Washington governor sends back plan for huge Tri-Cities wind farm, asks to add more turbines

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee on Thursday sent a letter to a government energy council saying it cut too many turbines out of the proposed construction plan for one of the largest wind farms in the state.

Earlier this year, the state Energy and Facility Site Evaluation Council sent the governor’s office a recommendation to downsize the controversial Horse Heaven Wind Project near the Tri-Cities. Inslee had 60 days to approve or reject the project recommendation, or to suggest changes to the proposal. In its response, the governor’s office wrote that it wants the stretch of land that will be developed to achieve “full or near-full” energy generation capacity.

“I direct the Council to focus mitigation on specific and narrowly tailored approaches that do not reduce the generation capacity of the Project,” Inslee’s letter reads.

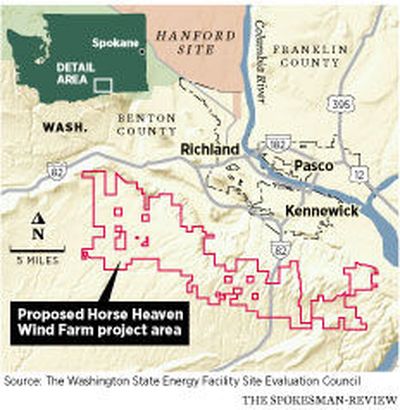

In 2021, Colorado-based company Scout Clean Energy asked the state for permission to build the sprawling wind and solar farm in Benton County, dotting a swath of land with hundreds of windmills and solar panels spanning more than 24 miles.

The proposal outlined the construction of at least 140 turbines stretching a minimum of 500 feet into the sky, plus arrays of solar panels and battery chargers.

The request spurred dispute among business owners, residents and environmentalists with vested interests in the wine country region situated between the Yakima Valley and the Columbia River in southeast Washington. The Tri-Cities is among the fastest-growing parts of Washington. Between 2010 and 2020, the region saw the most population growth per capita out of all of Washington, according to U.S. Census data.

Washington’s energy council met numerous times over the course of three years and came back with a counterproposal earlier this year to nearly halve the number of turbines built in the Horse Heaven project.

Among the groups that opposed the wind farm were The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. A testimony letter sent to the state last year explained the project would damage the cultural and historical significance of the Horse Heaven Hills.

Millennia before white colonial settlers took over the West, thousands of Native families, tribes and sub-bands inhabited the Horse Heaven Hills region, wrote Johnny Jerry Meninick, deputy director of culture for the Yakama Nation.

“When the United States came, they came with the purpose of eliminating us with armies,” Meninick wrote. “They also separated us and took our elders to stockades and children to boarding schools. They kept able men to help build new roads, harvest timber. … In many different ways, that same principle applies here.”

Meninick said the Yakama Nation reserved the right to maintain resources around Horse Hills.

In regard to opposition from the Yakama Nation, Inslee wrote in his letter that the energy council should “explore” requiring Scout Clean Energy to seek agreements for the tribes to access “highest priority, physical traditional cultural resources within the leased property boundary, including previously inaccessible sites due to it being private property.”

A small community group called Tri-Cities C.A.R.E.S. (Community Action for Responsible Environmental Stewardship) argues the project will drive down property values in the area and pose obstructions to emergency planes or hospitals in the event of a wildfire on the hills.

Paul Krupin said he and his fellow C.A.R.E.S. board members recognize the importance of renewable energy in the wake of climate change.

“This is just a really poor solution,” Krupin told The Spokesman-Review earlier this year. “This project? First, it doesn’t do anything to climate change at all. And second, it doesn’t produce power when we need it.”

Concerns by ecologists over risks posed by populations of ferruginous hawks were another reason the energy council cut the original plan to build more than 100 windmills down to 62, said Dave Kobus, senior project manager with Scout Clean Energy.

“We’ve got to find flexibility, so turbines are not isolated because of a twig on the ground (that means) a nest is no longer viable,” Kobus said. “We cannot build a turbine within 2 miles of twigs on the ground that happened to be a nest two years ago.”

In his letter, Inslee wrote that impacts to wildlife such as ferruginous hawks can be “adequately mitigated” without the council decreasing the proposed number of windmills, adding that other man-made variables have hurt wildlife in the region.

“The sad reality is that the ferruginous hawk population has declined to minimal levels at the site over many years, due to various factors including agricultural and residential land use decisions that pre-date this project,” the letter reads. “In fact, the record reflects that not a single ferruginous hawk has been seen nesting in the project area in the last five years.”

In the conclusion of his letter, the governor asked the energy council to draft another proposal for the project that allows greater energy generation and send it back to his desk for review.

Inslee directed the council to respond within 90 days to his request for a new draft. Then the governor must choose whether to approve or reject the wind and solar farm project.