Broken Records: Citizens face growing obstacles to public records – and legislators are making them worse

Spokane City Councilmman Michael Cathcart is proposing the passage of a new ordinance to require putting already completed records requests online. (Daniel Walters/InvestigateWest)

Emily Moyer, a 37-year-old photographer, was hoping public records could help save her fiance.

With his criminal history and an arrest for drug and firearm possession charges, she said, he was facing life in prison. His public defender was overwhelmed.

So on April 12 of last year, Moyer asked for the disciplinary records for a slew of Spokane police officers involved with her fiance’s case.

Speed was crucial: The trial was in August.

Moyer was using one of the most important tools the public has for holding government agencies accountable. Ever since voters passed the Washington Public Records Act initiative in 1972, everybody – no matter who they are – can obtain copies of most documents produced by state and local public agencies.

Think of it as a legal crowbar that anyone can use to crack open the government’s closed doors, revealing the secrets inside.

When Moyer got the first records back, they showed multiple officers with a history of discipline problems. Officer Darrell Quarles, to name one, had been written up for repeatedly failing to activate his body camera, making an illegal traffic stop and associating with a drug-dealing prostitute. The records could have “raised credibility questions as far as Officer Quarles testifying,” Moyer said.

But by then it was Sept. 29. The trial had been over for nearly a month. Quarles had testified, and her fiance had already been sentenced to 16 years in prison.

She’s still waiting on the rest of the records.

“It really does me no good now,” Moyer said. “I just thought it was weird that they waited that long.”

But in Spokane, at least, it isn’t weird for records requests to take that long: It’s frustratingly common.

Roughly 100 records requests to the city of Spokane from November 2022 through November 2023 took six months or longer to fulfill, according to the city’s records log. In fact, a request to obtain just a list of requests took over four months.

When InvestigateWest brought the problem to Spokane’s leadership, recently elected Mayor Lisa Brown committed to hiring new staff and a council member proposed passing new legislation to try to fix it.

But the problem isn’t just in Spokane.

“Delays are terrible,” said David Cuillier, director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida, which advocates for public records access. “They’re getting worse.”

A rising flood of records requests – driven by partisan tensions, technological innovation, corporate data-mining, and “vexatious requestors” bombarding governments – have increasingly swamped under-resourced records agencies. Across the Northwest and the country, citizens are facing longer wait times, steep fees and other obstacles to obtaining government records the law says they deserve. It’s happening at the federal level, too, with average wait times doubling in the past decade, Cuillier said.

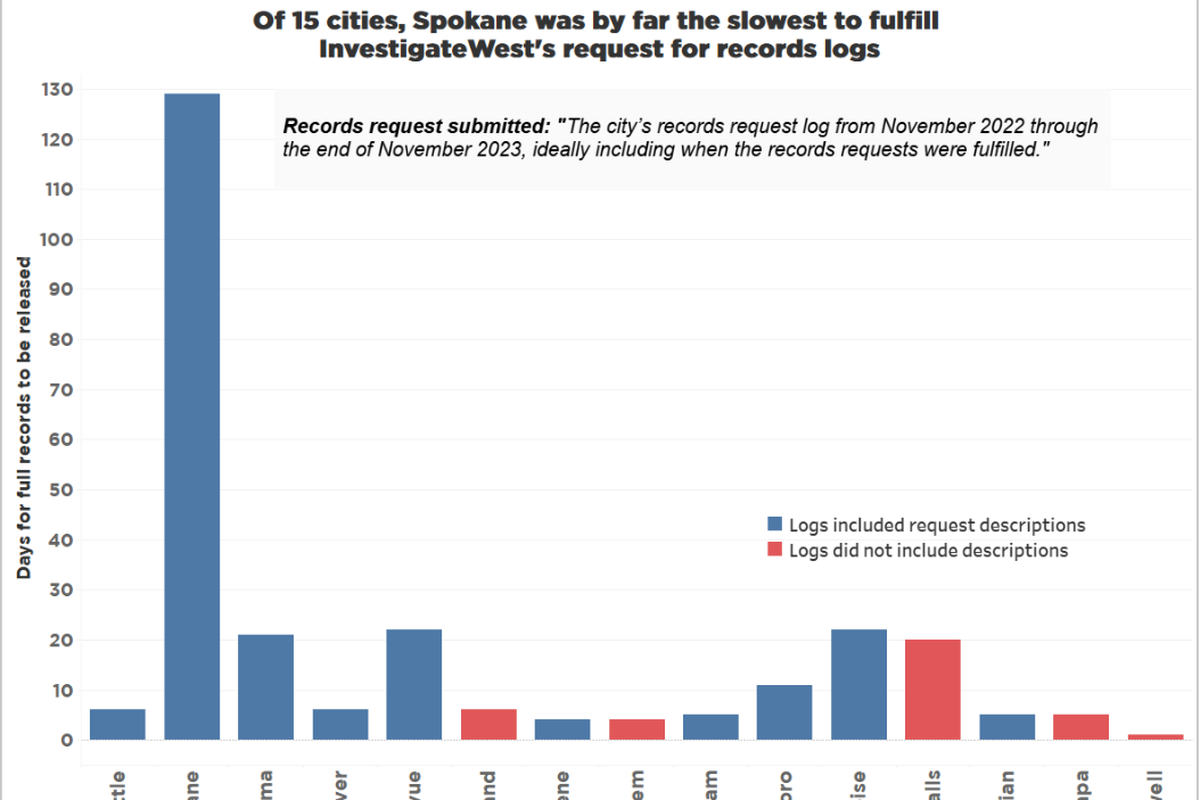

The sense that public records responses throughout the region were slowing to a crawl sparked an experiment by InvestigateWest: To assess the speed, thoroughness and cost of local public records systems, we gave the same two record requests to 15 cities in the Pacific Northwest.

The results varied dramatically, but highlighted the seriousness of two major barriers: In Washington’s largest cities, the delays for some types of records could stretch out months, while the records fees in Oregon and Idaho could run into the hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars.

As requests keep flooding in, records advocates fear that legislators in all three states will respond by further damming up access to public information – raising fees and passing more laws limiting the availability of public records. And in Washington, in particular, transparency advocates and records clerks say, such rules have made the delays much worse.

“It’s a shame,” Cuillier said, “because in our research, Washington state was one of the best states in the country when it comes to access to government information.”

The test

Last December, InvestigateWest asked the five biggest cities in Washington, Oregon and Idaho for their log of records requests from November 2022 through November 2023. We also asked each city for a week’s worth of communications involving either the mayor or the city administrator or managers.

Vancouver, Washington, was the clear winner, completing both requests – including over 1,800 pages worth of emails and texts – within just eight days. And unlike Portland, which asked InvestigateWest to pay $1,800 for communications involving the city’s mayor or chief of staff, Vancouver didn’t charge a dime.

Washington’s two largest cities struggled: Spokane was by far the slowest, taking 129 days to provide records logs, nearly six times slower than any other city tested. InvestigateWest has been waiting more than seven months for Spokane to release all the requested messages from the mayor and city administrator. Seattle, meanwhile, took 42 days to deliver an installment of just nine messages from the mayor and the chief operating officer.

Portland’s and Spokane’s records departments objected to InvestigateWest’s test, arguing that it was like comparing “apples and oranges,” considering the wide variety in city sizes, staffing levels and varying job titles.

The test had a slew of limitations: Spokane’s records log, for example, was far more detailed than Caldwell, Idaho’s or Portland’s. A few cities, like Portland and Seattle, didn’t have any “city administrator” or “city manager,” forcing us to pick another high-level official. Some cities mistakenly provided only messages between the two officials, instead of all messages that included either.

But InvestigateWest’s test is just one data point in a constellation of evidence pointing to the same problems. Data submitted to the Washington Legislature show that Spokane took a full month of business days to complete a records request on average in 2022 – three times longer than the average city in the state. Seattle took almost twice as long as Spokane.

Individual examples abound. When Nate Sanford, a reporter at the Inlander, asked the city of Spokane for a copy of its 2022 records log, he was told he would get it within “approximately two weeks.” It took 10 months.

And when Stranger reporter Ashley Nerbovig asked the Seattle Police Department for a single document on June 3, she was told she would have it by the 28th – of February 2025.

“A woman can produce a baby in about as long as it takes SPD to produce a single police report,” she wrote on social media.

Laws in the three states differ on how quickly officials must fulfill requests. Idaho’s law requires providing most records within 10 business days. Oregon’s encourages completing a response within 15 days, although it lets cities slide if, say, they don’t have enough staffing. Washington law requires governmental agencies to provide the “fullest assistance to inquirers and the most timely possible action on requests for information,” including providing a “reasonable time estimate” within five days.

“ ‘Reasonable’ ” depends on the record, said attorney Kathy George, who has represented organizations like the Seattle Times in records-related lawsuits. She noted, however, it would be “ridiculous to take five months to produce a single record” like a records log. Plenty of cities throughout the region appear to sometimes violate that standard.

Anyone can sue over unreasonable delays, but many citizens, and media outlets, can’t afford to. And Candice Bock, lobbyist for the Association of Washington Cities, said the possibility of lawsuits can backfire, making public records officers more nervous and less forthcoming.

“When you are worried about ‘Will this result in litigation?’ it slows things down,” Bock said.

The great records glut

Major records delays can result from poor records organization, understaffing or miscommunications, records advocates say. But talk to records officers and they’ll point to one problem in particular: volume.

According to state Legislature data, the average time it took Washington cities to complete records requests increased by 25% from 2018 to 2022. One reason? The number of requests had increased by more than a third.

“Over the last decade, what I hear the most from cities is just they get so many more requests,” Bock said. “And the requests are more complicated.”

Technology was supposed to come to the rescue. Since 2005, Washington’s Local Governments Grant Program has given away millions to help cities and counties upgrade to record management software like GovQA.

That did make the process more efficient, but it also removed the speed bumps in both directions. It was easier to fulfill requests and easier to make them, too.

“These online portals reduced a lot of the friction to making these records requests,” said Tony Dinaro, public records officer for Spokane County, which used the grant program to upgrade to GovQA in 2018. “It made it a lot more visible to people.”

At the same time, Dan Huizinga, product manager for GovQA, said governments kept producing more records, “as public agencies move through the process of digital transformation.”

When police departments started using body cameras, all that video became available to activists, attorneys, and those YouTube channels that turn police footage into videos with titles that include “When a Cannibal Killer Spots His Next Meal” and “Woman Uses Her Teeth to Rip Out Sister’s Eye.”

When COVID hit, officials began holding meetings on Zoom, Microsoft Teams and WebEx, creating new genres of records.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, gosh, we’ve got these chats,’ ” Bock said. “When do you keep them? How do you keep them? Where do you keep them? We keep adding to the pile.”

As distrust in institutions has grown, partisans and skeptics have relied on records requests to do their own research. As election-related conspiracy theories have grown, Dinaro said one Spokane County man recently asked for three weeks of footage from every surveillance camera outside the Spokane election office.

Widely publicized police abuses have ignited a swarm of inquiries into police departments. National fights about COVID restrictions, critical race theory and transgender identities led to an explosion of records requests of schools from conservative groups and parents.

And that can spark backlash against the record process. When Toby Nixon, former president of the Washington Coalition for Open Government, gave his public records presentation to the local chapter of Moms for Liberty, a far-right group activist group, he was accused by one critic of teaching “extremists how to burden local school districts” with “unnecessary records requests” used as a “tool to harass and intimidate.”

The rich get records

Carrie Wilton, legal records supervisor for the city of Portland, marvels at the way that residents in Washington can “ask for the whole world” and there’s little officials can do to curtail them.

By contrast, Oregon and Idaho charge fees for complicated records requests. Ultimately, Wilton argues, that is an advantage for everybody. Records officers can use fees to try to push requesters to narrow broad requests, and provide records more quickly.

In 2017, Washington passed legislation to allow some agencies to begin to use limited fees as an attempt to deter “vexatious requesters” – those who ask for unreasonably large batches of records, particularly those with malicious intent.

But typically, fees in Washington pale in comparison to neighboring states.

One analysis of tens of thousands of records requests made through MuckRock, a records assistance website, found that their Idaho requesters faced the steepest fees in the country, while fees have remained the lowest in Washington.

Reporters from Portland describe the fee negotiation process as a constant source of frustration, a haggling ritual that becomes a battle of wills.

Worst of all, since Oregon charges for the actual wages involved with the work performed, the more inefficient an agency is, the higher the penalty.

“I once had a small city east of here that had 17 different people review a request and each one of them charged by the hour,” said Therese Bottomly, editor of the Oregonian.

A 2023 study co-authored by Cuillier argued that “aggressive pursuit of fees merely adds another task to already overburdened agency staff” while serving as a barrier for those that “cannot pay, namely, regular citizens, journalists, and scholarly researchers.”

In theory, records staffers in Oregon and Idaho can waive fees if the records are in the public interest. But that can be wildly inconsistent.

InvestigateWest requested a fee waiver for a week of communications involving either the Portland mayor or his chief of staff. The estimated $1,800 bill worked out to roughly $63 an hour, or an estimated $9 for every 10 messages. Portland offered to provide one hour of free work, but wouldn’t budge on the overall price unless we narrowed our request.

Of the nine other cities InvestigateWest sent similar records requests to in Oregon and Idaho, only one – Hillsboro, Oregon – was willing to fully waive the fees. InvestigateWest didn’t pay the fees, and therefore, was not able to get all the requested records.

In 2022, the Salem Reporter asked for documents relating to the exit of the deputy police chief. Salem initially charged over $4,200 for one set of records. The newspaper raised money from their readers to cover the cost before the city relented. In 2020, the Oregonian had to pay more than $2,000 to get receipts from Douglas County showing that commissioners had wildly misspent federal funds on lavish flights and dinners.

“The clear feeling among practitioners who use the public records law a lot – not just journalists – is that fees are another way to create hurdles to disclosure to make people go away,” Bottomly said.

And if requesters are truly trying to be a nuisance, even Portland-sized fees won’t stop them.

In December 2022, Patrick Cashman, a Portland records activist who previously crusaded against the city’s refusal to reveal the route of the World Naked Bike Ride, asked for every single record the city had released that year to other requesters. It was an attempt, he wrote in an email to InvestigateWest, to push the city to upload all those records to an open data portal like federal agencies do.

Instead, Portland asked him for nearly $68,000 to review and upload the records again. So Cashman hit back: He split up his request into 365 separate pieces, one for each day.

Cashman’s not above paying for records – he shelled out nearly $3,000 for Portland records alone – but Wilton said he didn’t pay the bill on any of those 365. He just made the city jump through a year’s worth of hoops, then abandoned them. To Cashman, it was a “free speech exercise,” a way to protest an unaccountable, “byzantine” records bureaucracy.

“I enjoy torturing city personnel because it really is the only way we citizens can get some payback,” Cashman wrote in an email to InvestigateWest, reasoning he “might as well make every day of their life an unendurable hell until they decide on a different career.”

A report issued this year from Portland’s Legal Records Team dedicated an entire section to Cashman and called for new legislation to stymie this kind of requester.

But records advocates are wary of such proposals. The line between vexatious and merely persistent is thin, and sometimes gadflies and trolls uncover scandals and change policies. Bottomly recalled a woman who’s made numerous records requests about the Multnomah County Animal Shelter over two decades.

“That is somebody who has made it her life’s mission to be a citizen watchdog of the animal shelters,” Bottomly said. “There are citizens who, bless ’em, take very seriously their responsibility to monitor government.”

And even the requests of someone like Cashman are dwarfed by the real giants in the room: data brokers.

In a brief span between 3:50 and 3:55 a.m. on Feb. 7, Justin McNeal made 14 record requests in Portland, part of a spree of 151 requests that day alone.

And last year? McNeal made over 9,000 record requests to Portland – 11 times more than every media request in 2023 combined, almost all for accident reports.

McNeal doesn’t live in Portland. He lives in Atlanta, where he’s an operations manager for LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

LexisNexis is a data broker, a company that makes its fortune hoovering up records on practically everything – criminal history, debtor information – and then selling records and data insights to insurance companies, law enforcement and even back to consumers.

Through LexisNexis, McNeal paid Portland more than $110,000 last year. Meanwhile, a single requester from a competitor, MetroReporting, paid more than $13,000 for more than 1,000 individual records last year.

It was the requests from these sorts of companies that, according to a report from Portland’s Legal Records Team, brought the Portland Police Bureau record system to its knees. At its worst, in January 2022, Portland’s police records had a backlog of over 22,000 open requests and two-thirds of them were taking more than two months to fulfill.

Cuillier, the records expert, said it underscores his study that shows fees don’t do much to deter some of the most high-volume requesters, like attorneys or data brokers.

“These companies, they’re perfectly happy paying to get this data because they make money off it,” he said. “The public interest requesters … they’re ones who are getting hosed.”

650 and counting

In the past decade, there have been reforms to expand records access in Oregon. But Washington and Idaho legislators keep running in the other direction.

In 2020, Idaho legislators passed a bill to exclude legislative notes and the names of private citizens who communicate with them from records requests. And last year, the Olympian reported, Washington state House Democrats figured out a creative way to reinterpret a state constitution provision into a “legislative privilege” that they have used to ignore many records requests.

Some legislators have pointed to the burden on local governments and state agencies as a reason for weakening public records laws. This year, for example, Idaho legislators passed bills doubling the time allowed to fill records requests coming from out of state.

Yet by winnowing public records laws, legislators have often made the delays worse.

The hard part of a clerk’s job isn’t locating records. It’s reading thousands of pages of documents, spotting parts they legally need to redact, like lists of names if a requester wants them for commercial purposes, and blacking them out. The more redactions required, the more complicated the job.

And in the past half-dozen years, Washington state legislators have turned personnel records into a Swiss-cheese block of exemptions.

“Every year the Legislature adds, on average, a dozen or more exemptions. We’re now up to more than 650,” said George Erb, with the Washington Coalition for Open Government, a nonprofit that advocates for governmental transparency. “Every time they do that, it just makes the act more complicated for everybody. Our own public records lawyers say that … even they have a hard time keeping up.”

One new law mandated that if information was contained in a personnel file, the agency had to contact every employee mentioned to give them a chance to legally challenge the request.

Another required employees to black out victim and witness names from harassment or discrimination investigation records.

Even something that seems like a minor change could be hell on records clerks: Consider a 2020 law requiring redacting the month and year, but not the day, of public employee birthdays.

“If all we had to do was redact that whole column, that would be easy,” Dinaro said. “But no, instead, what we have to do is convert this spreadsheet to a PDF, and then make these tiny little boxes on each row.”

But if a journalist requests the record, the law says the birthdays shouldn’t be redacted at all.

The complications compound until they sound like the setup to a bad joke: A journalist, a commercial data broker, and a curious citizen all walk into a city clerk’s office and request the same set of employee names and birthdays. The clerk has to redact their records three different times in three different ways.

The Legislature hadn’t just added more work for clerks. They’d multiplied it.

Record comebacks

At the local level, at least, some leaders are trying to figure out ways to ease the burden on clerks without cutting off public access.

Spokane City Councilman Michael Cathcart told InvestigateWest he plans to resurrect a 2021 proposal to post many processed records online. It’s a bit like what the city of San Diego and the Oregon governor’s office do.

And Spokane Mayor Lisa Brown is proposing to hire a new records clerk with the midyear budget.

“It’s the right thing to do to have open and transparent government,” Brown said.

Despite the delays, Brown praised the city’s clerks for their thoroughness and attention to detail.

“That’s positive when it comes to public records,” she said. “The issue is speed and capacity.”

In a statement, the clerk’s office indicated they had long been under-resourced and overwhelmed. The city has three clerks dedicated to handling requests sent to their office, along with another who splits her time working on fire department records. Since 2014, the clerk’s office handles a big chunk of police records as well.

The clerk assigned to InvestigateWest’s request for the record logs had never redacted that kind of document before. She was handling more than 100 other requests at the same time.

“We’re going to add capacity,” Brown said. “But we’re also going to look at best practices and other technologies and ways to improve the system. … At least one person mentioned the idea that AI could be a part of this.”

Brown said one city they’ll be looking to is Vancouver, Washington, just across the Columbia River from Portland.

While InvestigateWest is still waiting six months later for Spokane to hand over over a week’s worth of communications involving the mayor or city administrator, Vancouver completed the whole thing in only eight days.

The average Vancouver request in 2022 only took 10 days to finish, a third the time of Spokane and a fifth the time of Seattle.

Vancouver City Attorney Cary Driskell didn’t name any particularly zesty secret sauce responsible for Vancouver’s speed. Sometimes they do charge fees for particularly voluminous requests. Often, they’ll save time by disclosing more than they have to. They’ll create records like the records logs in a way that makes them a lot easier to release.

“These are presumed to be records belonging to the public, and they have a right to see them. I don’t think all jurisdictions have had that approach,” Driskell said. “Vancouver puts up quite a lot of resources towards getting these responded to in a timely fashion.”

Sometimes, that’s the unsexy answer to fixing a broken records system: Spend money.

In 2020, Portland created a special initiative, the “Police Records Backlog Project,” that tapped legal staff, private attorneys, and even Portland Police Bureau recruits to dig through the backlog. And today, the team reports, they’ve honed their process, which means quicker responses and lower fees.

“There are too many public agencies at all levels who do not see public disclosure of information as a core function of government,” Bottomly said. “They see it as an added burden that they must carry. They don’t budget for it, they don’t staff for it.”

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. A Report for America corps member, Daniel Walters covers democracy and extremism across the region. He can be reached at daniel@invw.org.