Summer Stories: ‘Aatankwadi’

As I listen to my mother talk, I’m glad that I’m running and that the sound of my steps hitting the asphalt, the undulating rhythm of my breathing, can mask the groans and sighs escaping my lips. Her fanaticism, talking about the elections in India and how she voted for Modi, the hard T’s and D’s of her Hindi settling in my ears in a way that English doesn’t, is hard to take. It only makes sense that I vote for a Hindu man in a Hindu country, she says. Who else is going to save us from the terrorists? Again, I am relieved that I am running, that my exasperation is lost in the strain of my breath and gentle beat of my footfalls as I run down the Centennial trail along the river; my mother’s words devour the distant sounds of morning traffic, leaving nothing in my ears except the weight of her disdain for other religions – for Muslims – and the frightening sense of nationalism that has built in her over the years.

Of course, it hasn’t always been like this. This blind faith in a man, in a political party, is something that has been curated in her over the past few years, gulping down tidbits of propaganda every day, swallowing the echoes of hatred churning in the words of those around her, friends and family on her phone, on her daily visits to the local temple, on the TV and in newspapers – everywhere. It is hard for her to see the problem, let alone acknowledge that there is a problem when she is so close to it. At some point, she finally starts to slow down, her words no longer rushing together with emotion, they crawl into my ears more gently now, calmer, and I know that she is about to ask me what she always does.

“When are you coming back?”

I let these words hang as I slow my pace through Riverfront Park, allowing the inertia of my body, my legs, my feet to carry me to the bridge, past the rows of locks embedded in the metal of the fence, to the center where it hangs above the vast expanse of swirling water, right before it drops into the falls farther west.

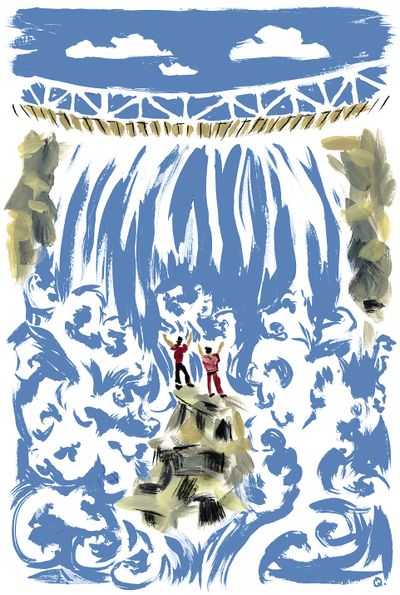

White froth weaves between the clear blue of the water in paisley patterns beneath me, curling and curving and cascading in a way that holds my gaze. The crashing course of its movement fills the silence that has settled on the line, giving me the glimpse of courage that I wish I had – the courage to say I don’t want to go back to Delhi, where my parents have become strangers over the years we’ve spent apart; where politicians have gone so far that there is no avenue for peace; where malcontent and communal violence has turned the city I once loved to a place I am happier loving from a distance. But instead, I simply say soon, and my mother accepts the lie with the same ease that she accepts all the other lies I know her dear leader has been feeding her these past few years. In the end, she mutters a quick goodnight, forgetting that her time is ahead of mine, her Friday coming to a close when mine has only begun.

Here, above the river, I can pretend her problems are not my problems because I am too far away; I can pretend, too, the problems of my friends here are not mine either – their leaders, their government, their petty hatreds and beliefs – because I am still a visitor in this country, an outsider despite all the years that have passed.

Today, the river is telling me to remember. As I watch the water twist and tumble against the rocks below me, I think back to decades ago when my parents and I still lived together, when I was barely 8 and our family was on a trip to Multnomah Falls with another family – my best friend Hina’s family. Hina and I had never chosen to be best friends, but we were the only two brown girls in our kindergarten and had ended up herded together – others calling us sisters, because we had the same black hair cut bluntly at the shoulders, the same tan-brown skin, the same eyes with irises indiscernible from the black of our pupils.

Together, our families had hiked to the top of the waterfall – Hina’s two brothers racing ahead of us, and the cluster of our parents following behind – and I wondered how the rest of our classmates had concluded that we were the same when our eyes were drawn to such different aspects of the world around us – I pointed out the moss on the trees, shuddering at the tiny spiders that spilled from the rich green patches; she rested her hands on the grooved bark of each cedar, looking back at our progress to admire the height we had gained in our journey.

In my memories, that day is highlighted by two events – her older brother racing us to the bottom, zigzagging down the trail, frightening climbers on their way up, frightening us when his momentum kept him going too close to the edge of the trail at each turn. And another event that’s hazy enough in my memory to wonder if I am misremembering: the four of us kids playing in a pool of near-stagnant water at the top – so incongruous considering the violence of the same water’s descent farther on – our wild laughter interrupted only occasionally by the conversations between our parents nearby as they stood watching, until suddenly something heavy collided with my head, leaving behind a ringing sound and throbbing pain through my scalp. For those watching – our parents – it must have been clearer. Her younger brother had been playing with rocks and somehow threw one straight at my head.

Later, in the car, I peered absently at the empty spot beside me in the back – the spot where Hina had sat when we drove to the falls from Olympia. My parents’ adult conversation drifted toward me from the front, their words rushed and exasperated.

“Playing with rocks? That was the first rock he had picked up.” My mother’s voice was high with emotion, quivering with a feeling I couldn’t name.

“You should have known this would happen, you encouraged this friendship with the Pakistanis,” my father said.

“Me? Her father is your friend more than that woman is mine.”

“You’re the one who spends more time with the kids – I told you it was a bad idea.” This time, I could feel the annoyance in my father’s voice, signaling that this wasn’t the first time they had had this conversation. I recalled the way my father celebrated when he watched cricket matches between India and Pakistan on his phone, how he spoke of the wars along their shared border, how Gandhi had ruined everything by proposing the partition but not encouraging all the Muslims to go to the other side.

“The girl is OK. It’s that little brother of hers – that aatankwadi.”

Back then I had no idea what aatankwadi meant – my Hindi, my mother tongue, was sparse, having already moved to a small space in the back of my throat. But now standing on the bridge, as I remember that day, I wonder if that is where it all began. With my mother calling a little boy a terrorist, separating me from the only friend I didn’t feel like an outsider with here in the U.S., all because of imaginary ancestral differences; because Hina was from a different country and worshiped different gods. I wonder if the propaganda that my mother now regurgitated in her words and texts and emails was something that had settled in her heart long ago, its foundation built on that tiny hike up the waterfall, that single event, single accident, single swing of the arm from a 3-year-old boy.

A few moments pass before I finally shake my head and take one last glance at the water churning over dark rocks below. I can feel its vibration underfoot, smell the spray even from this high up, the surge of water that comes with the waning winter. I turn and head back down the bridge, my feet picking up speed as I begin to run; I wonder if I will give my mother a different answer tomorrow, or the day after, or whether I will let the sound of a waterfall always mask what I am too afraid to say.