The 10 best graphic novels of 2024

(Drawn and Quarterly)

Comics are famously adept at visibly rendering the mechanics of time. Many of the best graphic novels of 2024 revel in that very capacity, dwelling on the way stories move between generations, how we recall childhood and even on the inhuman cadence of rivers. These 10 books differ wildly in style and content, capturing the remarkable range and diversity of the medium.

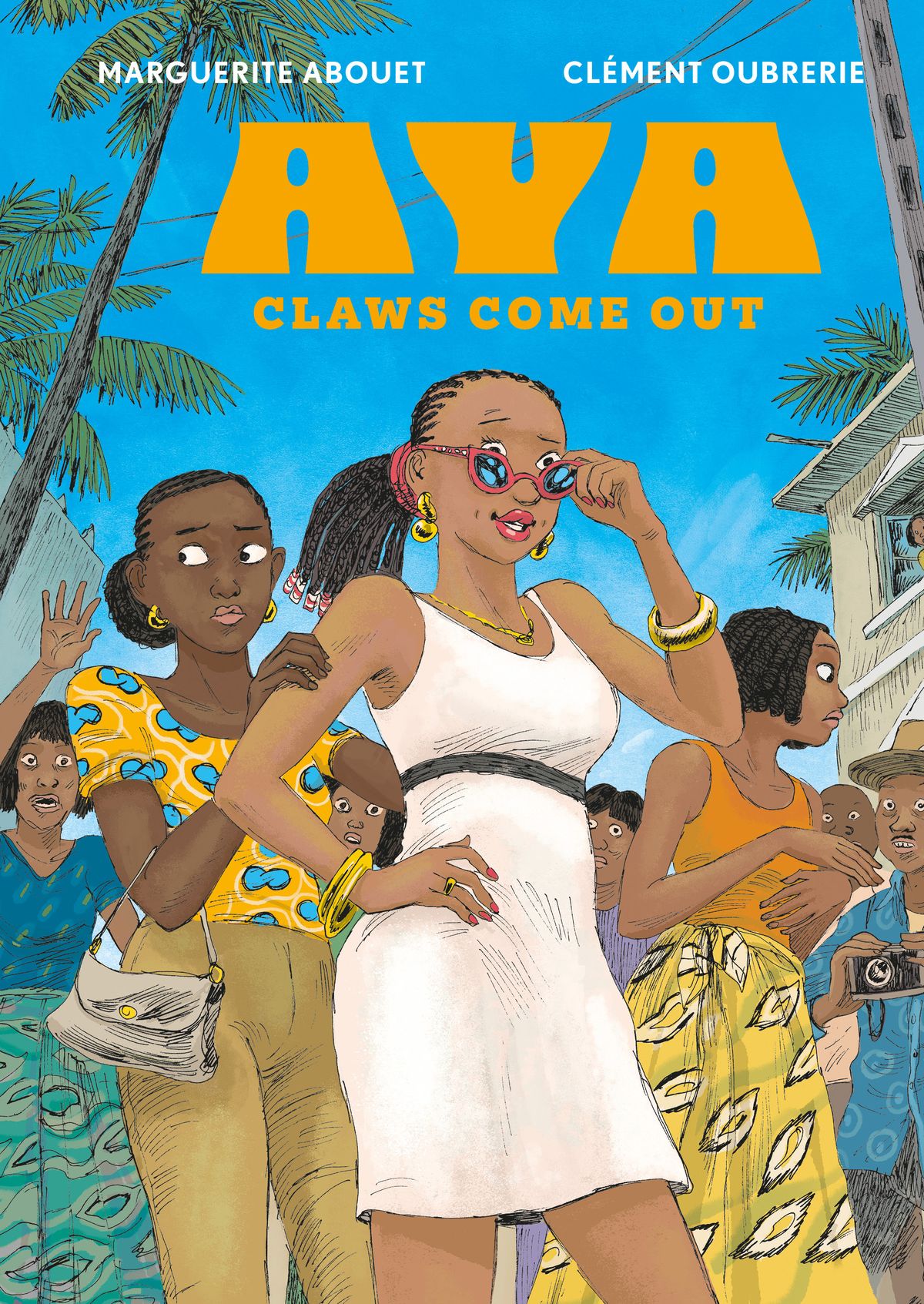

1. ‘Aya: Claws Come Out’ by Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie, translated from French by Edwige Renée Dro

The latest installment in Abouet and Oubrerie’s long-running series about life in Ivory Coast finds the huge cast awash in delightfully soapy situations. For one character – who has become the controversial star of a popular TV show – the soap-operatic quality of it all gets a little too literal. But in Aya’s world, everyone is busily in everyone else’s business, whether they’re dealing with bad bosses, struggling with their sexuality or running from the police. With an energetic visual style, the book bounces from human drama to human drama, maintaining a pronounced sense of delight even when it takes up weightier issues.

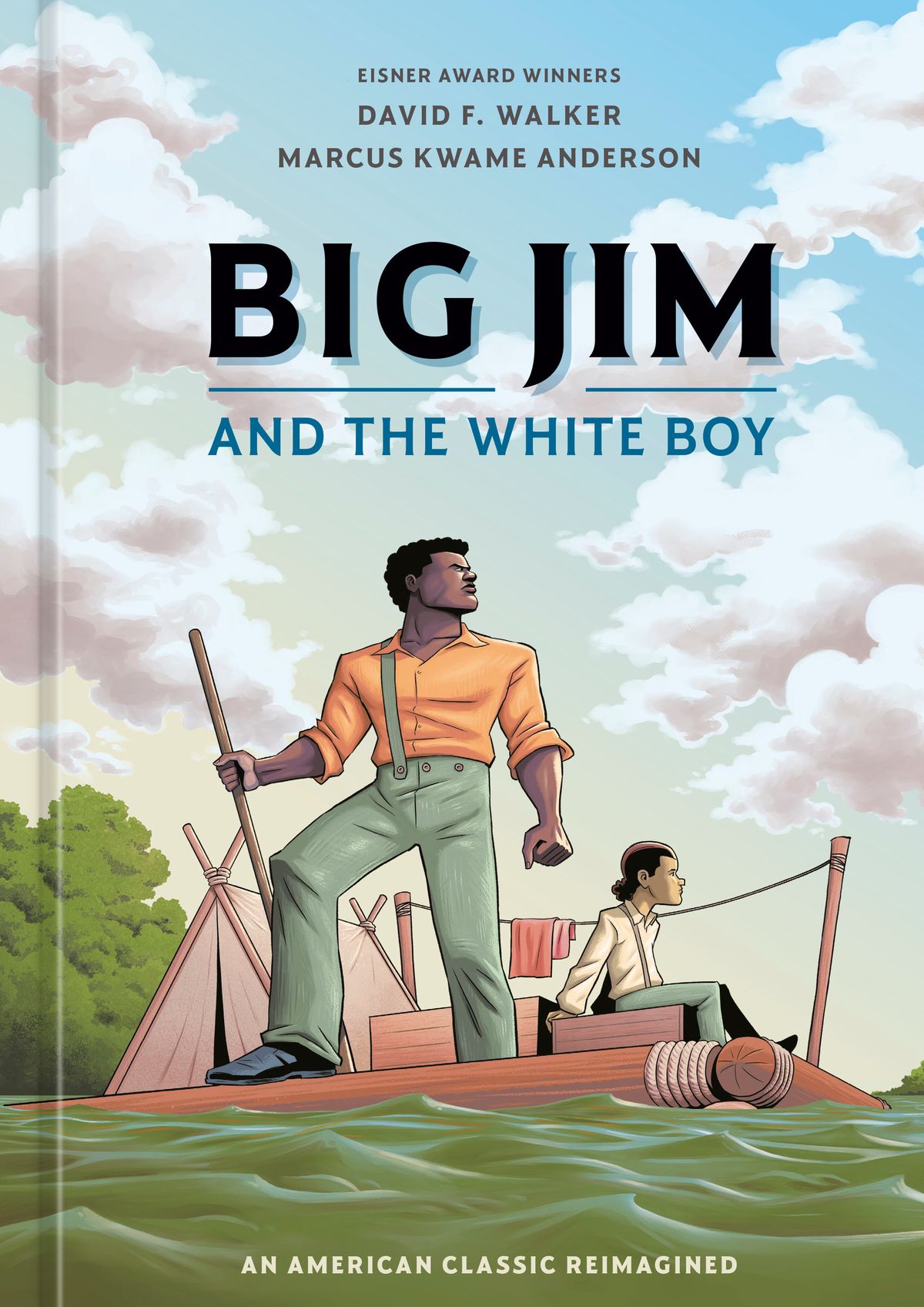

2. ‘Big Jim and the White Boy’ by David F. Walker and Marcus Kwame Anderson

In the year of Percival Everett’s “James,” did we really need another retelling of “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”? Walker and Anderson answer with a resounding yes in this stirring book that radically reworks the racial politics of Twain’s novel, turning its heroes into antislavery crusaders and rethinking the bonds of kinship that connect them. Perhaps most powerfully, it stretches forward, investigating the story’s reverberations more than a century on in a way that leaves readers with a moving meditation on familial inheritances and the power of shared stories.

3. ‘Blurry’ by Dash Shaw

In this matryoshka of a novel, we follow mostly ordinary people as they struggle to make decisions great and small – from what shirt to buy to who they want to love. At the end of each episode, an encounter with a friend or stranger leads to the next story, and Shaw slowly knits together tales of discrete lives. Drawn in a spare and precise style, “Blurry” cuts through the fog of our alienated era, inviting us to acknowledge the sometimes subtle connections that bind us to one another.

4. ‘Final Cut’ by Charles Burns

Burns is best known for his more fantastical stories, but “Final Cut” finds him working in a realistic, almost autobiographical key as he follows a group of young people making an amateur monster movie. In the process, he maps the entangled fate of creative and romantic disappointment, vividly imagining just how hard it can be to do justice to the stories that unfold in your head. Meanwhile, his own art, with its sharp border lines and tightly contained tracts of ink, is as precise and compelling as it has ever been.

5. ‘French Girl’ by Jesse Lee Kercheval

Not quite a memoir and not quite fiction, “French Girl” consists of vignettes drawn from Kercheval’s childhood, stories that obey the sidewise logic of dreams more often than they do the mechanics of memory. Here she takes us through a house full of clocks into a nocturnal forest, where she meets a wolf that protects instead of menaces. Her visual style is willfully rough, her prose simple, but the effect is as rich and evocative as a youthful summer.

6. ‘The Puerto Rican War: A Graphic History’ by John Vasquez Mejias

Working in stark black-and-white woodcut prints, “The Puerto Rican War” explores a largely forgotten episode in U.S. history: an armed insurgency in Puerto Rico in 1950 that was tangled up with a plot to assassinate President Harry S. Truman. The book’s visual style puts the literal grain of Mejias’s work on display, a testament to just how difficult some stories can be to tell – and how important they can be to rediscover.

7. ‘Spiral and Other Stories’ by Aidan Koch

Drawing and painting with a voluptuous minimalism, Koch sets little moments of human longing and wondering against the deeper and slower time of rivers, hills and forests. The book’s short fictions are enigmatic – an artist takes a long bus journey, two friends discuss a New Year’s tradition, a character remembers having a different body when they were young – but their effect is undeniable. This is work that hums at the base of your skull, and it spreads through you like a deep and deliberate breath.

8. ‘Sunday’ by Olivier Schrauwen

We have all known wasted weekend days, with their mornings that slide into afternoons and evenings, leaving us with nothing accomplished and nothing gained. Schrauwen puckishly attempts to document such a lost day, capturing the second-by-second thoughts of his cousin Thibault as he drinks too much, avoids his neighbors, fantasizes about an old girlfriend, gets high and otherwise dissolves into the passing hours. Nervily illustrated and awash in a surreal color palette, “Sunday” may be the most original and exciting graphic novel of the last decade. And for all its formal experimentation, it is also a surprisingly winning, witty read – often funny and always fun.

9. ‘Vera Bushwack’ by Sig Burwash

With a chainsaw in hand and a dog named Pony at their side, Burwash’s protagonist, Drew, sets out to literally carve a space of their own out of the wilderness. Across kinetic fantasy sequences and quiet moments of conversation – all rendered in riotous, punky sheets of color – Burwash explores and pushes against the boundaries of gender while questioning what true independence entails. What emerges is something like a love story about learning to care for oneself.

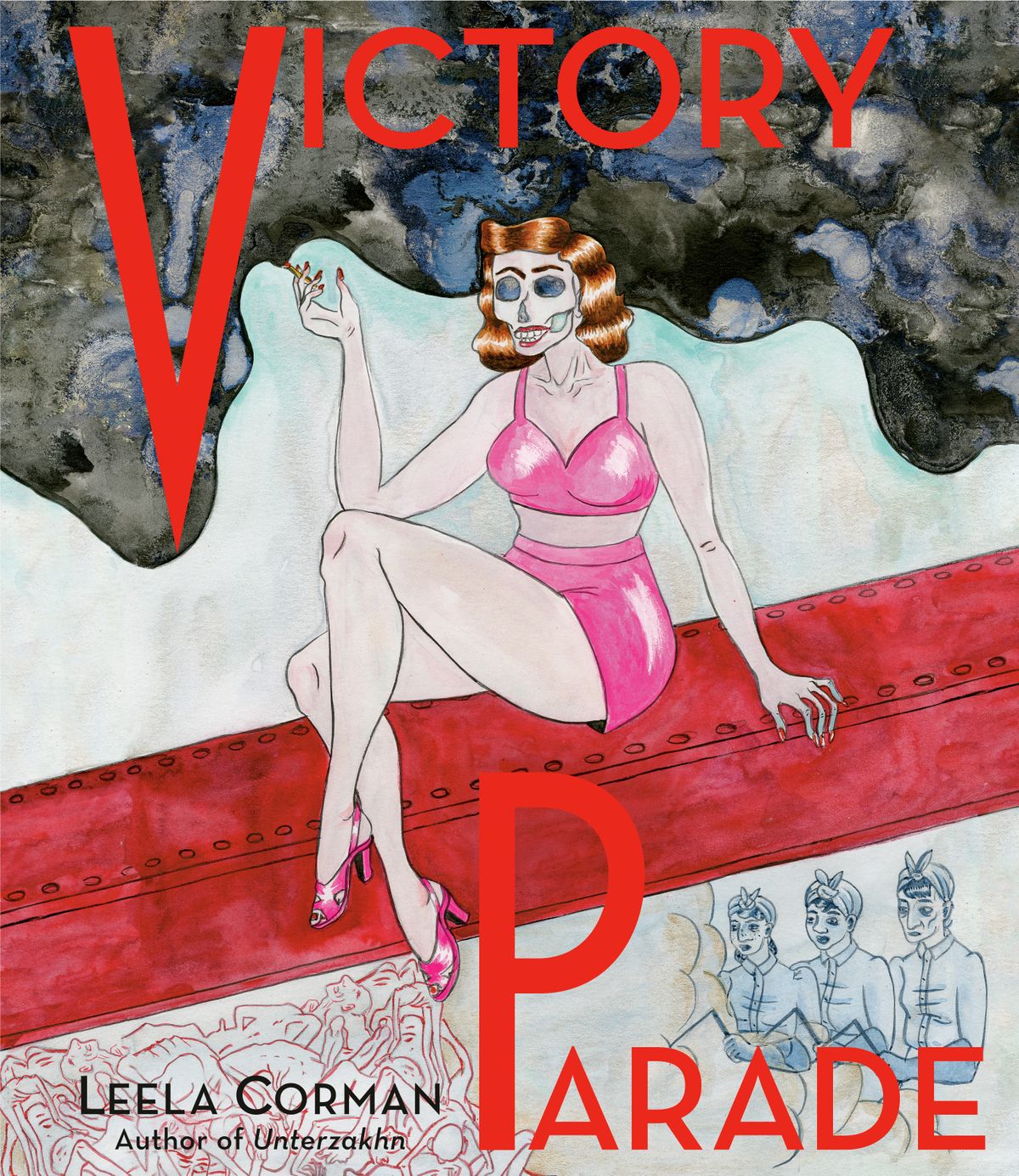

10. ‘Victory Parade’ by Leela Corman

Corman’s novel dips in and out of the lives of a group of women – Jewish refugees in particular – as they struggle to make lives and communities for themselves in the early 1940s. The book’s painterly style, which sometimes draws on German expressionism, ably captures the horrors of genocide, even as its narrative refuses easy answers. Haunting and haunted, “Victory Parade” depicts the reverberations of the Holocaust as they were felt in the moment, human in their dimensions precisely because they are so raw and rough in their expression.