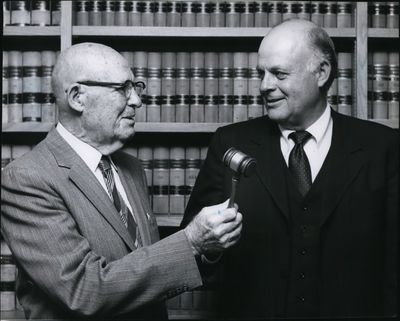

Longtime federal Judge Justin Quackenbush remembered as ‘true jurist’ with ‘a passion for the law’

A stickler for preparation, U.S. District Court Judge Justin L. Quackenbush could make attorneys’ lives uncomfortable if they made the mistake of appearing before him unprepared to argue either their case or the corresponding law.

Quackenbush, 95, died on Oct. 27. His memorial service was held Saturday at Saint Stephens Episcopal Church, at 5720 S. Perry St.

In his later years, Quackenbush presided over cases in the building that still bears the name of longtime friend and colleague, former U.S. Speaker of the House Thomas S. Foley. Quackenbush also presided over conflict cases in Southern California, Nevada and Arizona that happened to coincide with colder months in his hometown of Spokane.

Former U.S. Attorney Joe Harrington said walking into a court hearing before Quackenbush, which he did dozens of times over his career, could be intimidating.

“He expected all the parties to be extremely prepared,” Harrington said. “He would enjoy discussing legal issues and factual issues, and expected attorneys to respond appropriately. If you weren’t prepared, it could be very uncomfortable appearing before Judge Quackenbush.

“He was also wicked smart and a true jurist,” Harrington continued. “He had a passion for the law.”

Vanessa Waldref, the current U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Washington, issued a brief statement Monday offering her condolences to Quackenbush’s family.

“Judge Quackenbush was a dedicated member of the federal judiciary, who served with distinction for more than four decades,” she wrote. “His commitment to justice, fairness, and the rule of law left a lasting impact on the legal community and those who had the privilege of appearing before him.”

Born in October 1929, the same month of the “Great Crash” of Wall Street that plunged the country into the Great Depression, Quackenbush grew up in Spokane and followed his father into law.

His parents, Marian L. and Carl C. Quackenbush, both worked as teachers at Hillyard High School in Spokane. Carl Quackenbush later earned his law degree from Gonzaga University School of Law by attending night classes, according to the younger Quackenbush’s published obituary.

Justin Quackenbush grew up in the family home in the Audubon Park area of Spokane before graduating North Central High School. Upon graduation, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s officer training program and finished at the University of Idaho.

Upon graduation, Quackenbush served aboard the Navy destroyer USS Arnold J. Isbell, a Gearing-class destroyer during the Korean War.

While serving in the Navy, he married fellow Idaho alum Polly Packenham in 1952, and they would later have three children.

Two years later, after completing his military duties, Quackenbush followed his father and started studying law during night classes at Gonzaga. During the day, he worked as a court clerk for the late Spokane County Superior Court Judge Ralph E. Foley, who served from 1940 to 1974.

It’s through that job that Quackenbush met and became lifelong friends with Judge Foley’s son, Tom.

“Tom is the great resolver,” Quackenbush told The Spokesman-Review in 1989. “I think that’s a trait inherited from Judge Foley. He was the kind of person who really thought disputes should be resolved by mutual agreement.”

Foley “was renowned for attempting to get people to compromise and settle their differences even in the middle of trial,” Quackenbush continued.

“Those of us who practiced in front of Judge Foley would sometimes become a little impatient because we knew he was going to call us into his chambers and ask if we had pursued every avenue in an effort to resolve the matter without the necessity of having a winner and loser.”

After completing his law degree in 1957, Quackenbush became a deputy prosecutor for Spokane County. In 1960, he then went into private practice with friend Jack Dean. Together, they formed the firm of Quackenbush, Dean, Bailey and Henderson.

He worked as a private attorney until 1980, when then-President Jimmy Carter nominated Quackenbush for the lifetime appointment of federal judge. Some 15 years later, in 1995, Quackenbush entered senior status.

The judge was also a major Gonzaga basketball fan. In honor of his legacy, Gonzaga Law School once every two years hosts the Quackenbush Lecture, where the school brings in renowned jurists and academics to speak with students.

Harrington, the former U.S. attorney, explained that federal judges in senior status can hear as many or as few cases as they choose.

“There was also part of him that was fun loving,” Harrington said. Quackenbush “had great stories about the history of Spokane. I recall one story about the time Bobby Kennedy came to Spokane on the campaign trail.”

Before becoming federal judge, Quackenbush’s greatest contribution may have been to boost his friend, Foley. Quackenbush served from 1964 to 1978 as campaign chairman for Foley two years before Quackenbush was appointed federal judge.

While Harrington said Quackenbush was fair to both sides, he loathed prosecutors who would talk about the evidence of their cases before trial.

He famously kept a newspaper clipping on the wall in his chambers about a federal prosecutor in California who commented about the strength of his evidence before a second set of defendants could go to trial.

Despite earning convictions against the first group of defendants, Quackenbush dismissed the cases against the second group because he believed the pretrial publicity violated their right to a fair trial.

As a result, the Eastern District of Washington was one of the few offices in the country that would not issue news releases about cases before they reached trial, Harrington said.

The Quackenbush effect “was the reason that the U.S. Attorney’s Office was very reluctant to comment on indictments,” Harrington said. “That lasted decades.”

Waldref, the current federal prosecutor, has again begun issuing news releases on suspects who face criminal charges prior to trial.

Harrington, who retired in 2023, said he was not sure at what point Quackenbush stopped hearing cases.

One of the last high-profile criminal cases that the judge heard was the 2011 case against Kevin Harpham, who admitted leaving a bomb on the planned route of the Martin Luther King Day Unity March.

In court, Quackenbush grilled Harpham about his motivations.

“It’s beyond my comprehension that you would stand there and not accept responsibility for what you have done,” the judge told Harpham. Quackenbush then sentenced him to 32 years in federal prison, which was the maximum allowed under a September plea agreement between federal prosecutors and Harpham’s public defenders.

Quackenbush said at the time that he hoped Harpham, who had no previous criminal history, would use his term in prison to come to grips with his racist views.

“As citizens of this country … it’s not us versus them,” Quackenbush said. “It’s us, regardless of our color, regardless of our political views, religious beliefs or heritage.”