A pianist, a shaman, a pacifist: Faces of the suffering in Putin’s prisons

Russia is locking up its finest.

A brilliant concert pianist, an outspoken crane-operator, a poet, a historian, a self-proclaimed shaman, and hundreds of bloggers, pensioners, activists and journalists have been imprisoned for defying President Vladimir Putin’s rule.

Some have died in prison in murky circumstances, including opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Some are seriously ill and denied medical treatment. Some have been tortured or raped. Dozens have suffered forced psychiatric incarceration reminiscent of Soviet times.

An August prisoner exchange freed a number of Russia’s most prominent political prisoners, but more than 1,300 remain in custody, according to Mariana Katzarova, U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Russia. A similar exchange in the future is unlikely, with Western pressure focused largely on foreign prisoners.

A report by the United Nations on Sept. 24 stated that Russians were being given “shockingly long sentences on absurd grounds” – such as reading a poem, saying a prayer, producing a play or posting on social media. “The country is now driven by a state-sponsored system of fear and punishment, including the use of torture with absolute impunity,” Katzarova said.

This punitive approach to political prisoners, including bullying and extended solitary punishment, appears designed to break them and deter others from even the mildest dissent, according to activists.

Vladimir Kara-Murza, an opposition leader and Washington Post columnist who was freed in the August exchange, said at a Sept. 23 gathering of the Global Magnitsky Justice Campaign in London held to celebrate his release, “I wake up every morning and every night thinking of all those who are still left behind. For many of them … it’s not just a question of their unjust imprisonment, although that would be unacceptable in itself, but it’s also a question of life and death.”

The situation is only getting worse, said Olga Romanova, founder of the prisoners’ rights group Russia Behind Bars, noting that the prison officials responsible for Navalny’s death were promoted. “It’s a different reality now. Just torture political prisoners and you’ll be fine,” Romanova said.

Romanova lauded those who refuse to stay silent in the face of their government’s repression. “These are people with an acute feeling of justice,” she added. “They’re people who are inconvenient for society. We all remember when we were teenagers and we had this fire, a sort of madness within ourselves.”

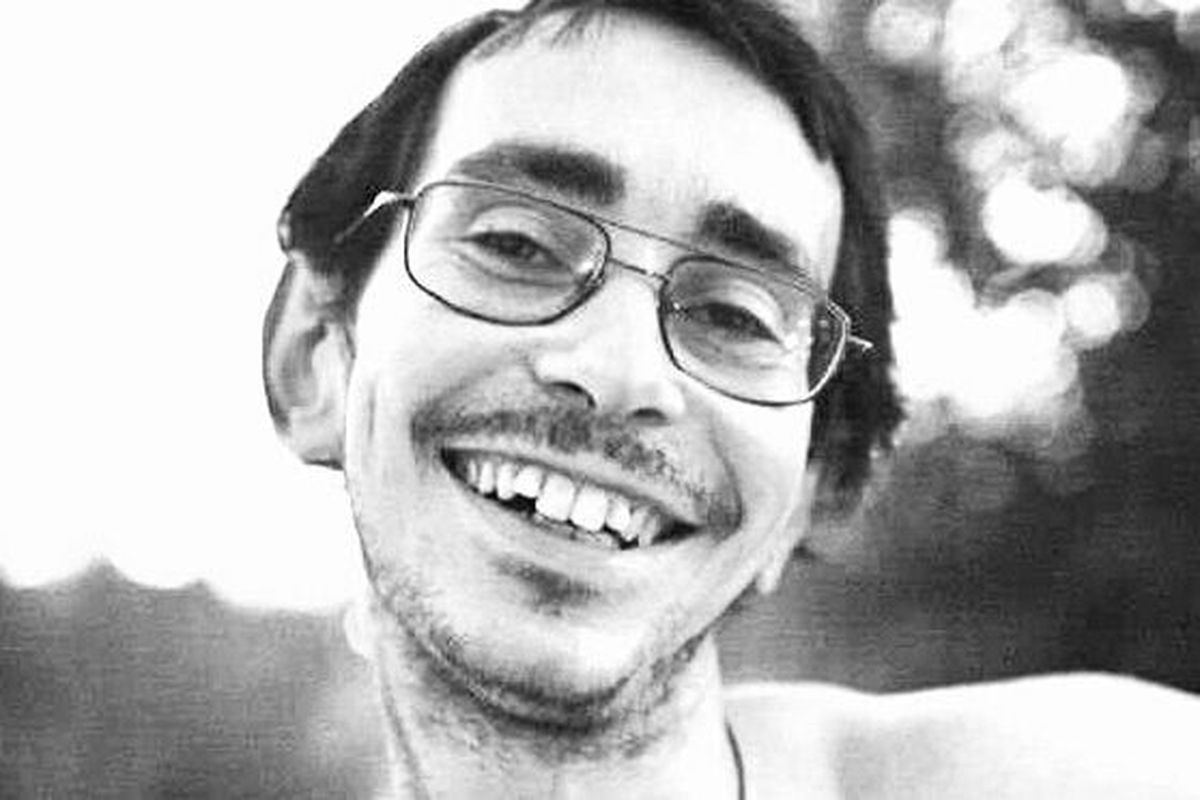

The pianist

The case of Pavel Kushnir, a young concert pianist who died in custody while on a hunger strike, has garnered particular attention. The solo pianist with the Birobidzhan Symphony Orchestra in eastern Russia was jailed after posting a 50-second video titled “Life” on Jan. 5 on his YouTube channel, which had only five subscribers.

“Life is something that can never be under fascism. Freedom, creativity, love, sincerity, truth, the tragic beauty of the human face,” he said in the video. “Down with the war in Ukraine, down with Putin’s fascist regime. Freedom for all political prisoners!”

Kushnir was arrested in May and charged with inciting terrorism. He went on a hunger strike in prison and died in late July. Many learned of his talent only after his death. Eleven people attended his August funeral, none of them family.

Grace Chatto, a British cellist with the group Clean Bandit, studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Kushnir in 2004 and called him “an incredibly special person and an incredibly special musician.” She lived in the student dormitory, where she listened to Kushnir and other brilliant pianists give impromptu concerts in their fourth-floor room until dawn.

“He just played with such a passionate and unusual style, with so much rubato,” she said, referring to a nuanced, expressive technique. “He’d play all of the Shostakovich preludes. And … there’s only a handful of people in the world who can do that from memory.

“And it’s so heartbreaking that people are only hearing his performances in a wider sense across the world now.”

Kushnir recalled those student days in an interview with Birobidzhan state television in January last year. In it, he declared that “true art can take place in a dorm room.”

“At five in the morning in the presence of two bums from Sadovaya, in a room full of drunken bodies, you can play Debussy’s preludes brilliantly on a keyboard doused with alcohol and set on fire, and see the tears in the bums’ eyes.”

The son of music teachers, he began playing at 2. Olga Shkrygunova, a Berlin-based Russian pianist who knew him since early childhood, said he eschewed the possibility of a great career because of his artistic integrity and dislike of grasping ambition.

“Pasha was a genius,” she said, using his nickname. “He was unique. He was a very strong person morally. He was never afraid of anything.”

The shaman

For two years, Alexander Gabyshev, a self-described “warrior shaman” from the Sakha republic in the Russian Far East, attempted to march thousands of miles across the country to Moscow, gaining an online following in the process.

His plan was to carry out a fire ceremony in Red Square that he said would cause Putin to resign.

But he was intercepted by several dozen masked special police officers near Lake Baikal in the Buryatia republic and in 2021 was forcibly committed to a psychiatric institution, after doctors reported that he suffered from “delusional ideas of reform.”

His attorney, Alexei Pryanishnikov, said his client was subjected to “punitive psychiatry” and described how Gabyshev begged at his trial to be sent to jail rather than back to the secure psychiatric institution.

At one point, he was so drugged that he passed out during a court hearing, Pryanishnikov told the independent Russian outlet Bereg.

The activist crane operator

Rafael Shepelev also was confined to a psychiatric institution for having ideas about reform. The longtime Yekaterinburg activist, crane operator and vegan had been previously arrested and jailed for protests and was featured in the documentary film “The Last Relic.” He escaped to Tbilisi, Georgia, in 2021 but, according to activists, was lured to a Russian military base in October, before being arrested and charged with terrorism.

In April, a commission at the Sverdlovsk Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital declared he had a chronic psychiatric disorder and could not understand the “social danger of his actions.” It confined him indefinitely to a secure psychiatric facility in the Sverdlovsk region.

Daniil Shepelev, his son, told Bereg that “if he speaks about opposition, they inject him with something” that makes him sluggish. Now his father no longer discussed his opinions for fear of being drugged, the son said.

Citing court records, Bereg reported at least 86 similar political cases.

“Raphael is a very honest and open and sincere person,” an activist friend in Yekaterinburg said in a phone interview, speaking on the condition of anonymity for security reasons. “I’ve never met anyone like him. He always tried to talk to people, to educate them. He wanted people to know about the situation in the country.”

The pacifist

Alexander Demidenko “always wanted to do heroic deeds,” according to his son, Oleg, who lives in the Czech Republic. “Such stubbornness, high self-esteem and high self-belief helped my father to do everything he did.”

Demidenko, a trained rocket engineer who lived in the Belgorod region bordering Ukraine, was a committed pacifist and worked as a geography teacher and textbook salesman. He helped around 1,000 Ukrainians stuck in Russia get home after their country was invaded by Putin in February 2022, according a volunteer who worked with him.

“He believed in the law. He believed in right and wrong,” said the volunteer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid persecution by Russian authorities. “But we always had the impression something bad would happen to him. He was arguing with the administration, trying to improve conditions for the refugees on the border.”

Demidenko was detained last year and tortured by the Akhmat special forces, a Chechen unit operating in the region, the volunteer said. He was charged with possession of an old hand grenade but later learned that he also faced treason charges. In April, authorities announced that he had killed himself.

His son is skeptical that it was suicide. There were scratches on his father’s face, a bruise near his ear, and the body was not autopsied, Oleg said.

A Russian human rights project, Faces, has highlighted 16 other urgent cases – such as those of historian Yury Dmitriev, of the banned rights group Memorial, who has been imprisoned for 15 years on child abuse charges that Faces calls trumped-up after he exposed mass graves of the victims of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin; and Artyom Kamardin, a poet and mechanical engineer, who was arrested for reading an antiwar poem and, according to the group, brutally raped by law enforcement officials.

“You cannot mention every name,” Kara-Murza said, “because it would take up an entire day.”