% THC were nearly five times as likely to develop a psychotic disorder as those who never used it. A study in Ontario found that the risk of developing one was 11 times as high for teenage users compared with nonusers. And researchers estimated that as many as 30% of cases of schizophrenia among men in Denmark ages 21 to 30 could be attributed to cannabis use disorder.

“It’s not clearly causal at this point, but there are a lot of facts that are known at this point about the relationship,” said Bearden of UCLA, who led a recent systematic review of studies of cannabis and chronic psychosis.

Bearden, who supervises a clinic for 12- to 25-year-olds in whom schizophrenia is starting to surface, estimates that when it opened 20 years ago, about 10% of the patients used marijuana regularly. Now, she estimates, nearly 70% do.

Patients tell her cannabis calms them down and offers temporary relief. She believes that may be true, but also that heavy use of the drug is contributing to their underlying illness and compromising their treatment, a perspective shared by others in the profession.

“Could I say that this person would never have developed these symptoms were it not for their cannabis use?” Bearden said. “Not with certainty. But I feel very confident that it is not helping, and it’s probably making things worse.”

Javonte Hill said he had no idea the drug was linked to psychosis until he took a bong hit of cannabis flower from a Denver dispensary last year. Hill, a soft-spoken Navy veteran, had been diagnosed with PTSD, anxiety and depression before leaving the service but had not sought treatment. His girlfriend, Eva Zamora, used marijuana occasionally and told him it was a good way to chill out. A bite of an edible several days earlier made him feel agitated. A dispensary worker offered another product, saying it would be more relaxing.

But Hill was quickly overwhelmed with dread, paranoia and hallucinations. An hour or so into the psychotic episode, as their two dogs started fighting, he went upstairs, retrieved his gun and started shooting, injuring Zamora and killing one of the pets.

“It was like reality dissolved in front of me. I was seeing depictions of the devil in hell and demons,” said Hill, 33. He was diagnosed with drug-induced hallucinations, medical records show, and is on probation after pleading guilty to animal cruelty and assault charges. He is suing the dispensary chain, claiming it failed to warn him about the risk of psychosis.

Zamora, 26, said it was terrifying to watch the temporary transformation of Hill, who has had no other episodes. “It was almost like he was possessed,” she said.

Alyssa Houlihan was also unaware of the risk when she began vaping cannabis as a high school student in Southbury, Connecticut. Her mother, Lisa Ross, wasn’t worried. She recalled smoking joints in her youth and thought the drug posed no danger to her daughter, an A student and volleyball player.

But in 2019, early in her junior year, Houlihan lost her grip on reality. She started hearing voices and was consumed with other delusions. It took four months in a hospital for her to stabilize and another 18 months to fully recover.

When a psychiatrist suggested that the cannabis had caused her symptoms, the family was devastated. Houlihan, now 23 and a nursing student, has not experienced any more psychosis. But, she said, “it robbed me of my teenage years.”

Can’t eat, can’t sleep, can’t focus

Even without psychosis or CHS, cannabis can disrupt lives.

While the drug can assist the endocannabinoid system, alleviate some symptoms of disease and otherwise make people feel good, regular heavy doses of it can also throw the system off balance. People must continue escalating their use to get the same effect. And quitting can cause anxiety, depression and other signs of withdrawal.

“You don’t want to shut down the system that controls your well-being,” said Dr. Bonni Goldstein, who runs a medical cannabis practice in Los Angeles.

Nathanael Katz, 21, is among hundreds of users ranging in age from teens to 70s who told the Times they had struggled with cannabis addiction. He began using marijuana at 12, when a cousin handed him a joint at a family gathering. By 13, he was consuming all day, every day, alternating between joints and vapes, which he could use without detection at his Manhattan school.

For a while, he liked how it eased his anxiety. He felt more relaxed in class and while talking to girls. But as his tolerance grew and his use increased, he started feeling more anxious, more introverted. It was hard to concentrate on homework, and he couldn’t sleep or eat without cannabis.

“That’s why I really knew it was a problem, because I was like, ‘I don’t like how it makes me feel,’ but I would still do it constantly,” Katz said. He eventually used opioids as well and ended up in rehab. Now 14 months sober, he coaches teenagers seeking to quit drugs.

People are considered to have cannabis use disorder if they meet two of 11 criteria, which include craving the drug, building up tolerance and continuing to use it even when it interferes with work and social activities. People who meet six criteria are considered addicted.

Last year, the federal government’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the rate of cannabis use disorder among people ages 18 to 25 was 16.6%. It has caught up to the rate of alcohol use disorder, 15.1%.

“It’s a really significant turning point,” said Deborah Hasin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University who performed the unique analysis of other data from the survey for the Times.

Those ages 12 to 17 have not shown notable increases in cannabis use in the survey, but their rate of cannabis use disorder is ticking up, and it’s higher than their rate of alcohol use disorder (5% compared with 3%). Like alcohol, recreational marijuana is illegal for those younger than 21.

Dr. Deb Hagler, a pediatrician working with a largely rural community in Maine, sees teens and young adults whose chronic use makes them miss out on important developmental markers like getting a driver’s license or holding a job – “all these little failure-to-launch things,” she said.

Quitting marijuana can be rocky. People with CHS typically experience the most difficulties, including physical pain similar to withdrawal from harder drugs, but others also struggle to eat, sleep and otherwise function. People who turned to the drug to help ease anxiety or depression find that those underlying issues worsen at first without the cannabis.

While opioid users can get some relief with medicines to help break their addiction, there are no FDA-approved drugs to help people quit marijuana.

Ziva Cooper, director of the UCLA Center for Cannabis and Cannabinoids, is seeking funding to study withdrawal from the increasingly popular THC concentrates. Previous studies on withdrawal were done with cannabis containing 3% to 7% THC, making them significantly outdated.

“What we’re talking about now, what people are using, is a whole other beast,” she said.

‘People need to know’

In its long, fraught relationship with marijuana, America has by turns praised and feared the drug, revered its coolness, locked up those who sold it and warned children to say no.

Now, state by state in this new age of cannabis, growing numbers of doctors and consumers say that there is an urgent need to balance easy legal access to the drug with better protection for the public.

Some efforts are underway. The Biden administration, for example, is seeking to move cannabis into a less restrictive category of drugs, which would allow more research into its health benefits and risks. And a federal law that took effect last year aims to ease other barriers to scientific study.

Some medical specialty groups are issuing guidelines for treating cannabis-related ailments. And the CDC says there are plans to roll out a distinct diagnostic code for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome late next year, which could help determine the scope of such cases.

Still, many people interviewed or surveyed by the Times said that much more was needed to identify, track and address harms. “We as scientists have done a really bad job in educating the general public,” said D’Souza, the Yale psychiatrist.

Macaluso, the hairdresser in Illinois, said if she had known that cannabis could cause such suffering, she would not have kept using the drug after her symptoms started – let alone increased her intake.

“My biggest thing is: People need to know,” she said. “They’ve just got to be warned.”

______

Methodology

Deborah Hasin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, analyzed data from the federal government’s annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health to calculate rates of cannabis use disorder among self-identified cannabis users. Rates were determined for various age groups and for different types of users – those who had consumed cannabis at all in the previous year, and those who had consumed it almost daily. (The latter includes respondents who reported that in the previous year, they had used the drug 240+ days, an average of 20+ days per month, or an average of 5-plus days per week.)

Cannabis use disorder is measured with 11 criteria, which are also used to determine severity: Meeting 2-3 criteria is considered a “mild” disorder, 4-5 “moderate” and 6 or more “severe.” The survey includes questions corresponding to the criteria. Hasin used data from the 2022 survey, the most recent year for which detailed records are available.

Separately, the New York Times emailed a survey about cannabis-related risks, benefits and health issues to more than 8,000 doctors in about a half-dozen specialties at medical teaching programs across the country. Several medical associations also agreed to distribute it to members. More than 200 doctors shared their experiences treating patients who used cannabis, their observations on the prevalence of cannabis-related health issues among their patients, the extent of their training on cannabis’s risks and benefits, and challenges in diagnosing problems.

The Times posted a different survey, with detailed questions about personal experiences with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, in a popular Facebook group with more than 28,000 members for people with the condition. About 600 people responded.

Reporters interviewed dozens of respondents to both surveys. The Times survey results were not used to calculate the estimates of cannabis consumption or cannabis use disorder cited in this article.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.