‘He was a force of nature’: Tracy Walters, legendary Rogers cross country coach, dies at 93

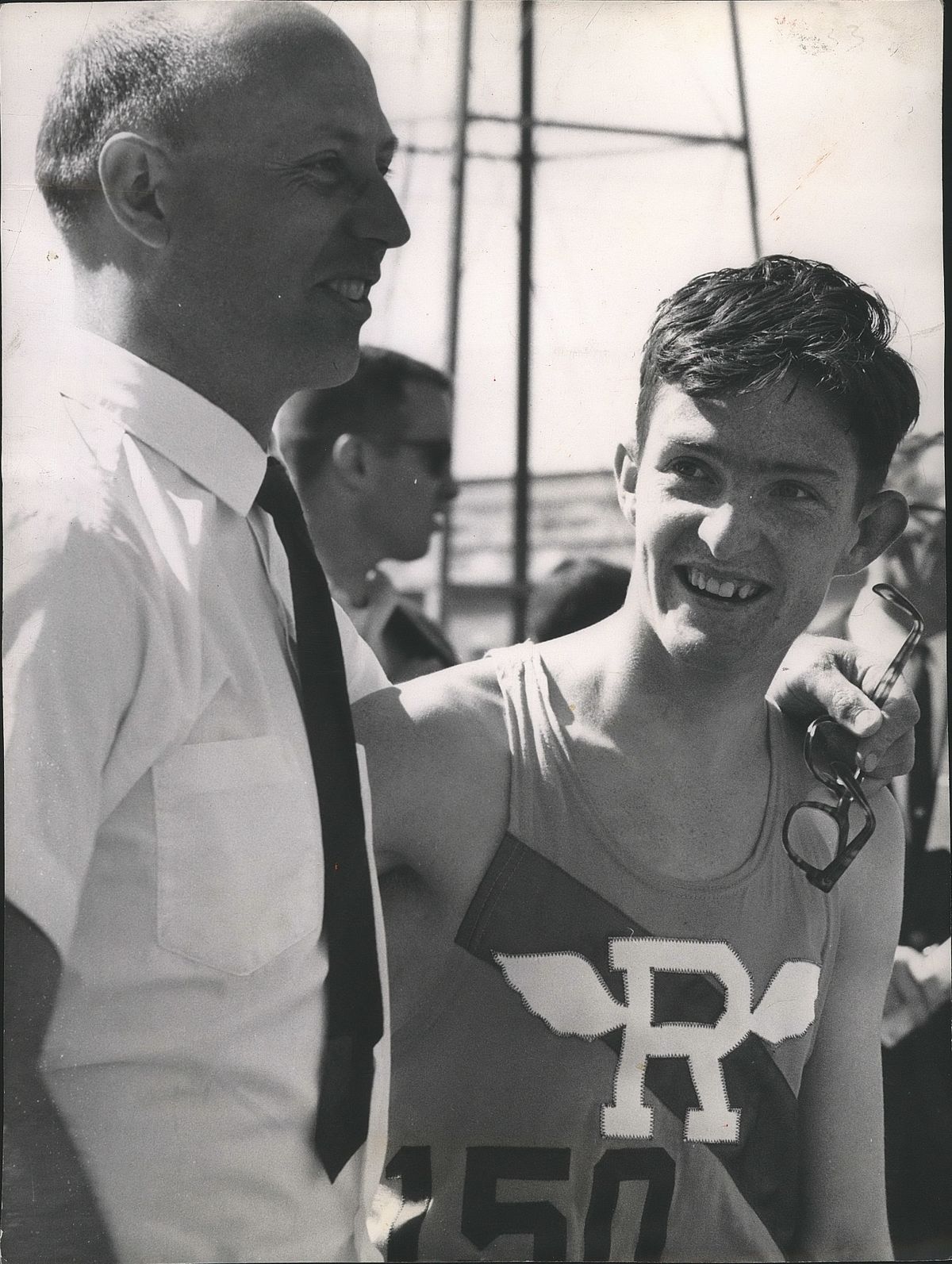

During A legend’s Homecoming Rogers track reunion, runners, left to right, Len Long, Gerry Lindgren, Steve Jones and their high school coach Tracy Walters talk about Lindgren’s accomplishments, including his 10,000 meter win against the Soviets in 1964, Wed. May 29, 2024, at Rogers High School. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

Coaching a teenage Gerry Lindgren to national records and a Cold War conquest of the Soviet Union’s veteran distance runners wasn’t the least of Tracy Walters’ legacy.

But given his reach in Spokane, it can almost seem like a footnote.

Coach, counselor, fruit baron, summer camp steward, motivator and pied piper, Walters was all of these and more in a remarkable life that came to a peaceful end Saturday at the age of 93.

“He was a force of nature,” said Bloomsday founder Don Kardong, who sought Walters’ counsel when he was training for the 1976 Olympics. “He had a charisma that was irresistible, and he encouraged and motivated so many people.”

And it went well beyond a quarter-mile track or a cross country meet – but that’s where it started and carried on into his 80s.

At Rogers High School, he established a dominant cross country program beginning in the late 1950s that won 48 of 52 dual meets over the course of 10 years and claimed state championships in 1963 and 1965 – the first led by the astounding Lindgren, but the second every bit as strong with four runners placing among the top 10.

Lindgren’s rise to national renown and the Olympics spread Walters’ reputation, too; he was twice named to U.S. national team coaching staffs. But in reality, Walters’ gift was an ability to reach the average athlete – and in volume.

“For that era, we had an unheard number of kids – 50 to 60 – out for cross country,” said Steve Jones, who not only ran for Walters but lived with his family as a senior after his parents moved to Vashon Island, Washington. “We had kids that would never come close to a varsity spot but were there because they wanted to be part of a positive program. Dan McMackin was a fabulous sprinter and he even turned out because Tracy convinced him it would help him on the track.”

It didn’t have to be over the top. In a recent return to Spokane, Lindgren recalled a particularly “lousy” workout his first year that ended with Walters throwing an arm around his shoulder and saying, “If you keep at this, you’ll be one of the best in the school.”

And Jones noted that his coach wasn’t above some appealing gamesmanship.

“Our main rival was Ferris, which had Rick Riley, of course,” he said. “The week of our meet with them, he had us run from Rogers all the way to Ferris, up Freya hill, and do a mile loop on their course in front of their guys. He’s holding a stopwatch and yelling out our times – and I swear he improved them by 10 or 15 seconds. Then he yells out that we’re going to run all the way back – except we ran a couple of blocks and he picked us up in his car.

“That was pure Tracy and we loved it.”

Walters’ enthusiasm didn’t flag with age, either. At age 68, he was hired as an assistant coach by his son when Kelly Walters took over the track program at North Central – and discovered new facets to his father.

“First, he was never too proud to learn from other people,” Kelly Walters said. “We assigned him to coach pole vaulters and he got with (former Ferris coach) Herm Caviness and learned all he could. We had him work with hurdlers and though he’d done that successfully decades before, he got with Linda Lanker and learned more.

“And he simply delighted in every kid. He might have somebody who had never hurdled before and the first time the kid managed to pull his trail leg through properly, his voice would boom through the stadium, ‘Kelly, you’ve got to come look at this!’ It was if he’d won the Olympics. Kids knew they were loved and valued.”

That was perhaps even more evident during the four years he served as director of Camp Reed, the YMCA institution on Fan Lake.

Walters had left Rogers in 1966 to become cross country coach at San Jose State, where he took the Spartans to a third-place finish in the NCAA championships. But disenchanted with California life, he returned to Spokane as a school counselor just a year later. In 1968, he was approached to take over Camp Reed, which Kelly Walters said was languishing and “bleeding money” to the point that the YMCA was considering selling the property.

By the end of the first summer, Walters had the weekly sessions full. His athletes were hired as counselors – and everyone got a nickname. Kardong, lured by his Stanford teammate Jones, was “Dingy.” Lee Evans, the sprint great at San Jose State, did a week at Reed before winning the Olympic 400 meters two months later in Mexico City. Kelly Walters and sister Malinda met their future spouses working there. Counselors returned as directors for the next 20 years.

“It was more than just a summer job for us, and for him it was a chance to build a culture,” Kelly said. “He told us to look for the kids who weren’t involved or homesick and make them a part of things. And we’d get excited about everything – you might get assigned to lead the Lost Lake Hike, which was a pathetic little hike to a lake that wasn’t lost, but you’d make the kids feel they were on a big adventure.”

But the greatest adventure was yet to come – Walters Fruit Ranch.

Walters was closing in on retirement from the school district when he and his wife Leta bought a lagging orchard on Green Bluff in 1975. Over time, 2,000 trees were planted in a crop makeover, a building was added to serve food, reporters were alerted to “the most amazing cherries ever” and apples that had once been sold to Tree Top and shipped back to Spokane stores became the center of a U-pick destination.

And leading the tours for preschoolers was “Farmer Walters,” buzzing around like a bee pollinating the apples and making like a deer helping himself to a snack.

“What cracked me up is that he’d invite people up from retirement homes,” Malinda remembered, “and he’d do the same routine – except he’d say, ‘This is what I say to the little kids,’ and then they’d get to enjoy the story and not feel like they were being talked down to.”

The Walterses sold the ranch 25 years ago, and Leta died in 2022 after 71 years of marriage. A son, Marc, predeceased them. Tracy Walters is survived by sons Scott and Kelly and daughter Malinda, and 12 grandchildren.

And by countless runners who may not even know his legacy.

“There was probably a distance running tradition before Tracy,” said Kardong – and, yes, both Shadle Park under Jim Berry and Lewis and Clark under Art Frey won state championships before Rogers. “But he took it into the big time. There have been some great coaches, athletes and teams since, but it all seems to go back to Tracy and the people he coached and inspired. His influence just goes on and on.”