Cool Critters: Bobcats are common in our region, but typically only their pawprints are visible

A male bobcat north of Yakima that was GPS-collared last winter as part of a WDFW study. Between their camouflaged appearance, ghostlike traits and wariness of humans, bobcats are rarely seen. (Courtesy of Lindsay Welfelt, a WDFW wildlife biologist)

Bobcats are everywhere and nowhere. They saunter across backyards, cul-de-sacs and golf courses and sit atop fences. Even in the Spokane area. And yet, we rarely see them.

How can that be?

Bobcats are the most widespread wild cat in North America and live in a variety of habitats, including forests, grasslands, deserts and marshlands. And now, suburbia.

As human development alters wildlife habitats, these secretive animals are learning to adapt to their Homo sapien neighbors. So unless you live in the busier parts of Spokane or the Tri-Cities, there’s a good chance a bobcat roams nearby.

“Found throughout all of Washington, bobcats are probably more common than most people realize,” the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife says on its website. “They appear to be using suburban settings more often, although due to their reclusive ways, they are not often seen.”

With more wildlife cameras being installed by property owners, researchers and nature organizations, bobcat sightings have increased in recent years, most during nighttime prowls, according to the WDFW. Oblivious to wildlife cameras, the cats work the night shift to avoid being seen in urban areas, quietly hunting for mice, rats, rabbits, birds and other small animals.

A growing body of research supports the premise that not only do bobcats increasingly cross the road, but they do it at night. A 2003 study published in the journal, Conservation Biology, found that urban sprawl west of Los Angeles had turned the large felines into night owls. The bobcats established there were much more active at night than their peers in the wild, researchers concluded.

In a 2018 study published in the journal, Science, scientists concluded that a “fear of humans” is driving bobcats and other animal species to adapt to more nocturnal schedules.

Whether ambling about in human-altered settings or in their natural habitat, bobcats’ ghostlike ways make them challenging to study, said WDFW wildlife biologist, Lindsay Welfelt.

“They’re quiet, clever and solitary, which makes it hard to track them,” said Welfelt, who’s finishing her first year of field research in Kittitas County, north of Yakima.

In landscape covered in brush and trees, Welfelt uses cage traps baited with wild meat to lure the bobcats. Once captured, they glare with large yellow eyes, “hiss, growl and retreat to the very back of the cage,” she explained. “What some people might perceive as aggressiveness is typically fear.”

Another reason bobcats are so seldom seen is their camouflaging. Their buff to brown “earth tone”-colored fur is mottled with dark streaks and spots, allowing them to blend into backdrops that include brush, rocks and soybean fields as well as roadways and buildings.

Once, after releasing a captured, GPS-collared bobcat to its habitat north of Yakima, Welfelt watched as it scurried up a nearby hill.

“At first I thought the bobcat had cleared the hill and disappeared, only to realize that it was still within eyesight,” she recalled. “It blended in so well and was so agile in its movements that I could barely see it.”

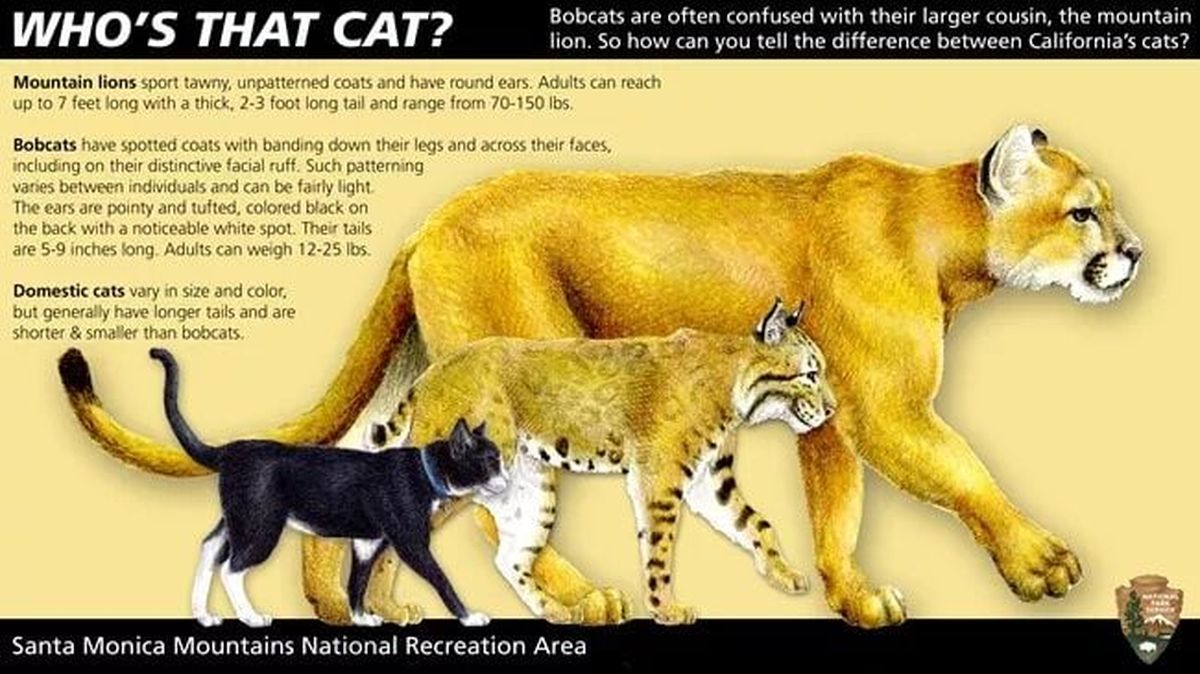

If you think you see a bobcat, either in person or by remote camera, here’s what to look for: Bobcats are about twice as large as a domestic cat, but more muscular and with larger, more stocky legs. They’re named after their short, 5- to 7 -inch “bobbed” tail, with an end that looks dipped in black ink. Their tannish fur sometimes has a reddish tint and is patterned with darkish spots and stripes. Small black tufts protrude from each pointy ear, and ruffly fur extends outward from their cheeks.

Bobcats are unlikely to attack humans, choosing to dart off when approached, Welfelt explained. However, like any wild animal, they may fight back if threatened, or if they are sick or injured.

Which means, should you ever encounter one, watch it from the distance and feel fortunate. After all, skilled field researchers can go days and nights without spotting a single bobcat in the flesh.

But as Welfelt points out, “that doesn’t mean they’re not out there, watching us.”