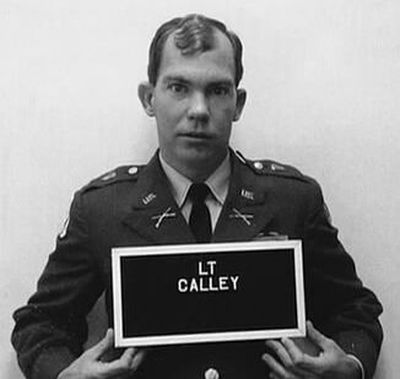

William Calley, Army officer and face of My Lai Massacre, is dead at 80

William L. Calley Jr., a junior Army officer who became the only person convicted in connection with the My Lai Massacre of 1968, when U.S. soldiers slaughtered hundreds of unarmed South Vietnamese men, women and children in one of the darkest chapters in American military history, died April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Florida. He was 80.

The Washington Post obtained a copy of his death certificate from the Florida Department of Health in Alachua County. His son, Laws Calley, did not immediately respond to requests for additional information. Other efforts to reach Calley’s family were unsuccessful.

The Post was alerted to the death, which was not previously reported, by Zachary Woodward, a recent Harvard Law School graduate who said he noticed Calley’s death while looking through public records.

Although he was once the country’s most notorious Army officer, a symbol of military misconduct in a war that many considered immoral and unwinnable, Calley had lived in obscurity for decades, declining interviews while working as a jeweler in Columbus, Ga., not far from the military base where he was court-martialed and convicted in 1971.

A junior-college dropout from South Florida, he had bounced around jobs, unsuccessfully trying to enlist in the Army in 1964, before being called up two years later. As the war escalated in Vietnam, he found a home in a military that was desperately trying to replenish its lower ranks.

Calley was quickly tapped to become a junior officer, with minimal vetting, and was soon promoted to second lieutenant, commanding a platoon in Charlie Company, a unit of the Army’s Americal Division. The company sustained heavy losses in the early months of 1968, losing men to sniper fire, land mines and booby traps as the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched coordinated attacks in the Tet Offensive.

On the morning of March 16, 1968, the unit was airlifted by helicopter to Son My, a patchwork village of rice paddies, irrigation ditches and small settlements, including a hamlet known to U.S. soldiers as My Lai 4. Over the next few hours, Calley and other soldiers in Charlie Company shot and bayoneted women, children and elderly men, destroying the village while searching for Viet Cong guerrillas and sympathizers who were said to have been hiding in the area. Homes were burned, and some women and girls were gang-raped before being killed.

An Army investigation later concluded that 347 men, women and children had been killed, including victims of another American unit, Bravo Company. A Vietnamese estimate placed the death toll at 504.

For more than a year and a half, the details of the atrocity were hidden and covered up from the public. A report to headquarters initially characterized the attack as a significant victory, claiming that 128 “enemy” fighters had been killed. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the top commander in Vietnam, praised American forces at My Lai for dealing a “heavy blow” to the Viet Cong.

Meanwhile, Ronald Ridenhour, a helicopter gunner who was not at the scene but had heard of the killings weeks later, did his own probing. While on home leave nearly a year after the massacre, he began writing letters to top political and military leaders about the bloodbath at My Lai – providing information that was credited with sparking official investigations.

Backed with photographs and witness testimony, the Army charged Calley with premeditated murder days before his scheduled discharge.

Although a four-paragraph Associated Press article appeared in September 1969, providing Calley’s name and reporting that he was being held for allegedly murdering an unspecified number of civilians, a more complete picture of the massacre was not revealed until that November, through articles by investigative reporter Seymour M. Hersh.

Acting on a tip by an antiwar activist, Hersh worked exhaustively to track down Calley. He finally located him in the unlikeliest of places for a man facing court-martial for what at the time was believed to be 109 murders: at the senior officers’ quarters of Fort Benning, now called Fort Moore, in Georgia.

Hersh’s articles, distributed to newspapers around the country by the independent Dispatch News Service, received the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting, shocked a nation that was already divided over the Vietnam War and thrust Calley into the national spotlight.

Almost from the very beginning, Calley polarized Americans who variously deemed him a war criminal or a scapegoat, a mass murderer or an inexperienced officer made to take the fall for the actions of his superiors. Defenders argued that he had been forced into a brutal conflict with an often invisible enemy, then blamed for the horrors of the war.

To some, he seemed like a convenient target for military prosecutors, the lowest link in a chain of command that included Capt. Ernest Medina, who was accused of bearing overall responsibility for the attacks, and Maj. Gen. Samuel W. Koster, the highest-ranking officer charged with trying to cover up the massacre.

Calley was convicted of murdering at least 22 noncombatants and sentenced to life at hard labor, after a military jury rejected his defense that he was just following orders. Amid appeals, he ultimately served about three years, much of it under house arrest.

“My Lai was the absolute low point in the history of the modern U.S. military,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning military correspondent Thomas E. Ricks, whose book “The Generals” traces the evolution of the post-World War II Army.

Beyond the atrocities committed by Calley, Ricks said it was important to remember that “there were 1,000 causes here, bad people doing bad things up and down the chain of command,” including the “second grave sin” of the coverup.

“My Lai forced a reexamination of the U.S. Army,” Ricks noted, referring to its central role in later studies about revamping military professionalism. “It was not just that hundreds of civilians had been murdered, and a score raped, but that the acts of the day were covered up by the Army chain of command.

“The incident was just not the work of a deranged lieutenant,” he continued. “Other officers were aware of what was going on. And the extensive coverup, including the destruction of documents, went all the way up to the rank of general, with two generals and three colonels implicated.”

‘Go and get them’

The attack on My Lai came a month and a half after the Tet Offensive. U.S. soldiers had visited the village a few times, interviewing residents while seeking intel about the Viet Cong, or VC. This time, Medina told his men in Charlie Company, the objective was to strike hard against a community believed to be harboring VC.

Destroy anything that is “walking, crawling or growling,” Medina declared in a pre-mission briefing, according to testimony given at Calley’s court-martial. Asked if that included women and children, he replied that according to military intelligence, ordinary villagers should be at a nearby market. Anyone left behind was either a guerrilla or a sympathizer.

“They’re all VC, now go and get them,” he said, according to trial testimony.

Around 7:30 a.m. the next morning, Calley and his platoon arrived at the village expecting heavy resistance. Instead, they found a quiet community sitting down for breakfast.

Some soldiers thought it was a trap, according to court-martial accounts. Viet Cong explosives and mines had accounted for up 90 percent of American casualties in the previous months. As Calley’s men fanned out, some shot villagers while searching in vain for suspected fighters. Others used grenades to blow apart homes.

Calley’s platoon herded women, children and elderly men into groups. Accounts vary on what happened next: According to Calley, Medina grew irritated by the unit’s slow progress and told Calley to “get rid of” the civilians. Medina denied giving any order to harm civilians, although other soldiers remembered it differently, recalling that Medina made it clear that it was acceptable to “wipe the place out.” A few minutes later, Calley and a fellow soldier, Pfc. Paul Meadlo, were said to have opened fire.

At the court-martial, soldiers described a systematic slaughter of defenseless civilians. Entire families were wiped out by the attack. Witnesses said Calley shot a praying Buddhist monk and, when he saw a young boy crawling out of a ditch, threw the child back in and shot him. Pictures taken at the scene by an Army photographer, Ronald L. Haeberle, provided additional evidence of the massacre and were later published in newspapers and magazines.

The My Lai killings were further exposed in 1969 by Ridenhour. After leaving the service, he wrote to President Richard M. Nixon, Defense Secretary Melvin R. Laird and members of Congress with his findings. An Army investigation ensued, leading to the indictment of more than a dozen men, but several of the cases unraveled before trial or ended without convictions.

In the end, only Calley was held legally responsible for playing a direct role in the massacre. He was convicted on March 29, 1971, after one of the longest court-martials in military history.

“My troops were getting massacred and mauled by an enemy I couldn’t see, I couldn’t feel and I couldn’t touch – that nobody in the military system ever described them as anything other than Communism,” Calley said in a statement to the court. “They didn’t give it a race, they didn’t give it a sex, they didn’t give it an age. They never let me believe it was just a philosophy in a man’s mind. That was my enemy out there.”

The outpouring of support for Calley was captured in a spoken-word song, “Battle Hymn of Lt. Calley” – “Sir, I followed all my orders and I did the best I could/ It’s hard to judge the enemy and hard to tell the good” – that was performed by Terry Nelson and sold more than 1 million copies.

After his conviction, Calley was removed from the stockade on Nixon’s orders and confined to his quarters at Fort Benning. His life sentence was quickly reduced to 20 years and, in 1974, the sentence was halved again, to 10 years, after the secretary of the Army found that Calley “may have sincerely believed that he was acting in accordance with the orders he had received and that he was not aware of his responsibility to refuse an illegal order.”

Later that year, Calley was freed on bail and paroled. He seldom spoke about My Lai, although in 2009 he delivered what was reportedly his first public apology for the massacre, at a meeting of the Kiwanis Club of Greater Columbus.

“There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai,” he said. “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

During the speech, he also said that he had just been following orders, a declaration that irritated critics who questioned whether he had experienced a change of heart.

An ‘average’ schoolboy

William Laws Calley Jr., the second of four siblings and the only son, was born in Miami on June 8, 1943. His father, a Navy veteran of World War II, sold heavy construction equipment. As the business prospered, the family began vacationing at a cottage in North Carolina, and a teenage Calley – nicknamed Rusty for his reddish-brown hair – was given his own car.

Calley was often described by peers and adults who knew him as an “average” American schoolboy: reserved, polite and pleasant but, at 5-foot-3 and 130 pounds, sometimes struggling for attention in school and social settings.

Academically, he was in a downward spiral. He was forced to repeat seventh grade after being caught cheating on an exam. He later spent two years attending military academies in Florida and Georgia before graduating from Miami Edison Senior High School in 1962 in the bottom quarter of his class.

After flunking out of Palm Beach Junior College, he supported himself with jobs as a hotel bellhop and restaurant dishwasher. During a bitter labor strike in 1963, Florida East Coast Railway hired Calley as a switchman and then promoted him to conductor. Among other incidents, Calley once let freight cars get loose and smash into a loading ramp.

Around this time, Calley’s home life grew unstable. His mother was dying of cancer, and his father, who developed diabetes, saw his business fall into bankruptcy. In 1964, William Calley first tried to enlist in the Army but was rejected because of a hearing defect.

He began drifting west and south in search of work. At one point, he was on assignment in Mexico for an American insurance investigator when he walked off the job, saying he was “bored and frustrated” and didn’t understand what he was doing. Calley left for San Francisco, where his backlog of mail began to catch up with him, including a Selective Service notice saying his earlier rejection was being reconsidered.

On his way back to Florida, his car broke down in Albuquerque. He walked into a local Army induction center, explained his situation and enlisted as a clerk-trainee in July 1966. He was soon selected for officer candidate school by a senior officer who took notice of Calley’s brief stints at military academies.

Despite the Army’s acute need for junior officers in Vietnam, historian Howard Jones wrote in his 2017 book “My Lai,” “The Citadel, West Point, and the Virginia Military Institute had been unable to fill the growing demand, and the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) had fallen out of favor on many college campuses. The army immediately needed more recruits from OCS – which opened the door to Calley.”

Calley graduated 120th in his OCS class of 156.

“One thing at OCS was nobody said, ‘Now, there will be innocent civilians there,’” Calley recalled in his 1970 memoir, “Lieutenant Calley: His Own Story,” written with journalist John Sack. “It was drummed into us, ‘Be sharp! On guard! As soon as you think these people won’t kill you, ZAP! In combat, you haven’t friends! You have enemies!’ Over and over at OCS we heard this and I told myself, I’ll act as if I’m never secure. As if everyone in Vietnam would do me in. As if everyone’s bad.”

After his release from military custody, Calley moved to Columbus and married Penny Vick, whose family owned a jewelry shop, in 1976. Smithsonian magazine later reported that their wedding guests included U.S. District Judge J. Robert Elliott, who had attempted to get Calley’s conviction overturned.

Calley and Vick had a son, Laws, and later divorced. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Calley reportedly carried an umbrella at times to prevent photographers from taking pictures of him. He wished, he said, to “sink into anonymity.”

Curiously, his death certificate matched known details about his life – including information on his birth, career, name and nickname – but featured one notable omission. On a line asking if he had ever served “in U.S. armed forces,” the answer given was “no.”

Rae Riiska and Monika Mathur contributed to this report.