How fentanyl’s despair ravages the streets of Spokane: ‘This doesn’t mean I want to die’

A man takes a hit of fentanyl after heating a ground-up pill on foil on March 20 in the area of 2nd Avenue and Division Street. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

A passerby thought the man under the white sheet could be dead.

But when two members of the Spokane Fire Department’s Behavioral Response Unit pulled back the covering, he awoke and pointed to the needle scars on his arm.

“This doesn’t mean I want to die,” he said on a cold day in February. “This means, ‘Help me.’ ”

Paramedic Jordan Johnson retrieved a dry blanket for the man, identified only as “Adam,” who was soaking wet from hours of laying outside Browne Elementary School in the rain. As Adam wrapped himself in the blanket, he fiddled with his pill bottle sitting on the concrete that was only labeled with his first name.

Johnson snatched his portable monitor from his truck and began checking Adam’s vitals. He would live another day.

Jordan Ellinwood, a Frontier Behavioral Health clinical mental health counselor, had seen Adam before : A year ago, he went to a detox center but assaulted a staff member and declined to take part in a 28-day program to get clean.

As the two spoke to him with empathy, Adam expressed interest in trying again and opened up about his life.

“I’ve lived in the darkness in Spokane,” Adam said. “Sometimes I couldn’t wait to die. I was introduced to fentanyl in 2021 … When something happens, I just go get a bag.”

Fentanyl has left hundreds dead in Spokane. Hundreds more have overdosed and survived.

Residents may notice a person sitting on a curb, leaning against a building or crouched in a car seat with a blanket or a hood pulled over their heads. There’s a likelihood they are smoking fentanyl from foil wrappers that will end up as litter on the street.

The problem spurred the mayor of Spokane to declare a public emergency with the promise of more responders, more treatment and even more police sweeps.

For Adam, drug use is a family affair. His brother introduced him to fentanyl because it was cheaper than heroin. Drugs killed his father.

Adam has been “Narcanned” – or treated with the reversal drug naloxone – nine times in his life. He acknowledged he never learns.

“I once (stole) from a grocery store to buy drugs. But that isn’t who I am,” Adam told Ellinwood and Johnson. “I don’t want to hurt people. But when I’m on drugs and then I come down, it feels that way.”

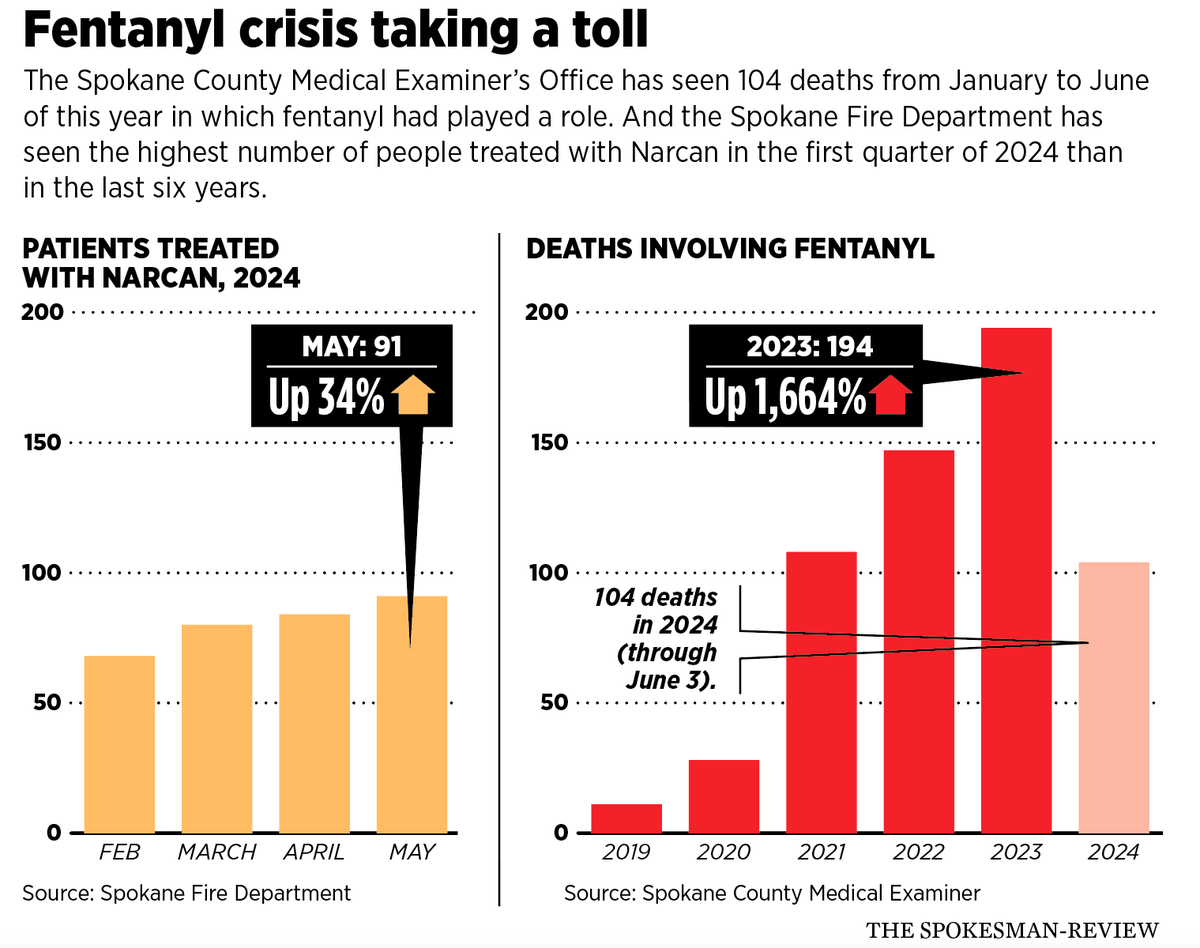

The Spokane County Medical Examiner’s Office reported 104 people have died from using fentanyl in the first five months of this year. The Spokane Fire Department reported the number of people treated with naloxone from January through March was higher than at any time in the past six years.

The day Johnson and Ellinwood responded to Adam asleep on the sidewalk, they were two days into a new program with the fire department’s Behavioral Response Unit. They have seen a rise in drug-related calls, mostly in densely populated areas and lower-income neighborhoods.

The new program aims to link people with shelter, support and treatment after an overdose. It began in early February as the only co-responding behavioral team within the fire department able to administer buprenorphine.

A typical response to someone in overdose would include the administration of naloxone to reverse it, but the drug puts the person into immediate withdrawal after it’s administered, Ellinwood said. This can cause an overdosing person to startle awake – sometimes becoming aggressive – until they walk away to find drugs to relieve the withdrawal symptoms. Unlike naloxone, buprenorphine will pause withdrawal symptoms for 24 hours, said fire department spokesperson Justin de Ruyter.

It can be enough working time to get someone into substance treatment. But there’s a catch.

The person who overdosed has to meet certain opiate withdrawal criteria based on their current symptoms, be stable enough to consent to the drug and agree to begin some form of substance treatment – something not everyone wants to do. And since the first day of the behavioral unit’s program in February, they’ve only administered buprenorphine, also called by its commercial name Suboxone, twice.

That’s 0.6% of people who were treated with naloxone in Spokane since February.

“If you wake someone up with Narcan, they might not always be happy,” Johnson said, adding that often the person would rather be left alone than prodded by paramedics.

Though Adam wasn’t overdosing this time, the behavioral team arranged for transportation to take him to a shelter where he was expected to receive follow-up by Spokane CARES, a social work program embedded within the fire department to connect people to resources like substance use treatment, mental health care and housing.

As Johnson leaned against the fire department’s SUV, he watched a cab take Adam to a shelter.

“I’ve never heard anyone tell me their story like that,” he said.

‘I don’t know what it’s like to live’: Spokane’s downtown

As he sat across the street from the Donna Hanson Haven housing complex on a warm day in May, a man identified as Jordan, who didn’t share his last name, pulled out a small jar of fentanyl powder and brushed his finger over the rim of the open lid.

“This is what it looks like,” Jordan said. “It’s not fun anymore.”

When Jordan was 13, his older cousin introduced him to crack cocaine.

Known on the street as “J3,” Jordan frequents the area of Division Street and West Pacific Avenue on the weekends. Unlike some of his friends using drugs downtown, he said he works a steady job.

Jordan’s friend Trey, who also declined to share his last name, pulled out a foil and began smoking a pill as they sat on the concrete. Fentanyl delivers a high that lasts about 20 minutes, Jordan said. So, as people tend to use more to create a longer high, they steadily build tolerance. But Jordan said he has seen 10 people overdose in one day and been given naloxone – sometimes by emergency responders, sometimes by fellow users.

He said he had a good family while growing up in Moses Lake. They went to Disneyland multiple times, which is to him a sign of a privileged, loving family – and never experienced or witnessed extreme trauma.

But that one hit of crack at age 13 made him feel like he wanted to kill someone. Since then, he has tried every drug available.

Jordan maneuvers the downtown core every weekend to score drugs and remain on a bender for days, referring to himself as a “weekend warrior.” While wandering the streets in his spare time, he’s seen people get shot and he’s seen people attack each other over the drugs they carry. He said Spokane, by far, is the worst place he’s been . Nobody cares about each other, no one takes care of themselves, and the drugs that corrupted the area have made people “selfish,” he said. Those who aren’t addicted treat the people downtown much differently, he said, even if it appears they want to help.

“The only thing this town cares about is Expo ’74 and that Hoopfest,” Jordan said. “Sometimes there’s nowhere to go. … If you stay somewhere (for treatment) and in the middle of your stay the insurance decides they can’t cover it, you’re out. … It’s no accident.”

Trey, who is “couch-surfing” between homes and temporarily living in a shed, said he once had a job at a local gas station for a month. The human resources department did a background check and decided to terminate him. He said every time he tries to somehow advance his life, there’s always another obstacle in the way.

“It’s really kind of defeating at this point,” Trey said. “And a lot of people that are in similar situations as me are at rock bottom and starting from square one or just trying to do good.”

Trey came from a family that struggled with addiction.

“The enemy will nag at you every day to remind you that (addiction) is out there,” Trey said. “And to take the easy way out … nobody wants to take the easy way out. I don’t, at least. I want to progress and get better.”

Two days before Trey and Jordan sat on the street openly using drugs, a young kid fell “flat on his face” at the 7-Eleven store at Second Avenue and Division Street and overdosed, Trey said. He watched the entire thing.

“I’m not sure if he died. But I do know that the ambulance came, and before that he had been ‘Narcanned’ twice and wasn’t coming back. That was pretty rough,” Trey said. “I’ve seen people defecate right in the middle of the street with no shoes on. … Or you walk by and you see a guy with a needle in his arm and bruises and scabs and abscesses all over his face and body and his legs.”

That same day in May, 36-year-old Laura pushed her back against the 7-Eleven as she lit a foil just feet away from where a person overdosed 10 minutes earlier.

Her husband, Daniel, had helped her stay sober for seven years until he died in 2022. Laura then relapsed.

“Once he passed, I had no one else,” she said. Laura was living with Daniel’s mother for a while, but left and became homeless.

“I have depression, bipolar, anxiety. … The wonderful joys of it all … I’m not ready to get clean, but I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired,” she said. “You have to be ready to quit. You can’t be forced into it. You have to be ready.”

The worst part about getting clean for Laura is the withdrawals. It’s like having the flu, but the symptoms are 10 times worse, she said. To get fentanyl to keep the symptoms away, she trades items with others on the street or panhandles. But she gets sick often, since she can’t afford the pills.

Administering Narcan to fellow users when they overdose is a typical day, she said. In what she calls a “ritual,” she administers the naloxone, splashes cold water on their neck and calls 911.

“We are just people; it’s not like we want to be here,” she said. “Everyone has their own story.”

Jordan, however, refuses to let himself “get dope sick,” because he wouldn’t be able to look at himself in the mirror, he said.

As he stood on South State Street facing a multitude of people walking in and out of the House of Charity shelter, tears began to stream down his face. Jordan quickly smeared the tears from his eyes with the sleeve of his jacket, covered in holes and stains.

“I started doing drugs so young I don’t know what it’s like to live,” Jordan said. “I don’t know why I’m crying. I’m sorry.

“I don’t want to use every day. I don’t want to be like that.”

Slinging Narcan

Anne Raven, the integrated medical services manager at the Spokane Fire Department, has been “slinging Narcan since the ’90s,” she told an opioid seminar in April at Gonzaga University.

“I’ve never seen anything like this. It scares me as a mom and it scares me as a citizen,” she said of the opioid explosion. “It’s terrifying.”

Overdose calls can range from six a day into the double-digits, she said. And while the fire department will respond to every one, they also are responding to fires, water rescues and car accidents.

“That’s six times a day an engine is flying down the street, lights and sirens. Six times our resources get tied up,” Raven said. “I don’t say that because an overdose is any less important. But we just don’t have more resources. We don’t have more fire stations.”

More than half of naloxone administrations occurred in the downtown core of Spokane and surrounding areas, including the East Central Neighborhood.

In February, the fire department recorded 68 people treated with Narcan. In March, they recorded 80. Then it was 84 in April, and 91 in May.

In just one day in April, the department responded to eight overdoses within the city limits in five hours and another overdose in the evening.

Dr. Bob Lutz, a former Spokane County health officer, showed a 42-slide PowerPoint presentation to the Spokane City Council’s Public Safety and Community Health Committee in March about drug overdoses in Spokane County. Lutz outlined data showing the county’s opioid death toll surpassed Washington’s statewide average in the years 2021 and 2022.

Spokane County saw a 2,000% increase in synthetic opioid deaths between 2019 and 2022, Lutz told the City Council.

Data from the Spokane County Medical Examiner’s Office shows 11 recorded fentanyl-related deaths in 2019. In 2023, the office recorded 194 fentanyl-related deaths . The same drug – fentanyl – was detected in 64% of all accidental overdoses last year, the medical examiner’s report showed.

In the last few years, there typically have been four to five times more drug-related deaths than those killed in vehicle collisions, according to the medical examiner’s report.

“The shift from other drugs to fentanyl in Spokane arrived between 2018 to 2020,” said Spokane County Medical Examiner Dr. Veena Singh. “When I started my career, it was heroin. Then oxycodone. Then diverted fentanyl, stolen from hospitals. Suddenly it exploded and took over everything.”

It’s much more complicated to track specific overdoses, because sometimes a body comes to the morgue as a suspected overdose, but the cause would later be determined as a heart attack brought on by long-term use of opioids, Singh said.

The same is true for dispatch calls. Police, fire and the behavioral unit may not know the call is an overdose until they arrive on scene.

“Stimulants can cause heart attacks or strokes. Existing disease can predispose them to toxic effects of drugs or enhance it,” Singh said. “But we do have a lot of young people who are still dying without chronic diseases.

“People will turn to fentanyl because they run out of their medication, but still have pain. And there’s no quality control on making pills. There’s no way for us to know if people are developing tolerance because we just don’t know how much they’re consuming.”

The medical examiner’s office caseload is up more than 15% over last year, and last year was up 15-20% from the year before.

“Fentanyl is driving a lot of our accidental deaths,” she said.

‘Dirty junkie’

Spokane resident Sarah Spier was living the Hollywood dream in 2006 when she caught her big break at age 18. She had just finished working as a makeup artist on the Academy Award-winning film “No Country for Old Men.”

And then her boyfriend shot her up with heroin.

She spiraled.

There was no “rational” part of her thoughts that could make her stop.

“My brain was hijacked,” Spier said. “It became a compulsion. Nothing else matters when you’re that far down. It takes time, support and resources.”

One day in 2010, her mother had a gut feeling something was wrong. She found her 22-year-old daughter naked on a bed and overdosing in a known drug house, bleeding from the needle marks in her arm.

“I went into a comatose state and almost died. And my mom saw the way the hospital staff was treating me. She pulled out her phone and showed them pictures of me before my addiction and said, ‘This is my daughter,’ ” Spier said. “I was full-blown shooting drugs in my neck, had track marks everywhere. I was the person people would have called a ‘dirty junkie.’ ”

Spier has made it her mission to educate people about substance use disorder through her foundation, Follow the Poppy. Spier is a certified recovery coach with experience working with Medicaid to make informed drug policy decisions, according to her website.

The problem with the opioid crisis, she said, is that once a part of the system isn’t working correctly, it drags the rest down with it.

“You pay for what you prioritize. Until we start to prioritize the opioid crisis, it’s going to continue to get worse,” she said. “You see that because of how easy it is to get the drugs, but then you also don’t have all the aftercare support.”

Spier said another problem rests with those who use Medicaid. Some detox centers will take both private insurance and Medicaid, but the reimbursement rates for Medicaid “tend to be significantly lower as opposed to commercial,” she said, which results in treatment centers being unable to pay their staff.

“It’s not cost-effective. People who have Medicaid should have the same type of forms of care as people with private insurance,” Spier said. “There is a real disparity.”

Ryan Chaffins, executive director of Rebuilt Treatment and Recovery, said most detox programs take about five days. With how strong the effects of fentanyl are becoming, though, those five days aren’t enough.

Withdrawal symptoms, he said, can last for two weeks.

“Take people into detox, that’s five days, and then other programs are 28 days, which is a substance -use program,” Chaffins said. “Someone may only be eligible to do five days because of insurance. It’s a mill of people detoxing and going right back into their environment. If it’s pointless to have a detox and send them back, then it’s pointless to have the detox altogether.”

It also takes time to change behavior and patterns that homeless substance users have, Chaffins said, so five days of detox and 28 days of inpatient treatment isn’t enough.

“To say a short detox is enough to make someone want to change everything, is not the way it is,” he said. “In my experience, the bigger problem is longer-term treatment. Ninety days, sober living and intensive outpatient care is getting missed.”

Spier said if she had only received 28 days of inpatient care, she’d be dead. Her mother spent thousands on her treatment and supported her through her recovery for 14 years.

But not everyone has that type of familial support, Spier said – some who are homeless don’t have family at all.

Traci Couture Richmond, executive director at Spokane Teaching Health Center, said there is a lack of practitioners who specialize and truly understand substance use disorder. She knows this, she said, because her sister died of an overdose in 2021.

Agreeing with Spier, the 28-day model is not enough, Richmond told attendees during the opioid seminar at Gonzaga.

“My sister was ready to get treatment but was turned away. She had taken 240 hydros, 90 oxy and 15 Percocets within a two-week period. Her doctor said to her, ‘Are you trying to kill yourself?’ and ‘Here is a referral.’ There was no follow-up,” Richmond said. “Then she took 19 Ambien and downed it with whiskey. She’s sent to an emergency room. They (held) her for 72 hours and let her go. This is the cycle we are dealing with.”

More than a crisis

While Spokane is a caring community, it doesn’t make it immune to drug crises. A visitor may never know the extent of addictions, but the city “passed a crisis a long time ago,” said Spokane police Lt. Rob Boothe. He said it’s by far the worst such epidemic the area has faced, even in comparison to crack cocaine of the 1980s. Cocaine comes from a plant, which limits manufacturers to a growing season. Fentanyl is synthetic, he said.

“It can be mass-produced on a scale above and beyond what they could do with crack cocaine,” Boothe said.

The Spokane Police Department seized 41,747 fentanyl pills from January to May of this year, according to their data. That landscape has changed substantially, Boothe said. Addicts four years ago would pay up to $10 per fentanyl pill. Now, pill prices are as low as a dollar.

Typically, illicit fentanyl is bought in pill form, placed in foil with tobacco or other substances and then smoked.

Manufacturers of fentanyl pills will press the pill with other binding agents like acetaminophen, Boothe said. Medically issued fentanyl, meanwhile, won’t be mixed with acetaminophen, so when tested, forensic labs are able to determine if the pill was made illegally.

“When you go to Rite Aid (and) need that aspirin bottle, now they have to take it out behind the glass shelf and laser-code it. I think we’re literally a decade away from everything being locked up,” he said.

Not every person who uses fentanyl will die, Boothe said. Except it only takes one person to get a “hot batch” and overdose.

Referred to as the “chocolate chip cookie method,” pill pressers mix the fentanyl and the binding agent together and begin to press the drugs with no measurements as to how much fentanyl powder is going in each pill.

“It’s just like if you get a chocolate chip cookie,” Boothe said. “If you crack it into four pieces, one piece might have one chocolate chip and one piece might have six.”

The extra “chocolate chips” would be unknown to the user, he said, leading to an overdose.

Boothe compared using fentanyl to Russian roulette, “putting a bullet in the cylinder, spinning it and putting it to your head.”

The influx of opioids has become such a problem, some drug dealers in Spokane have direct ties to Mexican cartels, Boothe said.

“We’re literally one step away from a cartel. Some of our investigations are directly linked,” he said.

U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Washington Vanessa Waldref said although she can only prosecute in Eastern Washington, her office is working with other federal districts to go after drug cartels operating across jurisdictions. Those investigations, however, take significant time, she said.

“It takes a lot of effort to monitor drug trafficking organizations. They’re very smart and very driven by how they can sell. … They are constantly changing their strategies, so law enforcement has to be agile and responsive. It’s difficult work to seize and remove all of the dangerous narcotics,” Waldref said. “The quantity is also so vast.”

Part of the reason combating an opioid crisis is so difficult is because most of the drugs are made in a lab, making them cheaper and more addictive, she said.

“The Spokane area has been hit particularly hard,” Waldref said. “The death and tragedy that we are witnessing is staggering.”

The Spokane County Sheriff’s Office last year seized a commercial-grade pill press capable of stamping 17,000 illegal pills an hour, a second pill press, 446 grams of meth, 2,057 grams of presumed fentanyl, 660 grams of heroin, 206 grams of cocaine, three kilogram-sized packages presumed to contain more fentanyl and $57,000 in cash.

Boothe said some people may think one pill press isn’t “that big of a deal” – but when it produces such a high volume of illegal pills, it “floods” the community.

“The volume of narcotics in this community – we will never put the toothpaste back in the tube,” Boothe said. “The market, it just creates itself. I don’t think people have an idea of just how flooded the community is. It’s not just the folks downtown. It’s everywhere.”

‘Scraping by’

The CARES team of the Spokane Fire Department takes referrals from any first responder after a 911 call, and the type of follow-up depends on why the person was referred.

Contact is made from one to three days after the first call, said Sarah Foley, the social response manager for the fire department.

If someone overdoses, their addiction might not be the first thing they want to work on with the CARES team. It depends on what their most pressing needs are at the moment, such as housing or mental health treatment, Foley said.

Their program is small and “niche,” Foley said, but struggling with staffing and the need to provide comprehensive services.

The city intends to invest $500,000 from Washington’s opioid settlement fund into CARES, which would add three employees to the team, according to a city news release.

“We are very excited to get the funding, because we’ve literally been scraping by,” Raven said in May.

But the team needs long-term funding, too.

“We have operated all this time with one paid social worker. She oversees students doing internships, too. We can add more, but we have to keep paying them,” Raven said. “We deal a lot with the elderly population, too.

“CARES always comes in and does an assessment. And with the added burden of the fentanyl crisis, it’s so much. It’s not a problem that will get fixed overnight. We need to continue to fund it.”

While most say funding is necessary, the barriers still exist after CARES does everything they can do.

Foley said finding detox availability can sometimes be a challenge if a day is busier than normal, leading to a gap between detox and long-term treatment.

“Some centers have care navigators to work with, but for the people who can’t get treatment the moment they’re ready, it delays the process of change,” Foley said. “It’s a risk, depending on what they’re using.”

Just days can set someone back – especially while trying to make changes in other areas, like mental health or housing, Foley said. When time is of the essence, small barriers can push a person into the state they were in before they made the decision to seek treatment in the first place.

“Some change their minds because of the delay,” Foley said. “They’re like ‘Oh, it’s too hard right now’ but I think they’ll get there eventually.”

Spier has tried to help people with substance use disorder in Spokane find a facility that works for them. It doesn’t always work out the way it’s intended, she said.

“They tell you to call back,” Spier said. “And then you have people who die.”

Tennille O’Blenness is the administrator for the Isabella House, a nonprofit six-month inpatient program that serves women with children and pregnant women with substance abuse disorder.

Getting a bed for treatment, she said, can take months. Staff doesn’t let people actively withdrawing from drugs or alcohol into the house unless going through detox first because there are children around. It’s what makes the Isabella House unique.

“On top of it, moms are scared to go into detox because they don’t want to suffer from withdrawal,” O’Blenness said. “It’s a harder situation to address, getting them here entirely. If we can get them here, we can have a positive effect. We also have a higher abort-treatment rate in that first week.”

O’Blenness agrees the gap between detox and long-term treatment is problematic.

She recalls patterns where incoming patients will continue to possess drugs after finishing detox, which signals to O’Blenness that the patient’s possessions aren’t getting checked. The Isabella House may not always be notified when one of their patients is released from detox, either.

“Families don’t realize they still have drugs, and they’re using in between,” she said. “That has been the experience. I’ve done this for 12 years. It’s frustrating and sad. I see the aftermath. So I’m grateful they make it here, the people that do.”

Ryan Kent, the executive director of Spokane Treatment and Recovery Services or STARS, said to receive treatment, the person has to have some type of insurance. Most of the time they can get it set up the same day, he said, although “there are some circumstances that can be complicated.”

STARS now has 38 beds in its treatment center after adding more staff.

Bed space fluctuates, because detox can range from a couple days to more than a week, Kent said.

Pioneer Center East, at 3400 W. Garland Ave., has 53 beds for residential inpatient treatment for men.

Spokane Regional Stabilization Center, owned by Pioneer, has 46 beds.

The dream clinics

One solution may lie with Suboxone, the drug that the behavioral unit has on hand during their shifts. Krissa Orlowski, an assistant teaching professor at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine and part of the MEDEX Northwest Physician Assistant Training Program, believes that more education about Suboxone, more investment into the drug and more Suboxone clinics are a start to the solution surrounding substance use disorder.

The difference is it’s a partial “antagonist and agonist,” meaning it attaches to neuroreceptors and kicks other opioids off the brain’s receptors. Opioids cause respiratory side effects, something Suboxone doesn’t. The person has to be in moderate withdrawal for it to work, which is why the behavioral unit hopes to administer Suboxone following Narcan, since Narcan sends someone into withdrawals almost immediately.

Medical professionals used to only use Methadone, another withdrawal management drug. Methadone clinics have much more global support since the treatment was considered “tried and true,” Orlowski said, but because Suboxone is so new, there aren’t a lot of clinics that use it .

Methadone clinics also require a patient to go into the clinic every day for constant treatment, which can be beneficial to those who need constant in-person support and management. But many don’t have access to transportation or live far from the clinic.

With Suboxone, a doctor can prescribe a supply to send home to the patient, and Medicaid and Medicare cover it “quite well,” Orlowski said.

But not everyone has the ability to make it to a pharmacy all the time, she said – so having Suboxone clinics with well-supported case management and widely available prescriptions for the drug is a start.

Some places in Spokane offer Suboxone, like Compassionate Addiction Treatment, a recovery center that offers medical treatment, peer support and case management. There are some physicians who are licensed to prescribe Suboxone within the county.

“Suboxone clinics are the dream for substance use disorder,” Orlowski said. “But the thing we know beyond a doubt is if you don’t address the circumstances that got them there in the first place, their chance of relapse is much higher.

“People are driven to addiction by adverse events. And once they’re addicted, the things they have to continue to do are trauma-inducing. Like homelessness, food insecurity. If we are just medicating the issue, we are not totally helping.”

Spokane County has big plans for the opioid settlement funds it expects to receive from state lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors, and has devoted its initial disbursements totaling $7.2 million toward some of those existing gaps in the regional treatment network.

“We looked at all of these areas, medium treatment, long-term treatment, comprehensive engagement, gap areas and supportive housing,” said Justin Johnson, Spokane County community services director. “The county has looked at a wide swath of areas that hit everything that the community is looking for, but more effectively addresses areas where the largest gaps are, where insurance or other providers are not covering.”

In recent years, Washington has been awarded more than $1.1 billion in opioid court judgments and settlements. Roughly half of it will be dispersed to local jurisdictions. Spokane County expects to receive around $17.5 million divided in installments until 2038.

The county commissioners have agreed to put $5.2 million of the money received so far toward a proposed expansion of services at the Spokane Regional Stabilization Center, a 45-bed medical and mental health emergency clinic aimed at providing care for those who often cycle through stays at the jail and local emergency rooms without receiving addiction treatment.

At present, only people escorted to the facility by a law enforcement officer and who meet certain requirements are able to access the facility. Ashley Magee, an integrated behavioral health care manager for the county, told the Spokane Valley City Council in March that 1,563 people were served by the facility in 2023.

Johnson told The Spokesman-Review last month $5 million of the county’s settlement funds will go toward capital improvements at the facility, with the intent of expanding services to include crisis relief and stabilization for walk-ins and referrals, bolstered mental health and substance use treatment, and more extensive withdrawal and detox management care.

The latter is one of those gaps in the treatment system Johnson hopes the investment will help fill. Those who go through detox or receive withdrawal treatment may not always go on to an inpatient facility, and there is a need for more detox and inpatient facilities in the region. Having those services in one location would be beneficial in getting those already at the facility into a treatment plan.

“That is the biggest challenge we have with individuals,” Johnson said, “is finding a place that provides a comprehensive and safe environment so that they can be encouraged to remain in care longer.”

The remaining $200,000 allocated to the center will help cover its ongoing annual operation costs.

‘We will pay for this, one way or the other’

While treatment is a priority, so is reducing the stigma of those with substance use disorder for those on the front lines.

When Spier’s mother showed the hospital staff the pictures of her daughter to humanize her all those years ago, she said it seemed to make her “more of a person” in their eyes, even though she was already in need of compassion for a disease and a compulsion.

Orlowski said some providers in Washington didn’t even want to do Suboxone training because it “created a lot more work for them” for a population they didn’t want to deal with.

“When your body is telling you you are going to die from withdrawal, you are going to lie and steal to survive,” Orlowski said. “People don’t want to go the extra mile for a population that’s difficult if there’s barriers there in the first place.”

Typically, people will blame those with substance use disorder and wonder why they’re not immediately changing their lives or focusing on treatment. People also say addiction is just a moral failing – but that’s inaccurate, said Nicole Rodin, a clinical assistant professor of pharmacotherapy at the Washington State University College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

“The stigma within people, the public perception and stigma within access to treatment can be a huge barrier in improvement,” Rodin said at the April opioid seminar. “The stigma is that they are dangerous, unpredictable, homeless or dirty and they made a choice. … But what might start as a choice, doesn’t end as a choice.”

Spier said she believes Spokane is a community that cares. The community needs to remember that people with substance use disorder do not think rationally. Their brains begin to function differently, and they need empathy rather than threats or disdain.

“When I sit back and remember, there was nothing rational or understandable about being a heroin addict,” Spier said.

As for Spokane, she said it will only get worse unless there is a revamp of the system itself.

“We are either going to pay for funding through supporting treatment agencies or we are going to end up paying through incarceration and loss of productivity our city will face,” Spier said. “We will pay for this, one way or the other.”

That day in February when Ellinwood helped Adam, she acknowledged how cyclical the process of substance use disorder is. There are failures in housing, in mental health resources and just an issue with access to services in general, she said.

“It’s getting worse,” Ellinwood said. “There’s just a lot of systemic failures happening.”

As paramedic Jordan Johnson drove near a downtown homeless shelter, he said he has seen a lot of things he tries to distance himself from, things that a person who isn’t a first responder would never have to see in their entire life.

“But I don’t disconnect too much. I have compassion,” Johnson said. “I do my best to treat them with empathy. They are human beings.”

S-R reporter Nick Gibson contributed to this article.