‘My heart is happy’: Indigenous voices are a priority of new Columbia River Basin Treaty

Seeing salmon return to the Columbia River Basin has made Ktunaxa Nation member Troy Hunter’s “heart happy.”

The focus on returning the traditional food source to the water system is just one way the new Columbia River Treaty aims to respect Indigenous people in a way the United States and Canada have not done before, tribal representatives said at a symposium on the river Wednesday.

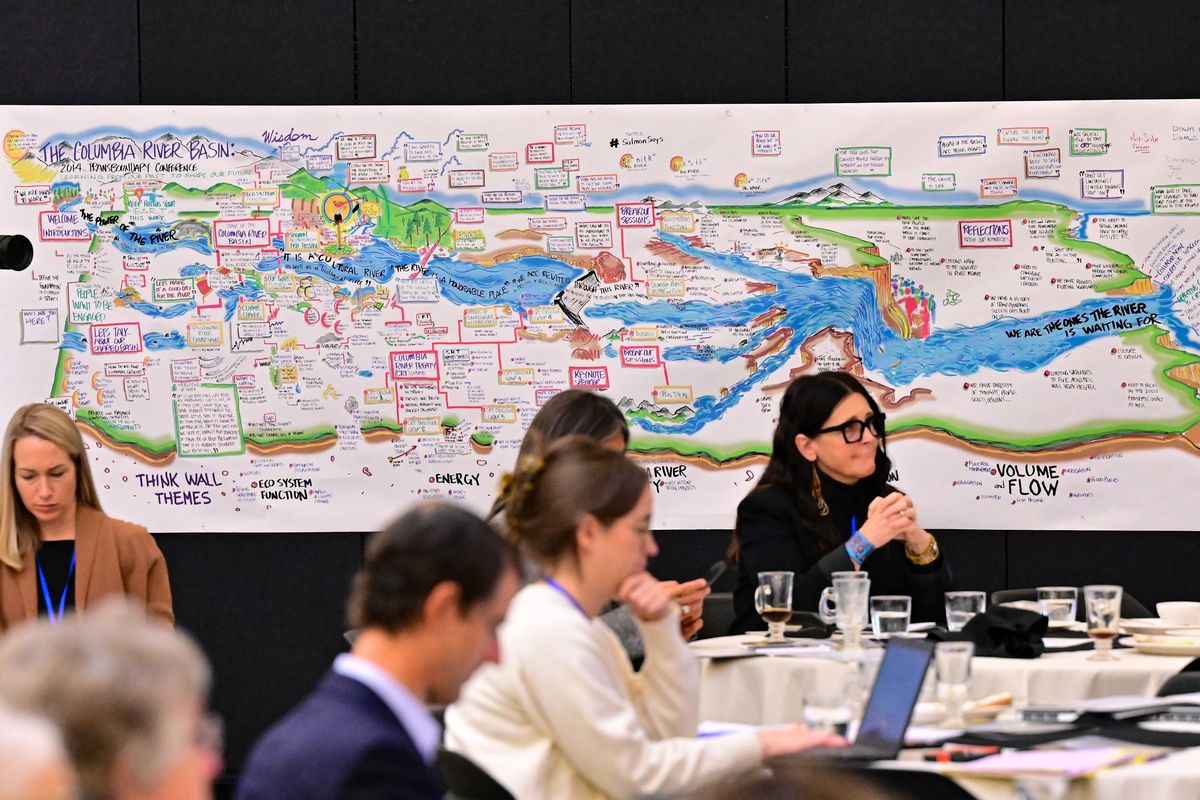

Hosted by Gonzaga University in Spokane, the symposium brought together negotiators who crafted the deal struck earlier this year. The United States and Canada announced in July they reached an agreement in principle to modernize the Columbia River Treaty, a 60-year-old pact that governs how the two nations use the Columbia Basin’s water resources.

In addition to those two nations, the negotiation process also included members of tribes and nations who have called the Columbia River Basin home.

When the Columbia River Treaty first was ratified in 1964, little attention was paid to how the agreement would impact the natural ecology of the river basin or the tribes that traditionally lived there.

Sixty years later, the new treaty included Indigenous voices in the negotiation and made ecological recovery a priority.

“We used to have a treaty that was focused almost exclusively on flood control and power generation,” said Jay Johnson, representative of the Syilx and Okanagan Nation during treaty negotiations. “That treaty reflected the era of the day in the ‘60s – building something to conquer nature and trying to make a better world that way. But that left out the ecosystems, left out the communities along the river, left out Indigenous voices.”

The United States and Canada began reviews of the Columbia River Treaty in 2013 and negotiation of a new treaty in 2018. The culmination of these efforts came in July this year when a new treaty was agreed to in principle.

When these negotiations began, the two countries shifted their approach to include more Indigenous voices.

“We started listening and having conversations with our First Nations,” Global Affairs Canada negotiator Stephen Gluck said. “I have to admit that was a change to how we traditionally do things.”

In the new treaty, the Joint Ecosystem and Indigenous and Tribal Cultural Values Body, known as the JEB, will include equal representation of Indigenous nations and tribes of the Columbia River, as well as the United States and Canadian governments. Recommendations of the JEB will be made by consensus of the tribes and the Indigenous nations.

If these directives are not followed in whole or in part, United States and Canadian governments are required to explain in writing why they will not implement the recommendations.

Ktunaxa Nation council member Maureen DeHaan said the JEB “finally” gives Indigenous communities a voice in the Columbia River Basin.

“Recommendations are expected to be implemented to the best of the agencies and parties’ abilities. And if they cannot implement them, they must provide rationale for why they are not able,” she said.

Salmon reintroduction

A focus of the treaty will be the reintroduction of salmon to the Columbia River and its tributaries. Upon completion of reintroduction studies, JEB is expected to provide recommendations on long-term reintroduction programs. At least every five years, it will review the results of reintroduction activities completed and make recommendations on reintroduction.

Troy Hunter said the possibility of salmon crossing all throughout the river basin “made his heart happy” – translating a traditional saying from his peoples’ language.

“Where our people gathered, salmon was always there. It was ubiquitous. It was something that we could rely on. It was our food, our staple,” he said. “That salmon was included in this negotiation is a major milestone for all of us. We are trying to fix something here.”

Flood control

Under the new agreement, the United States will continue to have access to Canadian dams’ storage space in the case of flooding, though the amount of storage will decrease. This will make the amount of water coming into the United States more predictable and facilitate easier shipping, agriculture and salmon reintroduction, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers treaty negotiator Pete Dickerson said.

Under the previous treaty, the United States had access to 8.95 million acre-feet of Canadian reservoir storage. Under the new agreement, that will decrease to 3.6 million acre-feet, for which the United States will pay Canada $37.6 million each year.

Dickerson called this a “slight reduction” from the storage the United States enjoys today.

State Department lead negotiator Jill Smail said the Canadian-based storage is used because it is “the most efficient and effective storage to reduce flood damage and flood risk in the United States.” If major flooding events do exceed the 3.6 million acre-feet, the United States can still call upon Canada for additional assistance, she added.

Hydropower

The Columbia River and its tributaries provide the United States with over 40% of its hydropower energy. That energy production is shared between the Bonneville Power Administration and Canadian government-owned utilities. In the new agreement, the United States will provide Canada with 37% less in hydropower than in the previous treaty – with an ultimate decrease of 50% by 2033.

BPA lawyer Hub Adams said this decrease “approximates the true value” of the power being provided to Canada. Having these rates built into the agreement will “avoid a lot of disruption and potentially protracted disagreements” over what the amounts could be.

“We had been looking at a lot of years of disagreements on plans for power operations and entitlement. That would have brought a lot of uncertainty, instability and disruption.”

The agreement will bring stability to both governments and reduce costs for ratepayers in the region and across the continent, he added.

Kathy Eichenberger, lead negotiator for British Columbia, said the new agreement would allow the Canadian province “more flexibility” on how it operates its reservoirs and obtains energy. While the initial funds Canada receives are lower, the new agreement allows for “certainty over the longer term.”

BPA and Canadian utilities are also considering expanding transmission on the east side of Columbia River Basin, Adams said.

A planned study will consider developing a new transmission line between BPA’s Bell substation near Spokane and the Canadian border.