Iconic Spokane artist Harold Balazs left his mark and his art is on display at the MAC

Harold Balazs passed away in 2017, but one of the greatest artists in Spokane history lives on through his work.

There’s the 1978 Centennial Sculpture floating in the Spokane River near the Convention Center. There’s the iconic Rotary Fountain in Riverfront Park, which was made with Bob Perron in 2005. There are a number of pieces Balazs created in Seattle, Montana and Alaska.

A convenient way to experience Balazs’ unique and provocative art is to check out his exhibit at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture from Feb. 3 to June 2.

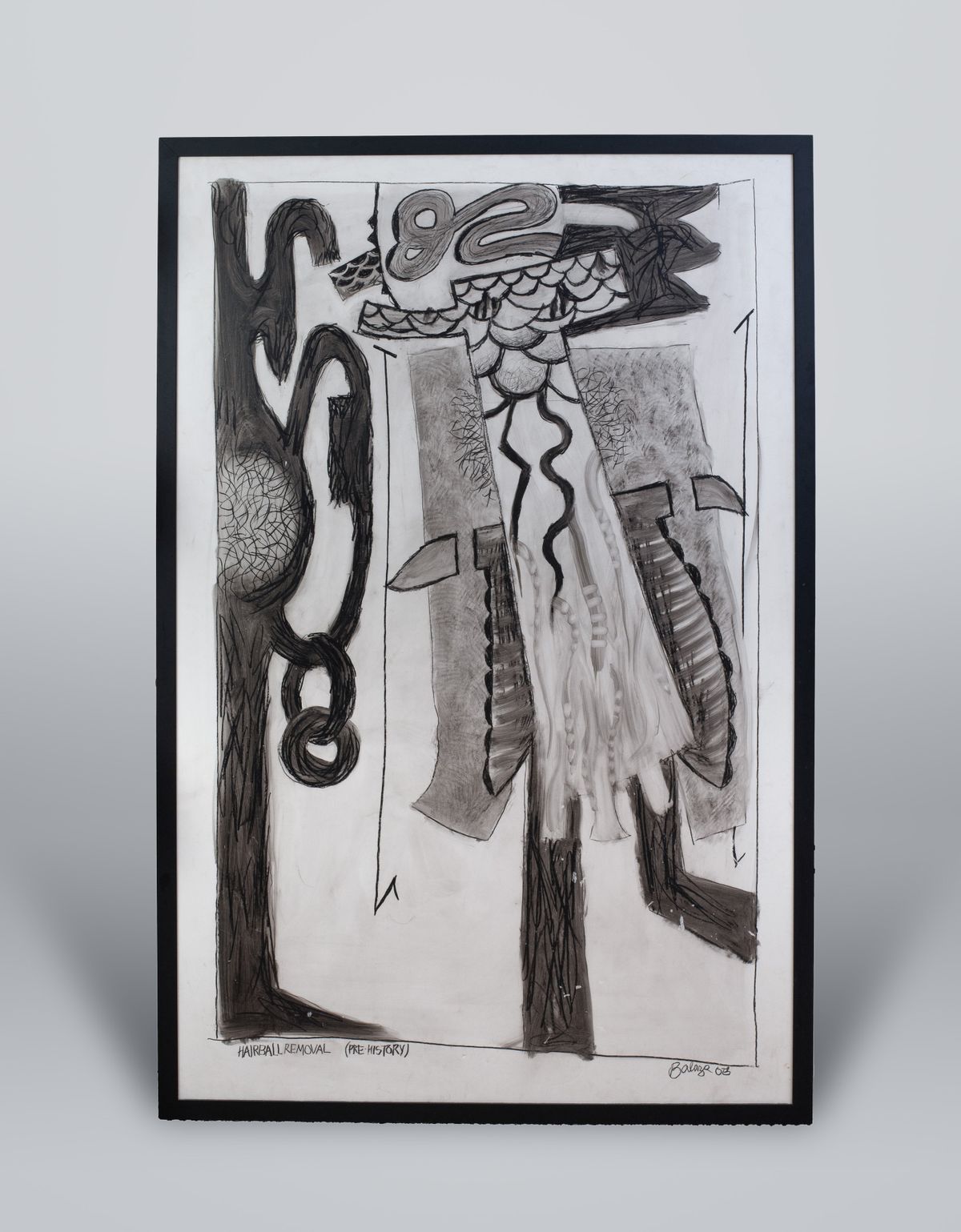

“Harold Balazs: Leaving Marks” is an exhibition of 30 mixed-media works. The collection includes sculptures in copper, lead, wood, metal and styrofoam. Many of the works have not been on public exhibition in decades and have never been shown together as a single collection.

“I’ve lived in a lot of cities and there is not a place where I’ve been where an artist carries as much weight and identity of a city than Harold Balazs,” said Executive Director of the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture Wesley Jessup. “Harold is Spokane. He’s our most famous artist and it’s so important for the MAC to recognize and honor his legacy. There are so many amazing pieces that we’ll have on display.”

The collection features Balazs’ Trying to Understand, a ground-breaking 96-inch tall sculpture, created by using a styrofoam base coated with graphite. Another untitled sculpture was carved from lead, which is a most unusual medium for artistic use. Balazs’ industrial background inspired his use of affordable materials not commonly used by other artists.

But that makes sense since Balazs, who was born in 1928 in Westlake, Ohio, was a child of the depression.

“Harold grew up near a steel mill and was attracted to the material from the mills,” Jessup said. “He worked at his father’s sheet metal and air-conditioning business and that impacted his art.”

Balazs’ mother enrolled him in art classes in Cleveland when he was 12. After his family relocated to Spokane during the 1940s, he enrolled at Washington State College and earned a fine-arts degree. After graduating in 1951, he started selling enameled jewelry in Spokane.

Local architects began incorporating his work in their designs.

“There really was no one like him and we couldn’t be more excited about this exhibit,” Jessup said.

“Leaving Marks” is broken down into three sections. “Constructed Realities,” “Making/Life” and “Transcend the Bullshit.”

“The show is broken down this way since the whole premise of this is to present this new collection in a way that allows visitors to get some insight into the forms and archetypal arcs Harold was working with throughout his life, which culminated into his body of work,” MAC curator Anne-Claire Mitchell said. “We decided to explore it from a few different standpoints.”

“Constructed Realities” is an overview of Balazs’ industrial roots.

“It’s interesting seeing Harold introduced to industrial fabrication by his father,” Mitchell said. “Harold was exposed early to the potential of using some of these commercial materials in creative ways. You can see the lifelong practice he grew up with and the ethos of saving and making things in an affordable manner.”

“Making Life” explores how Balazs was inspired by everyday situations.

“Harold saw the creative potential in everything,” Mitchell said. “He would read avidly and learn about other places in the world and he was always involved in his community.”

“Transcend” is about Balazs’ philosophical side and his playfulness. “Harold had a satiric and playful approach,” Mitchell said. “He had a childlike side to his personality and he was a trickster.”

Balazs’ art is abstract but his message was not and it was evident that he believed his art was for the people.

“Harold didn’t believe that his art should be tucked away in elite institutions,” Mitchell said. “He didn’t want it to be that his art could only be appreciated by certain people.”

It’s fitting that the MAC is working on securing the Balazs exhibit from a private collector so it will be part of the MAC in perpetuity.

“The person who owns the art is getting older and would like to downsize,” Jessup said. “My perspective is that we would love to have his collection, which can live here in Spokane and can be appreciated by future generations, who need to know the art created by Harold and the story behind the art, which is one of a kind.”