Supreme Court curbs federal agency power, overturning Chevron precedent

The Supreme Court on Friday sharply curtailed the power of federal agencies to regulate vast parts of American life, sweeping aside a 40-year-old legal precedent that the government relied on to defend thousands of rules on everything from the environment to banking to drugs.

The 6-3 opinion along ideological lines was a victory for conservatives, who have long said federal agencies wield too much power to impose regulations that burden business and stifle innovation. Legal experts said the decision will lead to a flood of challenges to regulations.

For decades, the court’s decision in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council directed judges to defer to the reasonable interpretations of federal agency officials in cases that involve how to administer ambiguous federal laws.

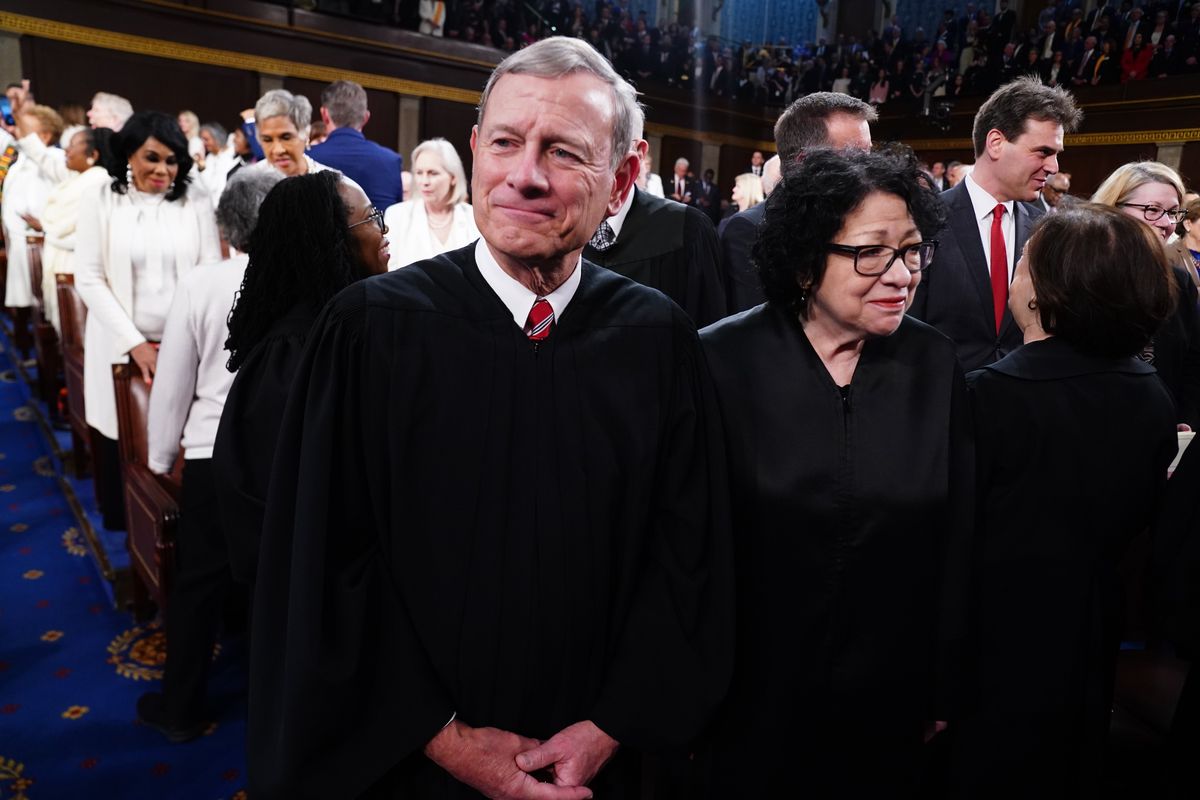

But writing for the majority, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said the Chevron framework has proved “unworkable” and allowed federal agencies to change course even without direction from Congress.

“Chevron was a judicial invention that required judges to disregard their statutory duties,” Roberts wrote.

He added the ruling would not call into question previous cases that relied on Chevron but gives judges the power going forward to determine if agency actions are reasonable.

The court’s three liberal justices – Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson – dissented, with Kagan writing that the majority has turned itself into “the country’s administrative czar.”

In a lengthy dissent read from the bench, Kagan said the court discarded precedent, unwisely setting up the Supreme Court – and courts in general – as the final arbiter on regulatory matters in which they are not experts. Kagan said that power rightly belongs with federal agencies.

“In every sphere of current or future federal regulation, expect courts from now on to play a commanding role,” Kagan wrote in her opinion. “It is not a role Congress has given them. … It is a role this court has now claimed for itself, as well as other judges.”

Kagan said Friday’s ruling would cause “breathtaking change” and shift power to the courts.

The long-standing precedent, she wrote, “falls victim to a bald assertion of judicial authority. The majority disdains restraint, and grasps for power.”

The precedent, established in 1984, gave federal agencies flexibility to determine how to implement legislation passed by Congress. The framework has been used extensively by the U.S. government to defend regulations designed to protect the environment, financial markets, consumers and the workplace. Friday’s decision represented the third time in as many years that the court has jettisoned major legal bedrock, after overturning Roe v. Wade and undoing affirmative action in college admissions.

While lower courts have relied on Chevron in tens of thousands of cases evaluating federal rules and orders, conservatives have balked at the legal precedent – and the approach has fallen out of favor in the last decade as the Supreme Court moved to the right. The high court’s conservative supermajority includes three justices nominated by former president Donald Trump, whose administration put a premium on judges skeptical of federal government power and the “administrative state.”

Friday’s ruling is the court’s most significant to date in decisions paring back the power of the executive branch. In a separate ruling Thursday, the court limited the Securities and Exchange Commission’s reliance on in-house tribunals used to resolve securities fraud cases, a decision that could also affect two dozen other agencies with similar bodies. Also this term, the high court struck down a Trump-era ban on bump stock devices that allow rifles to fire hundreds of rounds a minute.

Supporters of Chevron – including environmental groups, labor and civil rights organizations and the Biden administration – told the court that Congress often writes broad statutes to give government experts the leeway to address emerging complex problems.

Sambhav Sankar, a vice president at Earthjustice, said in a statement that the court’s decision “threatens the legitimacy of hundreds of regulations that keep us safe, protect our homes and environment, and create a level playing field for businesses to compete on.”

The court’s conservative majority is “aggressively reshaping the foundations of our government so that the President and Congress have less power to protect the public, and corporations have more power to challenge regulations in search of profits,” said Sankar, who was a law clerk to the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Opponents of Chevron said the framework unfairly tips the scales in litigation by requiring judges to systematically favor government regulators over those challenging burdensome regulations. Chevron has allowed federal agencies to flip-flop and impose different rules each time a new administration takes over, they said, leaving judges with little choice but to defer to the changing interpretations of agency officials.

“Today’s decision vindicates the rule of law,” Roman Martinez, an attorney for the plaintiffs in one of the cases decided Friday, said in a statement. “By ending Chevron deference, the court has taken a major step to shut down unlawful power grabs by federal agencies and to preserve the separation of powers.”

Allison Larsen, who teaches administrative law at William & Mary Law School, said the court’s decision to toss Chevron will lead to less predictability and a lack of uniformity as lower courts around the country assess agency decisions in different ways. That’s because judges, instead of agency experts, will now get to make scientific and technical judgments about how to interpret ambiguities in statutes, she said.

While the court could have limited Chevron’s reach, “six justices decided that wasn’t enough. That’s a bold move,” Larsen said.

Health law and policy experts have long warned that the demise of Chevron would also complicate the work of the Food and Drug Administration, which is tasked with regulating the safety of thousands of products that wind up in refrigerators, cupboards, veterinarian offices, medicine cabinets, hospitals and even playgrounds. The decision is expected to lead to a flood of lawsuits challenging FDA decisions and could also inject uncertainty in the process of drug approvals.

“Industry likes predictability,” said Holly Fernandez Lynch, an assistant professor of medical ethics and law at the University of Pennsylvania. “Predictability is good for investment and innovation.”

Even without the Chevron doctrine, the FDA’s authority and expertise should allow the agency to do its job effectively, said Peter Pitts, a former FDA associate commissioner and president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, a research organization that receives funding from pharmaceutical companies.

“The administrative state isn’t dead – it’s just going to have to work harder,” Pitts said.

The ruling could also lead to different regulatory schemes in different parts of the country.

Kevin King, an appellate lawyer and former law clerk to the late Justice Antonin Scalia, said with courts no longer required to defer to agencies, “it is more likely that courts will reach differing and sometimes incompatible conclusions about what federal statutes mean – leaving businesses exposed to a patchwork of interpretations that may be difficult to manage at times.”

King predicted the ruling would lead to “geographic uncertainty” with liberal-leaning courts in California reading statutes differently, for instance, than conservative leaning courts in Texas.

In response to concerns about a lack of uniformity, Roberts said judges had long applied Chevron inconsistently. “There is little value in imposing a uniform interpretation of a statute if that interpretation is wrong. We see no reason to presume that Congress prefers uniformity for uniformity’s sake over the correct interpretation of the laws it enacts.”

Roberts said the flaws in the framework were “apparent from the start, prompting this Court to revise its foundations and continually limit its application. It has launched and sustained a cottage industry of scholars attempting to decipher its basis and meaning. And Members of this Court have long questioned its premises,” he wrote, adding that “for its entire existence, Chevron has been a “rule in search of a justification,” if it was ever coherent enough to be called a rule at all.”

The pair of cases before the court, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce, were brought by Atlantic herring fishermen in New Jersey and Rhode Island who challenged federal rules initiated by the Trump administration requiring them to pay for at-sea monitors.

Both lawsuits were backed by conservative legal organizations – the Cause of Action Institute and New Civil Liberties Alliance – that have received millions of dollars from the Koch network, founded by billionaire industrialist Charles Koch and his late brother, David Koch.

The opinions issued Friday, laid out in more than 100 pages, illustrate the deep divide between how the conservative majority and the court’s three liberal justices view the role of federal agencies.

Roberts said Chevron was misguided from the start, in part because “agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do.”

Even when a case involves a highly technical matter, he wrote, “it does not follow that Congress has taken the power to authoritatively interpret the statute from the courts and given it to the agency. Congress expects courts to handle technical statutory questions.”

In contrast, Kagan wrote that Congress intended for agency experts to determine the meaning of unclear regulations involving technical subjects such as squirrel populations, Medicare reimbursements and what qualifies as a protein regulated by FDA.

“Agencies often know things about a statute’s subject matter that courts could not hope to,” she wrote. “Agencies are staffed with ‘experts in the field’ who can bring their training and knowledge to bear on open statutory questions.”

Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) said the demise of Chevron would create “a regulatory black hole that destroys fundamental protections for every American in this country.” He promised to introduce legislation to protect the government’s policymaking ability.

- – -

David Ovalle contributed to this report.