Native American citizenship, a century later: Looking back on the national Indian congresses that followed in Spokane

A century ago this month, Congress made all Native Americans citizens of the United States. In Spokane, this was a rallying cry for the first National Indian Congress, a gathering held over the next two years that grew solidarity and collaboration between tribes.

Before the Indian Citizenship Act, the Fourteenth Amendment had been interpreted to not include Native people, who were considered members of separate nations.

Native Americans could become citizens through naturalization, but they usually had to renounce their tribal affiliation. The new law signed by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924, made U.S. citizenship automatic and compatible with tribal membership.

However, citizenship didn’t automatically grant all civil rights. Some states, for example, didn’t recognize the right to vote until several decades later.

“Basically, the message was now you are no longer third-class citizens,” said Warren Seyler, historian of the Spokane Tribe. “Citizenship was just one of the steps that got us closer to getting accepted.”

In the aftermath of World War I, advocates argued for citizenship based on the disproportionate number of Native Americans who volunteered to fight in Europe.

Mel Tonasket, a Colville Tribes historian and longtime member of the Colville Business Council, said those who served didn’t want the war to spread to this continent.

His grandfather, born in 1896, was among those to serve in the Great War.

“He wasn’t looking at it as defending the United States, but his homeland,” Tonasket said. “He was willing to fight for this land and our way of life.”

In his grandfather’s opinion, the citizenship act was passed so that Native Americans could be drafted to the military.

At the time, the act wasn’t treated as major news, and the papers largely skimmed it over. The Spokane Daily Chronicle ran a two-paragraph brief a few days later with the headline, “Give All Indians Citizen’s Rights Through New Act.”

The full article read: “WASHINGTON, June 5 – The new Indian citizenship act recently signed by President Coolidge will make every native born Indian in the country a citizen of the United State, Indian Commissioner Burke said today.

“The granting of citizenship, however, he said, would not remove the restrictions on Indian lands under government guardianship, the supreme court having held that wardship is not inconsistent with citizenship. Indians’ rights to tribal or other properties are not affected.”

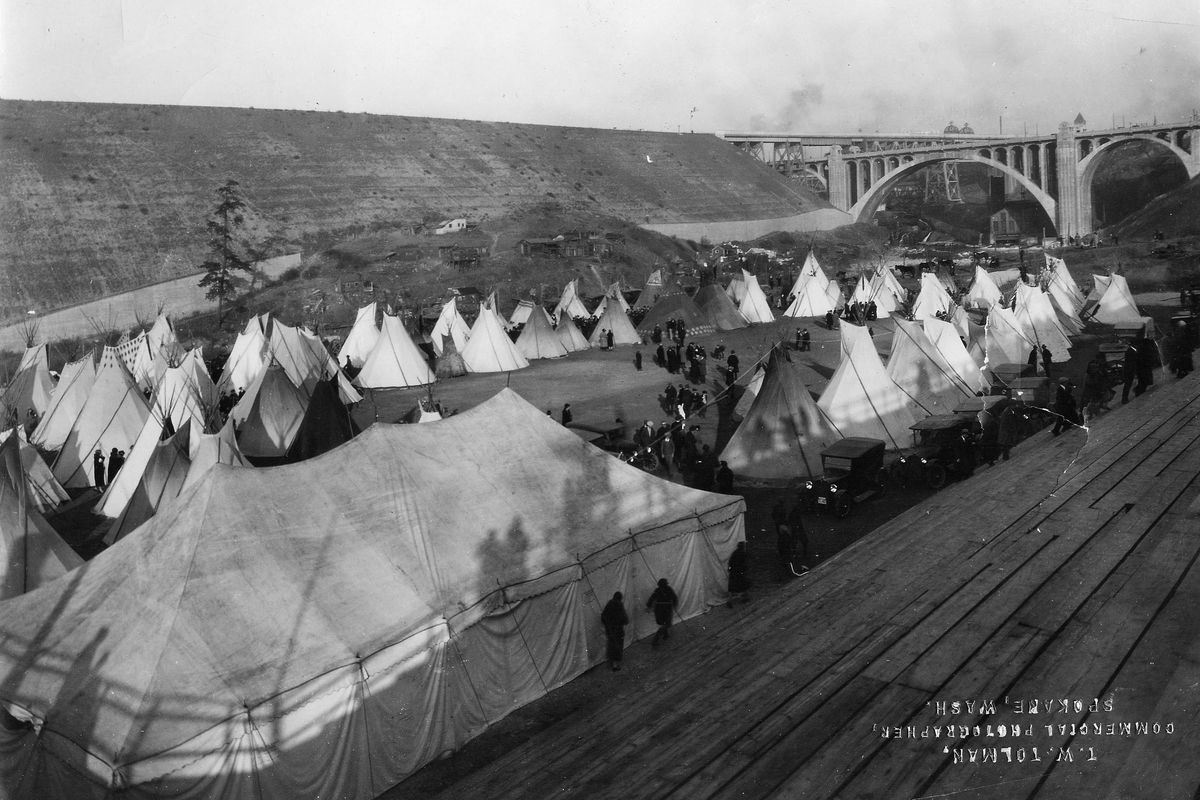

Even so, it was an inspiration for the first National Indian Congress held in Spokane a little over a year later in October 1925 and another in July 1926. The events drew thousands of participants from more than 30 tribes predominantly from the Northwest and Canada, but included tribes as far as Iowa.

The congress was planned by the Spokane Betterment organization and five northwest state governors, largely as a tourist ploy focused on the stereotype of the vanishing Indian – the myth that Native Americans and their culture were going extinct.

Photos from the congresses show fantastic displays of tepees pitched downtown and parades of attendees wearing traditional regalia.

But tribes and activists took advantage of the momentum behind the event. Between festivities, they also held serious talks and conferences on topics like education and land rights, said Anna Harbine, archivist for the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture.

Harbine curated the exhibit “1924: Sovereignty, Leadership, and the Indian Citizenship Act.” Using a timeline with quotes, archival photos and film footage, the exhibit focuses on the people and leaders rather than the spectacle.

“The Native communities had their agenda, and the Spokane community had their own agenda,” said Tisa Matheson, a member of the Nez Perce Tribe and curator of the museum’s American Indian Collection. “Whatever the event evolved into, there was stuff that got accomplished and there was stuff that wasn’t. But it was still a start of something.”

The congress was a precursor that led to more formal intertribal groups a few decades later, such as National Congress of American Indians and the Affiliated Tribes of the Northwest.

Discussions asked what it meant to be a citizen and what it meant to vote. There was a lot of confusion about what, exactly, citizenship meant, Harbine said.

“It didn’t just mean that suddenly they were full autonomous citizens and had every right that every other person in the United States did,” she said. They still had many restrictions governed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Harbine hopes the exhibit encourages visitors to consider some of the same questions.

“The goal was to get people to just think about that idea of what it means to be Native American, a member of a tribal nation, as well as being a U.S. citizen and that duality,” she said.

Before the citizenship act, these kinds of conversations weren’t happening on reservations.

“We were just trying to survive,” Seyler said.

At that time, tribes were still organized under a chief system and didn’t have modern tribal governments. Essentially everything was dictated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. So, for many who attended, it was their first time to leave the reservation.

“What the act did was it gave us that mindset to think differently, that we will no longer be controlled absolutely by the BIA,” Seyler said. Still, it would take decades through the self-determination movement in the ’70s and ’90s before tribal governments retained local control, he said.

A long history of treaty violations and official acts that diminished tribal sovereignty before and after 1924 is the reason Tonasket got involved in tribal politics. Looking back, he takes a more pessimistic view than Seyler.

“Was the act good for us? In my opinion, no,” Tonasket said. “The act itself helped the United States more than it helped the tribes.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the tribal affiliation of Tisa Matheson.