A tale of two middle schools: Spokane’s Salk Middle School enforces phone prohibition this year, ‘a marked change’

Salk Middle School Assistant Principal Sarah Pooler walks by a table of students playing Uno on their lunch break, left to right, Tyler Prosser, 14; Zoe Jackson, 13; Puniyo Hoard, 13; and Ofelia Gutierrez. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

At lunch, Salk Middle School assistant principal Sarah Pooler is a bloodhound, scanning the bustling cafeteria for a newly established contraband at her school this year: cellphones.

Conversations around cellphone restrictions in schools have been underway at the state and district level, as well as a near-constant topic in debates for school-related elected officials. As entities mull their policies and consider guidance for schools, some are forging ahead. They tighten cellphone policies on their campuses in the hopes of bettering their students’ academic focus and encouraging in-person interactions with their peers.

Salk Middle School is one such school where principals cracked down on cellphone use, this year requiring students to keep devices out of sight during school hours, including between periods and lunch. From the hours of 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., phones are absent from the Indian Trail school serving 600-some kids.

“Middle school is a great time to grow socially and academically. Phones are not a part of that,” Pooler said.

Two miles south in the Audubon Neighborhood, Glover Middle School is taking similar strides. Its policy this year allows for phone use between periods, at lunch and before and after school. Each teacher polices phone use differently in classrooms, employing a “red light, green light” system to tell students when phones are permitted.

“The vast majority of kids are great at following the policy,” Glover principal Mike Stark said, adding there are a handful of students he calls “nonresponders,” who regularly defy phone restrictions in class.

A Salk-esque modification to phone use is nigh for 500 pupils at Glover; Stark will next year enforce a full prohibition in classes, between periods and lunch.

Stark plans to include a pouch in each kid’s binder for their phone. Much like at Salk, phones are still accessible to kids. By keeping their phone on their person, students don’t feel deprived, both principals said, and maintain autonomy.

“The fight is possession,” Stark said. “For many of them, that phone is like their $1,000 lifeline.”

But to Pooler, “Out of sight is the magic.”

Posters hung around Salk’s hallways to remind students of the policy; If a staff members spot a phone, they collect it and bring it to the front office where students can collect it when the final bell rings.

Pooler said the restrictions have reduced behavioral issues and associated discipline; the “drama, gossip and threats” that proliferate social media stay there, rather than following pupils onto campus.

“They’re not continuing the drama during the day,” Pooler said.

“It’s a marked change.”

Changes are also apparent in kids’ behaviors with each other. At Salk’s lunch time, kids stampede into the hallways on their way to eat, ears notably absent of earbuds. Most walk in pairs, many linking arms. Their eager voices bounce off the walls as they spill into the cafeteria to claim their seats. Some conversations are sprinkled with swearing, but they’re talking, nonetheless – without the intervention of cellphones.

Few kids sit alone, and none has a phone out, per the policy. Some play card games, show off their schoolwork or get started on homework.

In the second half of lunch, the school hosts tournaments in pingpong and volleyball, not directly correlated to keeping kids’ idle hands from reaching for their phones, but working toward the same goal of “building community,” Pooler said.

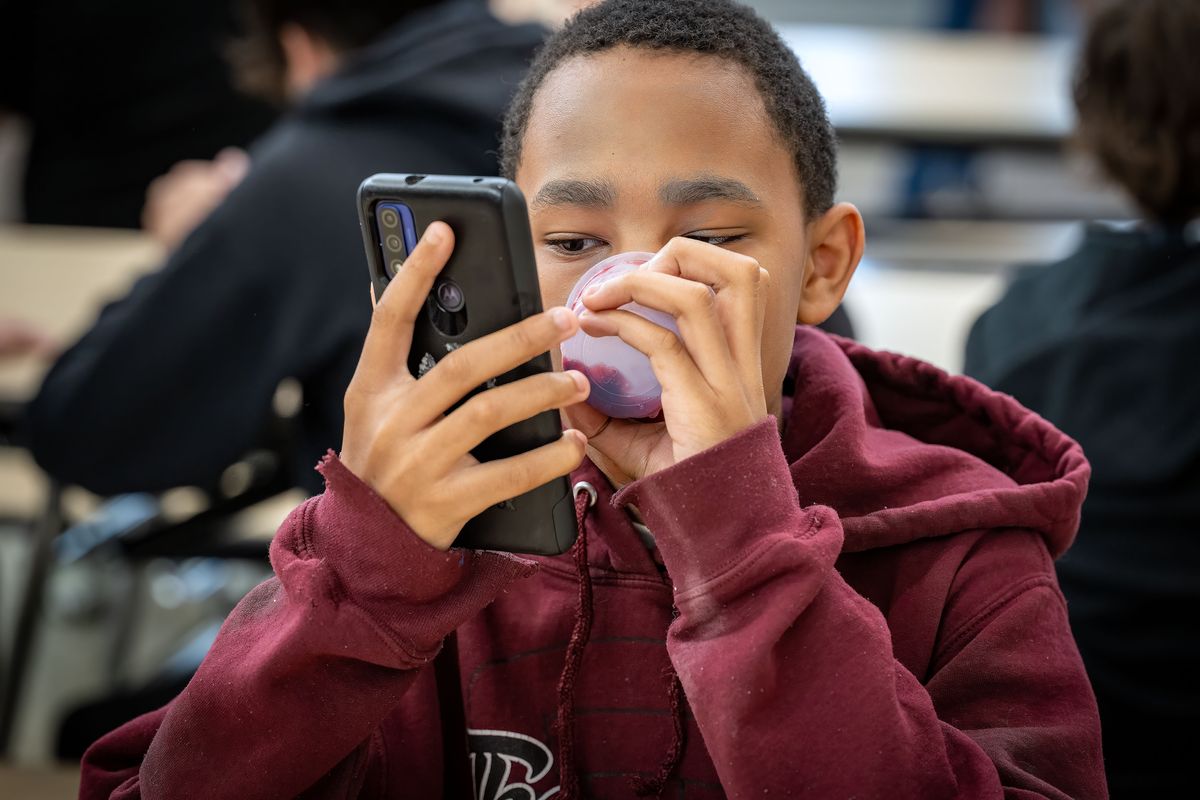

At Glover, it’s the same stampede of preteens flooding the cafeteria, though many have headphones in, sometimes in their ears as they converse with peers. Most talk with each other, clutching their phone at their side or showing it to a friend. Some peel off from the crowd; they stand with headphones on, neck bent 90 degrees staring at their phone in their hands, thumbs busy scrolling or tapping.

Some spend the whole lunch this way, seated by themselves while they scroll. Even in groups, phones are present. When they buzz, kids check it, seemingly a reflex that removes them from the human interaction before them. Many sit in pairs, watching the same phone together, laughing over TikTok videos and Snapchat messages.

Some students have had their own smartphone since they were 5 years old, they said.

Between five students at Glover, they spent an average of 6½ hours on their phones every day that week; TikTok and Snapchat are recurring characters for the most frequently used apps on many of the girls’ phones, according to the screen time record accessible on iPhones.

“I go on my screen time a lot; normally my daily average is, like, 16 hours on my phone,” said sixth-grader Abigail Mendez, though her time was much lower the day she compared her screen time with her friends.

In May, her phone recorded her screen being on for 212 hours, or more than eight days.

“That’s crazy,” she said.

Abigail recalled her parents once instructing her to leave her phone face down on their coffee table for a morning.

“He was like, ‘Just leave it alone until we have to go to school,’ ” she said. “And all you could hear was just notifications from Snapchat, just over and over and over again.”

The repeated pinging lured her, though she stayed strong that morning.

“How I reacted was like, ‘I have to respond to them, they’re going to think I’m dead,’ ” she said. “ ‘Cause I’m a fast responder.”

Phone attachment, or addiction depending on which student you ask, runs deep. This is true when abstaining throughout the school day in Salk’s case. Salk students said they often get on their phones as soon as the final bell rings, sometimes to check social media, sometimes for school-related functions like checking their bus arrival time on the Zum app.

“If we were allowed to have our phones, I would probably be on my phone, like, all the time,” Salk seventh-grader Sophie Lopez said.

Salk seventh-grader Kinley Ballestrazze noticed as her phone, tablet and computers became increasingly present in her life; it’s been a drain on her energy, coupled with the fact she feels her phone use has “ruined” her sleep.

“When I was younger, I didn’t have electronics. I would usually go outside and leave my phone inside until nighttime and then I, like, watch shows,” she said. “I used to go outside a lot, and I used to be a really energetic kid, and now that I’m on my phone a lot, I don’t have a lot of energy.”

“I was more productive as a child,” Sophie said, nodding solemnly.

“ ‘Cause we didn’t have electronics,” Kinley insisted.

Some phones have mechanisms to restrict time spent on certain apps. Glover sixth-grader McKenna Sonnett said she limits time spent on TikTok, but she knows the passcode required to bypass the limit and often skips the warning when her time is up and snoozes it for 15 minutes.

“That ends up happening for, like, three hours,” she said.

Eventually, the endless scroll and deluge of notifications bores Abigail, she said, but she doesn’t have an alternative to her phone.

“If I’m on it too much, I’ll get really bored and I’ll wanna do something else, but I have no idea what to do,” she said, her friends agreeing.

Students frequently interact with content or behaviors they know to be “toxic,” they said, like unachievable beauty standards they see on social media and avoiding sleep to keep scrolling.

“I feel like certain social media gives you a bad body image of yourself,” said Emily Coon, a sixth-grader at Glover.

“There’s always a lot of people arguing on TikTok; it’s funny sometimes, but when it’s you arguing, it’s annoying,” said Glover sixth-grader Addis Lual.

Phones are a distraction in class, some Glover students said. A fear of missing out and need to check notifications or social media often diverts their attention from their studies to their phone.

At Glover, students said their peers have been known to use phones as distractions in all sorts of cellular mischief.

“It can be chaotic,” seventh-grader Kiley Cederblom said. “Some kids play loud noises on their phones, some kids think they’re funny and take pictures of you.”

Some students set alarms to go off in the middle of class.

“There’s this kid in our class that had their phone ringing and it had, like, bad words in the ringtone,” Abigail said.

Salk’s Sophie said without the no-phone policy, she’d use her phone much more in and outside of class. It’s more entertaining than school, she said. And without the policy, “there wouldn’t be as much learning,” she suspected.

“You’d get really distracted and can’t do work,” Sophie said. “You’d be on your phone texting or watching TikTok or something, and then you won’t be doing your work.”

Recalling an era of Salk with looser restrictions, seventh-grader Olivia Biles said she saw kids fully disengaged from their teachers in favor of their phone.

Regardless of the policy, kids noted that their phones are ever-present in their relationships with each other. Kids often scroll their devices in tandem, sometimes pausing to show the other something.

“You go to a sleepover or something and you feel like you’re both on your phone too much and you’re, like, alone,” Emily said.

Abigail noticed a similar pattern with her family, as well as friendships. Reducing her phone use would be easier, she said, if others did it too.

“I’ll get off (my phone), ‘cause I get bored of it, and then I go downstairs to my family and all of them are just on their phones,” Abigail said.

At phone-free Salk, kids described the opposite side of the same coin. They found they bonded more without phones as a mediator.

“I also feel like when you’re without your phone, people talk more,” Kinley said. “If they did get to know each other, they could actually get their phone number and then text and then talk over school.”

Pooler said at Salk, she hasn’t had a parent complaint about the policy. If anything, she said they appreciate it, as it makes cellphone management at home an easier task. Stark said he’s heard a common what-if in the cellphone prohibition conversations from parents, how do students reach their parents in an emergency, and vice versa?

“I would want parents to know during an emergency as soon as we know the kids are safe and the building is safe,” Stark said.

At Salk, phones stay on students’ person, and Stark plans the same for Glover. As such, they’re accessible during emergencies. As for families reaching their kid at school, Pooler reminds parents of the standard operating procedure pre-cellphones: call the front office.

“Pretend it’s the ’90s,” she said.

Pooler said the policy change improved the environment of her school; she thinks restrictions would also be a good fit at other schools. Salk has among the strictest cellphone policy of Spokane Public Schools’ middle schools, joined by Flett in barring use during lunchtime.

The policies at Chase, Shaw, Sacajawea and Yasuhara middle schools are similar to Glover’s in allowing use between periods, lunch and before and after school.

Superintendent Adam Swinyard said the district is in the process of reevaluating its overarching phone policies, and anticipates “clear and consistent guidelines” by the beginning of next year.

“One of the things that we’ve noticed and we’ll be continuing to talk about in the foreseeable future is just the level of disengagement that we’re seeing in kids, and we saw that prepandemic and certainly, it’s been exacerbated postpandemic,” Swinyard said.

Salk’s Sophie said while she still uses her phone frequently outside of school, she tries to consider her school’s regulations when moderating her own screen time and phone usage. Schools play an important role in reducing cell usage in kids, she said.

“I try to limit my own screen time at this point now, because the school limits it, so I limit it,” Sophie said. “I’m just like, you know what? The school is actually kind of cool.”