Learning cursive in school, long scorned as obsolete, is now the law in California

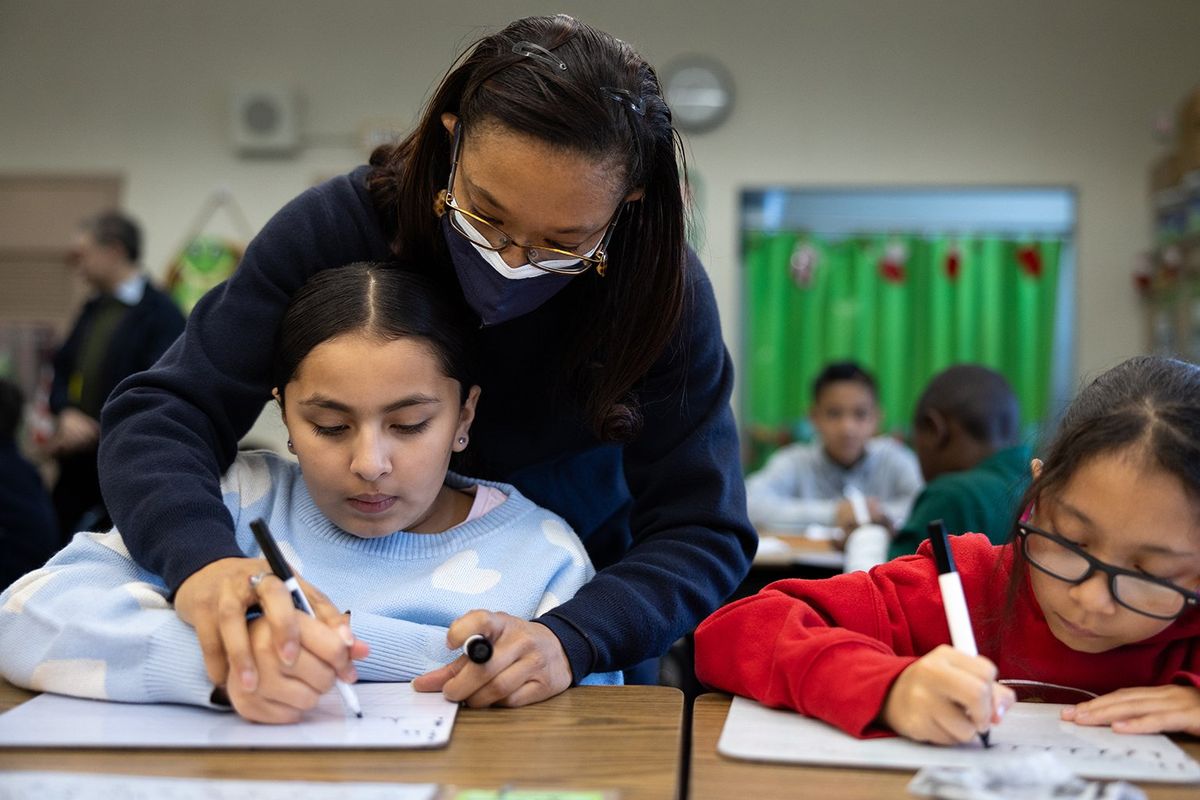

Tyara Brooks helps guide fourth-grade student Aaliyah Miranda-Garcia, left, and Sophia Ortega during a lesson on cursive writing. (Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

LOS ANGELES – Erica Ingber has something of a dark past when it comes to handwriting: The future elementary school principal got a C-minus in cursive in the fourth grade. But she’s ready to follow the curvy ups and downs of a new California law that requires the teaching of cursive writing, which has been cast aside as obsolete in the digital age.

But cursive is making a comeback amid concerns that learning to use a keyboard had superseded handwriting skills that are important for intellectual development – and also that a new generation of students could not write or read the flowing words of historical documents, old letters and family recipes.

“The ability to sign their name in cursive is important for future job applications, writing checks, signing medical forms, obtaining driver’s licenses, and voting,” said Assembly member Sharon Quirk-Silva, D-Fullerton, a former teacher who sponsored the new law. “Every child should be exposed to learning – as well as the benefits of – cursive writing.”

The research on cursive is hotly debated, with some experts saying that it leads to academic gains. Other academics insist that such benefits have not been consistently shown or not shown at all. There appears to be broad agreement, however, that typing should not replace extensive instruction in handwriting – in some form – for young students. And even if printing is good enough, cursive is enjoying a resurgence.

At Longfellow Elementary School in Pasadena, fourth-graders already are carefully practicing their loops, slides and curves.

“For some students, it’s a great alternative to printing and it helps them be more accurate and more careful with the writing,” said Ingber, the school’s principal. “And then for others it’s just another thing that is difficult for them.”

Across the country, cursive writing had been substantially abandoned for more than a decade in favor of teaching elementary school students to type after they learned to print letters. This anti-cursive trend was reinforced in 2010 when many states adopted the influential Common Core learning standards, which had dropped cursive entirely. Under the Common Core framework, states had limited flexibility to teach any skill that fell outside that curriculum. So many chose not to require cursive.

By 2016, only 12 states mandated learning cursive. Since then, however, 11 have reconsidered and restored cursive, with the latest being California and New Hampshire, according to a site that tracks cursive instruction.

Even before the new law took effect on Jan. 1, cursive was a California learning goal in grades 3 and 4, but the state and school districts had not enforced its teaching or tested to see whether students had mastered it. Moving forward, handwriting instruction for grades 1 to 6 is to include writing “in cursive or joined italics in the appropriate grade levels,” the law states.

The directive leaves room for flexibility. Pasadena Unified will begin cursive in second grade, setting aside first grade for students to learn to print.

Ingber recalls that her mother was shocked that she would bring home a C-minus in anything, handwriting or otherwise, but the setback did not prevent Ingber from becoming a teacher, teaching cursive herself and becoming a well-regarded principal.

Pasadena Unified is in the process of purchasing materials to comply with the cursive law, because many publishers had stopped including it in their materials, said Helen Chan Hill, the district’s interim chief academic officer.

Even so, Ingber knew just where to turn for a glimpse of the cursive future: Room 214 and fourth-grade teacher Tyara Brooks – who aced cursive as a child and never lost her love for it.

Brooks has never stopped teaching cursive. Last month, she announced the beginning of cursive lessons – and excited oohs and aahs reverberated around the room. Apparently, none of the students had learned cursive in third grade, although a few had experimented on their own, and they were eager to write in this grown-up way.

“People like George Washington, Abraham Lincoln – and of course we know very well Alexander Hamilton – would really be super excited if they came in and saw what you’re doing,” Brooks told them. “Because you’re starting to write like they learned to write. And you’re actually ahead of some adults and some college students because they haven’t learned how to do this yet.”

Nine-year-old Miral Shalalfeh saw the upside: “When I learn cursive, I could teach my dad and mom and my grandparents and everybody.”

Brooks projected signatures of people familiar to all the students: the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Walt Disney, Taylor Swift and, somehow, Vincent Price.

“When you’re able to write in cursive, that’s something that you can own for yourself,” she told students. “You can make it any way that you would like – as long as you’re following the rules, of course. … I’ve seen Ms. Ingber where she writes her signature, and it takes like two seconds to do because she’s so good at knowing the rules.”

The teacher also projected an image of the original U.S. Constitution, written in cursive.

Being able to read historical documents in their original form is another benefit of learning cursive, which also helps with handwritten holiday cards and letters from grandparents, she said. Plus, cursive is easier on the hand and faster.

In printing, she noted, you start from the top down, whereas cursive goes from the bottom up.

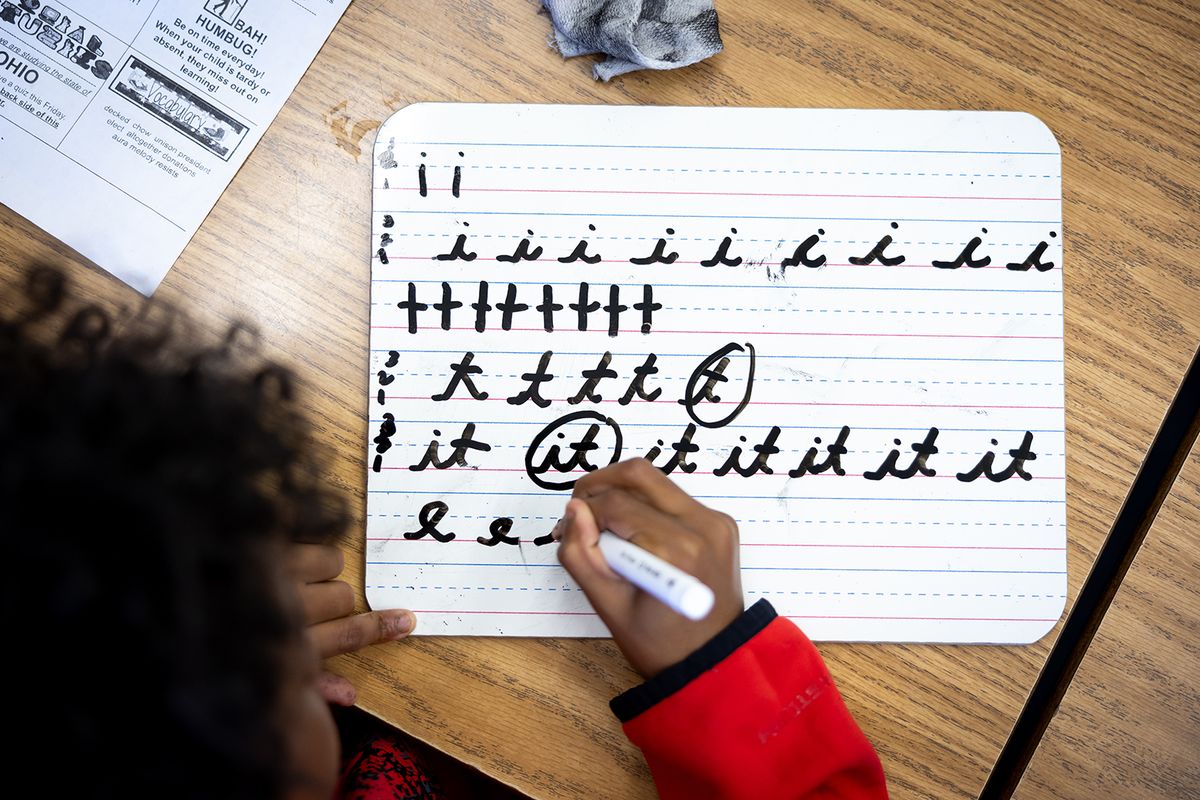

Brooks described the looping technique for lowercase “L” and then worked her way through lowercase “T,” “I” and “E,” explaining the differences between print and cursive versions and getting to the fine points of cursive: A cursive lowercase “E” can look like a cursive lowercase “L” if students aren’t careful.

Students also began connecting letters for a few simple words.

Soon, the fourth-graders were chanting, over and over: “Slant up, stay on the line, come down, pull away.”

“I already knew how to make an ‘I’ in cursive,” said Genesis Aguilar, 10, “because my first and last names have an ‘I’ and I like to write my name. I’m still practicing different kinds of signatures.

“I’ve always wanted to write in cursive. When I write like a lot, my wrist starts to hurt. But in cursive, it’s relaxing. Because you don’t use as much pressure.”

For older students, cursive backers say that taking notes in cursive can be more effective than typing notes, because writing by hand requires more comprehension and synthesis. They acknowledge, however, that typing on a keyboard is more effective at transcribing exactly what a teacher says.

Joining in official support of California’s cursive legislation was the Los Angeles County Office of Education.

“Most students with reading difficulties also struggle with handwriting and writing structures in general,” the education office stated in comments in support of the bill. “As a general rule, reading and writing go hand in hand, and the ability to actually handwrite is key in the development of young learners.”

Under the bill, instruction in cursive would “be standard across our state. Every student will be taught this important skill.”

Some proponents say students who are dyslexic can derive particular benefit from writing in cursive.

But the county education office’s reasoning, as quoted in a legislative analysis, did not make a distinction between the benefit of printing versus cursive.

Rather, the argument extolled the benefits of writing by hand versus emphasizing keyboarding too early or too much:

“The mechanics of handwriting follows a sequence initiated in the brain, similar to reading – the sound is heard and processed, a letter attached and visualized, then translated into a shape on a page and produced with motor skills that reinforce the direction of lines and shapes to form letters.”

Handwriting, the argument goes, reinforces reading skills such as visual tracking, reading left to right, as well as capitalization and punctuation rules, spelling and vocabulary.

A body of research supports this view, but not so much an advantage of cursive over printing.

“Since at least 1922, elementary school children in North America have been taught print first, and then cursive writing in or around third grade,” according to an early legislative analysis. “However, practices vary by country and have changed over time. Schools in some countries teach only cursive, some teach print and cursive simultaneously or sequentially, some do not teach cursive at all, and some leave the choice up to individual teachers.”

All sides in the debate can find research to support their view. But the return of cursive engenders rare bipartisan accord in California and in other states. In the California Assembly, the bill to require cursive passed 79-0.

Originally, the restoration of cursive was “primarily coming from the right,” said Morgan Polikoff, an associate professor of education at USC’s Rossier School of Education. Promoting cursive was a jab at the Common Core and what critics saw as overreach on education policy by the Obama administration. Cursive also was traditional and provided direct access to historical documents.

On the left, “it’s much more about creativity and the arts” and potential benefits for dyslexic kids, Polikoff said. “There are reasons for everyone to love it.”

Polikoff doesn’t oppose cursive, but sees it as something of a sideshow.

“What I think is really wild is that we’re devoting any attention to it at all when chronic absenteeism has doubled and achievement fell off a cliff and we’ve got all these other crises and culture wars in the schools,” he said.

“But the one thing we can all agree on is that we must mandate cursive.”