Former Defense Secretary Mattis: Democracy is hard for a reason

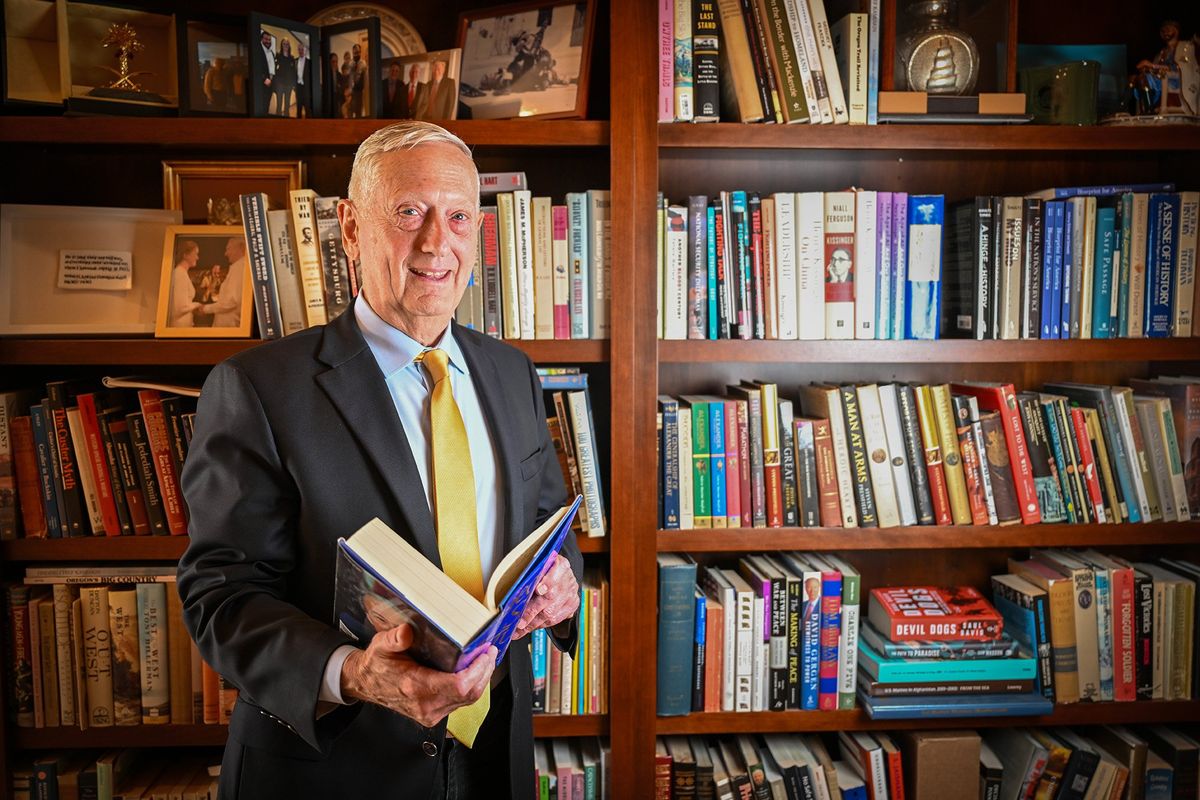

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense and four-star Marine Corps Gen. James Mattis will be the inaugural recipient of the Thomas S. Foley Award for Distinguished Public Service. Mattis will be honored by Washington State University’s Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service on April 9 during a ceremony at the John Hemmingson Center at Gonzaga University.

Leading up to that event, The Spokesman-Review sat down with Mattis for an in-depth conversation in which the Pullman native discussed a wide range of topics from current world conflicts and the expansion of NATO to the importance of the bipartisanship style of leadership that outlined Foley’s political career.

Over the next three weeks, The Spokesman-Review will publish excerpts from that interview. The transcript below has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

With a military career spanning decades – and not only seeing some of the key moments in our nation’s modern history, but being a central figure in many of those – what are the lessons and observations? And with that front-row view of history, what is the state of America’s democracy?

Looking back over 40-odd years of government service, the lesson that rings most true to me in all venues I have been in is that trust is the coin of the realm. If you have trust in the room, you can accomplish miracles. If there isn’t trust in the room, you are going to have challenges basically accomplishing anything.

So how do you build trust? How do you create ground for building trust, because sometimes you have to start from pretty far apart. That is where I put a lot of my effort based on the lessons I have learned over the years.

The lesson of my life would be that if you don’t build trust, then you are going to short-circuit yourself. You’re never going to achieve your potential, and you are going to be stalled out because if people don’t trust you, they’re not gonna be with you. And if they’re not with you, you are going to pay the price.

When you want to build trust, it is obvious that you are willing to accommodate, that you are listening with a willingness to be persuaded by someone else; you’re not just listening to them say, “Thank you very much,” and then you go right off and say, “I’m going do what I was going do in the first place.”

This is a primary lesson I have learned over the years.

I have seen great people come in all different shapes and colors, genders, whatever.

The one characteristic I have seen in all of the people I consider great is their ability to build trust – but it also is their ability to listen very, very keenly to what others are saying. I remember reading a biography about George Washington, and one of his aides said that Gen. Washington listened so well that he could even hear what was not being said. We know immediately what that means.

The ability to listen with the willingness to be persuaded and to build trust with the people you’re engaged with is critical to achieving greatness, because great things are done by teams, not done by individuals. If they could be done by individuals, then a general wouldn’t have an army, he would just go win the war on his own. If a city mayor can do the job on his own, why does he need the people? He would just go do all his work without anyone else’s help. It is about team building, it is about trust building and it is about the ability to listen to others with a degree of respect and curiosity that says maybe they have a good idea, even someone you disagree with. We have to remember that twice a day, a broken clock is right.

When we talk about Speaker Foley and his type of leadership, Speaker Foley could find ways to work with people across the aisle. We now call it bipartisanship, and he accepted that as key to democracy. One person doesn’t always get everything they want. That is not a democracy. There has to be compromise.

Today, some people look at compromise as a dirty word. It is important that we do not compromise on principle, but not everything people disagree with nowadays is principle. A lot of it is just opinion, and we are not our opinions. We can change our opinions, if there is data to support it.

I was brought up by the greatest generation. It was a sense amongst that generation that the country didn’t have to be perfect to be worth fighting for, to put it in the words of a World War II Marine. After all, we set up this experiment that we call America – and that is all it is, an experiment – to see if we could create a more perfect union, which assumes we were not perfect. It assumed we were going to have to travel the distance.

And guess what? In a government of the people, by the people, for the people, you are always going to be improving, and it is always going to be very hard work.

After that nasty argument with King George III, we knew we didn’t want a king. Our Founding Fathers actually intentionally set up a government that is very hard to make work. It was designed to be hard. It was designed to have three different power bases – the legislative, the judicial and the executive branches. It was designed so they would have to compete to make decisions. And guess what, just to make it really tough, the Founding Fathers also said, “Let’s add a Senate,” so that now a bicameral legislature would both have to agree for something to become a law. They set it up to be hard. But it also is noble and important work.

Especially for the young people in our nation, they need to understand that this country is still being built. It is not finished, and every generation needs to build on it.

I think that has been lost some, because – as a nation – we have been around for a long time. We know our streets are paved and the street lights come on automatically every night. We know there is a policeman there if we need him. And, of course, we know we have the freedom of speech, because we have always had that in our country. But in the history of the world, there are not many people who have enjoyed the freedoms we have, and we owe it to the next generation to carry that responsibility forward. I don’t know that we feel the same level of responsibility that the greatest generation did. They came through a global depression, a horrible world war, and they still thought we could always be better as a nation.

The Civil Rights Act comes out of that belief. We see all sorts of other progresses enacted to help us improve as a nation. We are a better nation today than we have ever been, and we are going to be even better tomorrow.

Democracy is still alive and well.

The argument after the last election was whether or not it was honest, and that has been settled very forthrightly in every court case where they heard all competing versions, and the truth won out. Unfortunately, I think we have taken an injurious view of people who disagree with us in many cases. We can’t keep using this scorching rhetoric and say that we are going to have a compromise on most issues if we keep doing this gladiatorial combat and saying that takes the place of political discourse. We need political discourse with good, strong arguments that lead to an agreement on a compromise that says, “And here’s how we’re going to address it.” But if we don’t get to that point, then eventually this experiment is going to fail, because it was set up by the Founding Fathers to require us to compromise. It was purposely set up to require that.

We have to get back to teaching that in our schools.

And for adults, especially those with my color of hair who are setting such a poor example of leadership – I wouldn’t even call it leadership, because it is too infantile – they are going to have to start carrying the responsibility of taking care of this country and handing it over in as good a shape or better than they got it. Right now, I don’t think the people with my color hair are doing that.