Old books can be loaded with poison. Some collectors love the thrill.

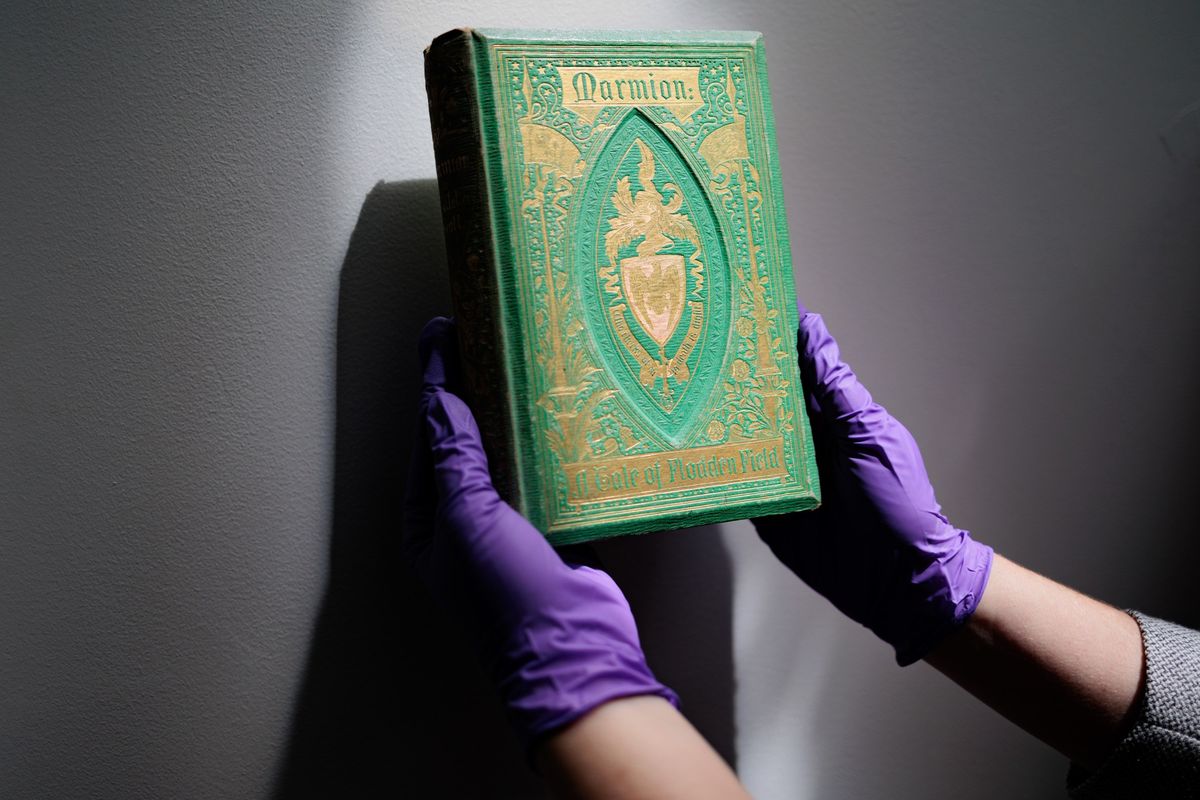

Book binding from the 19th century on a book shelf in Edgar Shannon Library on the Grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, on July 11. (Cal Cary/For the Washington Post)

As a graduate student in Laramie, Wyoming, in the 1990s, Sarah Mentock spent many weekends hunting for bargains at neighborhood yard sales. On one of those weekends, she spotted “The Lord of the Isles,” a narrative poem set in 14th century Scotland. Brilliant green with a flowery red and blue design, the clothbound cover of the book – written by “Ivanhoe” author Walter Scott and published in 1815 – intrigued Mentock more than the story.

“It was just so beautiful,” she said. “I had to have it.”

For the next 30 years, “The Lord of the Isles” occupied a conspicuous place on Mentock’s bookshelf, the vivid green sliver of its spine adding a shock of color to her home. Sometimes she’d handle the old book when she dusted or repainted, but mostly she didn’t think too much about it.

Until, that is, she stumbled upon a news article in 2022 about the University of Delaware’s Poison Book Project, which aimed to identify books still in circulation that had been produced using toxic pigments common in Victorian bookbinding. Those include lead, chromium, mercury – and especially arsenic, often used in books with dazzling green covers.

“Huh,” Mentock thought, staring at a photo of one of the toxic green books in the article. “I have a book like that.”

Mentock shipped the book – tripled-wrapped in plastic – to Delaware. It wasn’t long before she heard back. The red contained mercury; the blue contained lead. And the green cover that captivated Mentock all those years ago? Full of arsenic.

“Congratulations,” the email she received said, “you have the dubious honor of sending us the most toxic book yet.”

The perils of Victorian book publishing

The Poison Book Project began after Melissa Tedone’s own chance encounter with a curious emerald tome.

At the time, Tedone was the head of the library conservation lab at Winterthur, a historical estate and museum affiliated with the University of Delaware, where she assessed and restored objects in the institution’s collection. In 2019, for an exhibition on Victorian aquariums, she was tasked with repairing a book called “Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste.” “It was a bright green book, and the covers had fallen off,” Tedone said. It was her job to put them back on, but she noticed something strange while working.

“There was something about the way the pigment was behaving. I could see it flaking off under the microscope,” she said. At the time, she was reading a book about arsenical wallpaper common in the 19th century. “It was a serendipity moment. I thought that maybe we should test this pigment and make sure it’s not full of arsenic.”

It turned out the book was full of arsenic. “Really quite a lot of arsenic,” she said.

Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele developed the first arsenic green pigment in 1775. The clarity and durability of Scheele’s green made it wildly popular.

“Imagine you’re in 19th century London, the heart of the industrial revolution. It’s sooty, grimy, everything coated in gray. People missed this fantasy of nature,” Tedone said. “This green pigment was the first that stayed bright green. There really wasn’t anything like it.”

Soon, arsenical greens were everywhere. “Women were wearing these ball gowns full of arsenic pigment, which shed arsenic dust as they were whirling around on the dance floor,” Tedone said. People understood that arsenic could be dangerous, but until chemists came up with safe, synthetic green dyes in the early 20th century, “it was kind of a free-for-all.”

Tedone and other conservators have long been aware of the possibility of arsenic in Victorian clothing and textiles, but the idea that the toxic substance might be found in book cloth from the era “had sort of fallen out of the historical knowledge,” she said.

Because “Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste” was mass-produced, Tedone knew it couldn’t be the only book in the world that contained arsenic – and perhaps other toxic heavy metals – in its book cloth. She and her colleague Rosie Grayburn started the Poison Book Project to investigate how many of these toxic books are still around.

For the past five years, they’ve been encouraging colleagues at universities and libraries around the world to look through their holdings for poison books, while visiting smaller institutions that lack the equipment to run the tests.

Curators use a method called X-ray fluorescence to investigate the chemical makeup of book covers. “It’s a device that looks like a ray gun tethered to a computer,” Tedone said. “Basically, you point the ray gun at the object, and pretty quickly the computer tells you what’s in it.”

About 50% of the books that have been analyzed have tested positive for lead, which is present in multiple pigments as well as pigment enhancers. Chromium has shown up in Victorian yellows, and mercury in the era’s intense reds. Arsenic, the most toxic of these chemicals, has been found in 300 books, including those with benign titles such as “The Grammar School Boys” and “Friendship’s Golden Altar.”

“Arsenic is in its own category,” Tedone said. “Not only is it more toxic than the other heavy metal pigments, but we are finding that measurable levels of arsenic are coming off on your hands.”

The findings have led large institutions, including the National Library of France and the University of Southern Denmark, to remove books from circulation and place them in quarantine.

A curiosity for collectors

Not everyone is unhappy to find a poison book in their collection, though.

Todd Pattison, a Boston book conservator, said that during his 30 years of collecting, when he came across one of those “fairly rare books with that particular green color, I bought it strictly for that cover. Because it was so unusual.”

Thanks to the Poison Book Project, he found out in 2019 that the rare books he was so drawn to contained arsenic. “I look at them very differently than I did before,” said Pattison, who knew about heavy metal pigments in wallpaper and illustrations “but didn’t really think outside the box” when it came to book cloth.

Pattison, who teaches courses at the Rare Book School on 19th century American book bindings, still uses the books in his classes. “We look at them differently and take special care, but it’s a great reminder we still have so much to learn about these cultural artifacts.”

Some book lovers will settle for just a glimpse of one. When Brooklyn booksellers Honey & Wax offered up a lot of nine arsenical books at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair in April, “lots of people just wanted a selfie with the books,” owner Heather O’Donnell wrote in an email.

Staff had discovered the books in a recently consigned collection of 19th century volumes “and thought that marketing the poison books as such might be an effective way to raise awareness of bibliotoxicology,” O’Donnell said, “and get the books out the door swiftly.”

The marketing paid off. All the arsenical books – which ranged in price from $150 to $450 – sold within 48 hours.

“We sold most of the books to private collectors. No one we met was working on a dedicated arsenical collection,” O’Donnell said. “Collectors mostly wanted one nice example of the category as a curiosity.”

‘Don’t lick your green book’

Think there may be a poison book on your shelf? Don’t panic, Tedone said.

“They’re a really interesting and important part of material culture and our history. It’s just a matter of knowing what you have and handling it safely.”

If you suspect you have a toxic book, you can look for its title in the Poison Book Project’s database, which is updated frequently. The project will also mail you a free bookmark with color swatches for a visual (but less accurate) verification.

According to Tedone, books with heavy metal pigments should be stored in a plastic bag to contain any shedding pigment. “It doesn’t have to be fancy; a gallon-sized bag from your grocery store will do.”

If you still want to read the book, do so on a hard surface and wear nitrile gloves, which are available at any hardware store and provide a bit more protection than average latex ones.

When you’re done with the book, put it back in the bag, wash your hands and wipe down the table.

“You probably have more dangerous things under the kitchen sink,” Tedone said. “You wouldn’t drink tile cleaner; don’t lick your green book.”

Back in Wyoming, self-proclaimed “inveterate yard-saler” Mentock, who happily donated her very poison book to the Poison Book Project, admits she wouldn’t mind reintroducing a little danger to her collection.

“We’re building a floor-to-ceiling library, so I still keep an eye out at yard sales,” she said. “I haven’t seen one yet, but I’m on the hunt.”