State superintendent challenged by three opponents in race to oversee public education

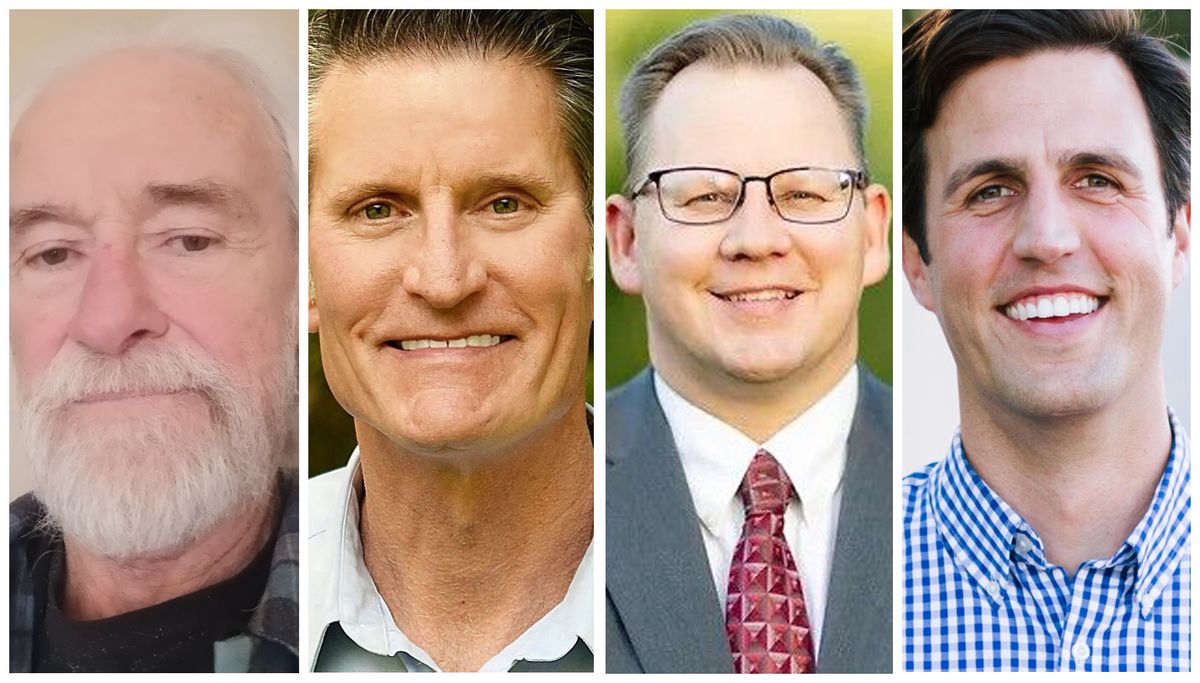

Candidates for superintendent of public instruction in Washington’s Aug. 6, 2024, primary are, from left, John Patterson Blair, David Olson, incumbent Chris Reykdal and Reid Saaris.

Three challengers seek to head public education in Washington, vying for the role of superintendent of public instruction held by incumbent Chris Reykdal since 2017.

The elected state superintendent position pays around $166,000 yearly and the term lasts four years. It is a nonpartisan position.

Reykdal has served two terms, tasked with overseeing state public school budgets and K-12 educational policies at the Legislative level. He’s proud to have made strides in early learning, free meal access and graduation rates that he hopes will spur voters to select him for a third term.

Reykdal said his eight years as superintendent of public instruction, time as a state Legislator, a school board member and teacher give him a nuanced perspective with which to guide public education, or “the greatest tool of democracy we’ve ever created,” as he called it.

“We grow this idea that together every child has this democratic opportunity to accelerate,” Reykdal said. “We invest even more if you’re high poverty, if you have a disability, if you have a nutritional need, so we also lean into the progressive idea that some students need a little bit more, but doing it together is what makes it public.”

Reykdal isn’t the only name on the ballot with experience; each of his challengers also work in public education roles. Challenger Reid Saaris is a former teacher, substitute and founder of nonprofit Equal Opportunity Schools that consults with districts on how to bridge “opportunity gaps” and ensure challenging classwork is available for kids of all backgrounds, he said.

He seeks to apply his 10 years leading his nonprofit in advancing equity to leading state education, coordinating with schools who’ve seen success in different areas, like college or career readiness to mirror the successes across the state.

“We’re not doing a great job of matching people with careers or post secondary opportunities, and there’s places within the states that are very successful with this work, but it’s just not systemic,” he said. “That’s back to my core motivation in my whole career, how do we make these things work consistently for kids from all backgrounds and all parts of the state?”

State Republican party-endorsed candidate David Olson has sat on the board of the Peninsula School District in Gig Harbor for more than a decade. He said he’s seen students perform poorly over time in areas like math, reading and science. Under Reykdal’s leadership, he said school districts have lost much of their local control through state-level mandates.

“The current superintendent over the past five or six years has not been super friendly to school boards,” Olson said. “He’s sort of telling us, ‘It’s my way or the highway, if you don’t do this, I’m gonna take your state funding.’ ”

Libertarian-leaning candidate John Patterson Blair’s experience lies in teaching, curriculum development and four years on the Vashon Island School Board. It’s also his fifth run for the state superintendent position, but not because he wants the job, he said.

“In fact, as I jokingly have told friends, the first thing I would do if I won was demand a recount,” he said. “My goal is to just put out an idea and so people are aware of it.”

Blair’s campaign is based entirely around his proposed “new foundation” in the schooling system where each student receives a trust account with the amount the state would pay for their education based on their apportionment in state’s funding model. Last year, the state paid an average $18,000 per pupil, with different allocations if a student was in special education or low income, for example.

Their parents could then use this trust to pay tuition at a registered school of their choice, allowing for more freedom in their child’s schooling, whether it be home-school, a project-based alternative school or a public school.

“There’s a real advantage to studying on your own,” Blair said. “Say you want to do violin, you hire a violin teacher for an hour or two a week at 200 bucks an hour, and you’re getting really great training. The idea is to give individuals control and they aren’t penalized for failure.”

His plan also includes districts with locally elected advisers to oversee progress of students in their neighborhoods and one to maintain facilities.

Here’s where each of the candidates stand on other issues facing education.

On state funding

Education consistently receives the largest apportionment from the state budget, with around 1.1 million students enrolled in Washington public schools. Candidates differed on how they would urge lawmakers to direct these funds.

All six bonds on August ballots failed in Spokane County last year; some regional levies also failed. Freeman’s capital levy, intended to pay for construction and technology, failed twice, in August and February. Moses Lake School District’s educational programs and operations levy failed twice, resulting in upcoming staffing reductions and extracurricular cuts.

Olson said the state fails to fund public education sufficiently, eyeing transportation needs and “unfair” models that put too much burden on local property taxes to fund schools through levies and bonds. Taxpayers in rural districts with less property value than larger districts, like Seattle, end up having to pay more toward their schools, he said. As such, these districts struggle to pass levies and bonds. Levies are used to pay for student needs beyond basic education and bonds for school construction needs.

“I want to make sure that we’re being fair and that school districts that are having a tough time passing their levies and bonds, what can we do to help them?” he said.

If elected, he said he’d solicit advice from a team of financial experts and completely reimagine funding formulas and urge the Legislature to implement his findings.

Bonds, which authorize districts to borrow money to pay for major construction, require 60% voter support to pass, while levies need a simple majority.

Reykdal said he supports a bond threshold reduction to a simple majority and would continue advocating to lower the “undemocratic” threshold.

Reykdal said the state’s funding formula hasn’t kept up with inflation and estimates schools need an additional $1 billion, at least. He advocates for funding adjustments in formulas that fund transportation, school construction and special education. While state allocations for special education have increased during his terms, he said many school districts are supplementing special education through levy taxes, contrary to the state’s obligation to fund basic education. He estimates an additional $400-$500 million in special education investments are needed.

“The places we have to really double down on are all those wrap-around supports for kids,” Reykdal said. “Things that aren’t necessarily obviously in the classroom, but they really make for successful students: mental health, physical safety, nutrition.”

Mental health improvement is a priority in Saaris’ campaign, he cited declining mental health in youths and plans to address the state comprehensively with universal access to mental healthcare for students.

“We had a mental health crisis and it was declared a state of emergency, the mental health of adolescents and we are having real challenges around academics. So to me, the opportunity for leadership at OSPI is to really be that thought partner with folks.”

Saaris said there are gaps in Washington’s education funding formula that create disparities between high poverty districts and their more affluent counterparts. He looked to other states that have revamped funding formulas and proposed funneling 30% more resources into schools with more low-income students.

Blair’s proposal provides for parents’ independence in how their apportionment is spent, but doesn’t alter the formula that allots more dollars to some students, like those in special education or low income.

Chronic absenteeism

The rate of regular attendance has plummeted across the nation emerging from pandemic-era school closures. A chronically absent student is one who missed at least 10% of the school year for any reason, averaging out to two days absent per month.

In Washington, the proportion of chronically absent students doubled from 15% to 30% between the 2018-19 school year, the last full one before the pandemic, and 2022-23, the latest year with available data.

Students suffer academically when they miss class, Olson said, especially in advanced math classes. His school district is above the state average in regular attendance by about 7%, to which he credits schools engaging parents to determine the underlying causes of absent students, perhaps illness or social or academic stressors. He’d advise districts to start with similar inquiries with families.

“I’d like to know, working with parents as much as they’re able to work with the school district, to find out what’s the cause of the absentee kid and try and get them to be back in school,” he said.

Blair similarly advocated for starting by asking students why they miss school. He reasoned many families are removing students from school in favor of homeschooling.

To bring kids back to the classroom, Saaris proposed enticing them with engaging schoolwork and opportunities for connection to school. He referenced phones and social media contributing to disengagement. Teachers fight an uphill battle for their students’ attention against tech giants whose algorithms are designed to distract, he said.

If elected, Saaris said he would partner with the governor and state attorney general and the trio of office newbies could collaborate to restrict social media use for kids, enforcing age minimums for using social media.

“Part of it is probably related to the purview of the attorney general and others to say, ‘You know, we really need to hold companies responsible for following the law on these things,’ ” Saaris said. “Then schools can support parents and students in awareness and age verification in ways that are privacy protected,” he said.

Reykdal said attendance has been improving post-pandemic, crediting school districts that intervene early when they notice early attendance patterns. He said parents are increasingly excusing their students for illness-related reasons, something he expects to persist especially as new COVID variants develop.

“As long as we have a virus that’s knocking people out, you’re gonna see slightly elevated absences compared to pre-pandemic, but it is improving,” he said.

Sex education

Reykdal and Saaris said they supported the current system surrounding sex education that provides districts to select their own curriculum as long as it’s in line with state policy and OSPI learning standards.

Olson said he’d advocate for an “opt-in” approach to sex education where parents deliberately select the class for their student, rather than the current approach that allows parents to opt their child out. The opt-out option applies to any curriculum.

Parents can easily miss opt-out notifications, he said. A change in model would prevent a situation in which a student receives a lesson their parent disapproves of.

“They’re busy and they come home, maybe they missed the email from the school district or the backpack note or whatever that says their kid’s going to have a curriculum and they miss the opportunity to opt out,” Olson said.

While he’s not sure exactly how it would work, Blair idealized a more personalized approach to sex education where parents could select from different curriculum options for their child.

“This is a libertarian idea that the individual family should have this say of what goes on with their kid,” Blair said.

Saaris, who has racked up the most campaign contributions and spent the most, is endorsed by the Seattle Times and Mike Wiser, Spokane Public School board member, according to his campaign website.

Incumbent Reykdal has the endorsements of the state teacher’s union, the Washington Education Association; and Spokane County Democrats. Spokane-area Legislators Marcus Riccelli, Andy Billig and Timm Ormsby support Reykdal, according to his website.

The state Republican Party endorsed Olson, as did Central Valley School School Board members Pam Orebaugh and Anniece Barker and Mead School Board members Jennifer Killman and Michael Cannon, according to his website.