Tom Bailie, nuclear ‘downwinder’ who led rallying cry against ‘industrial recklessness’ at Hanford, dies at 76

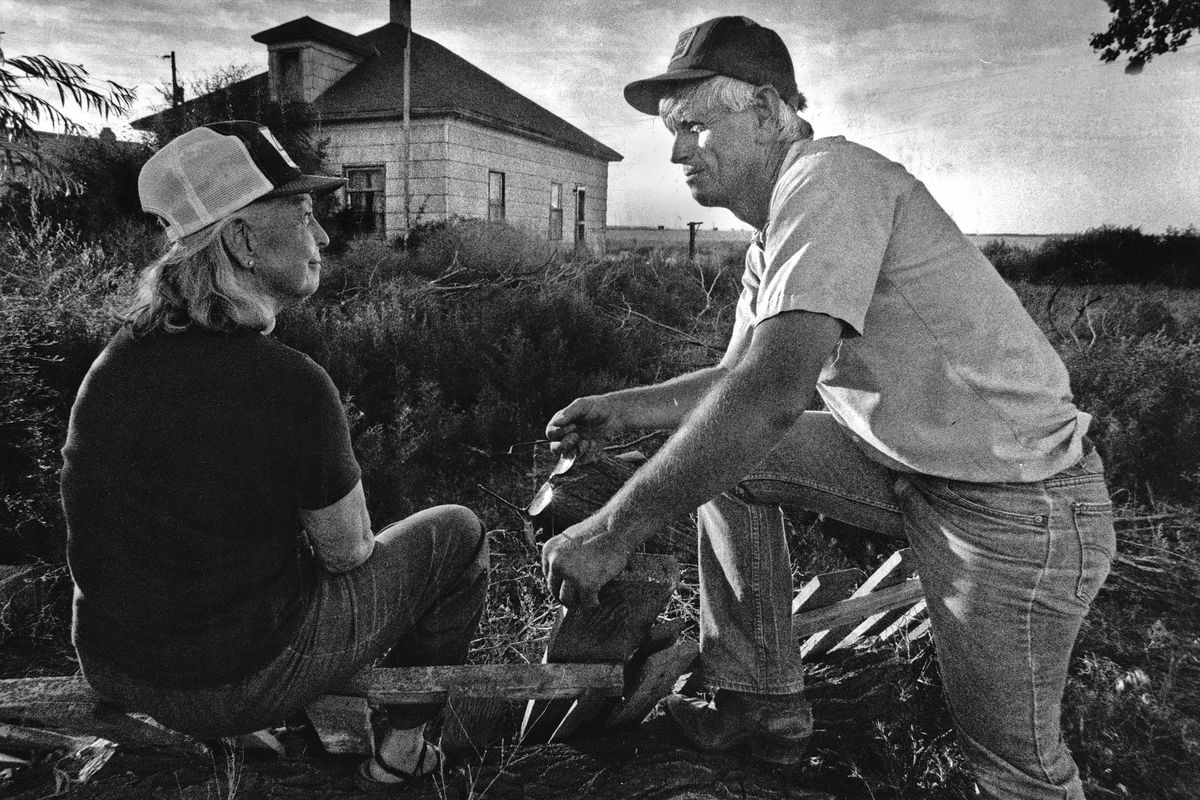

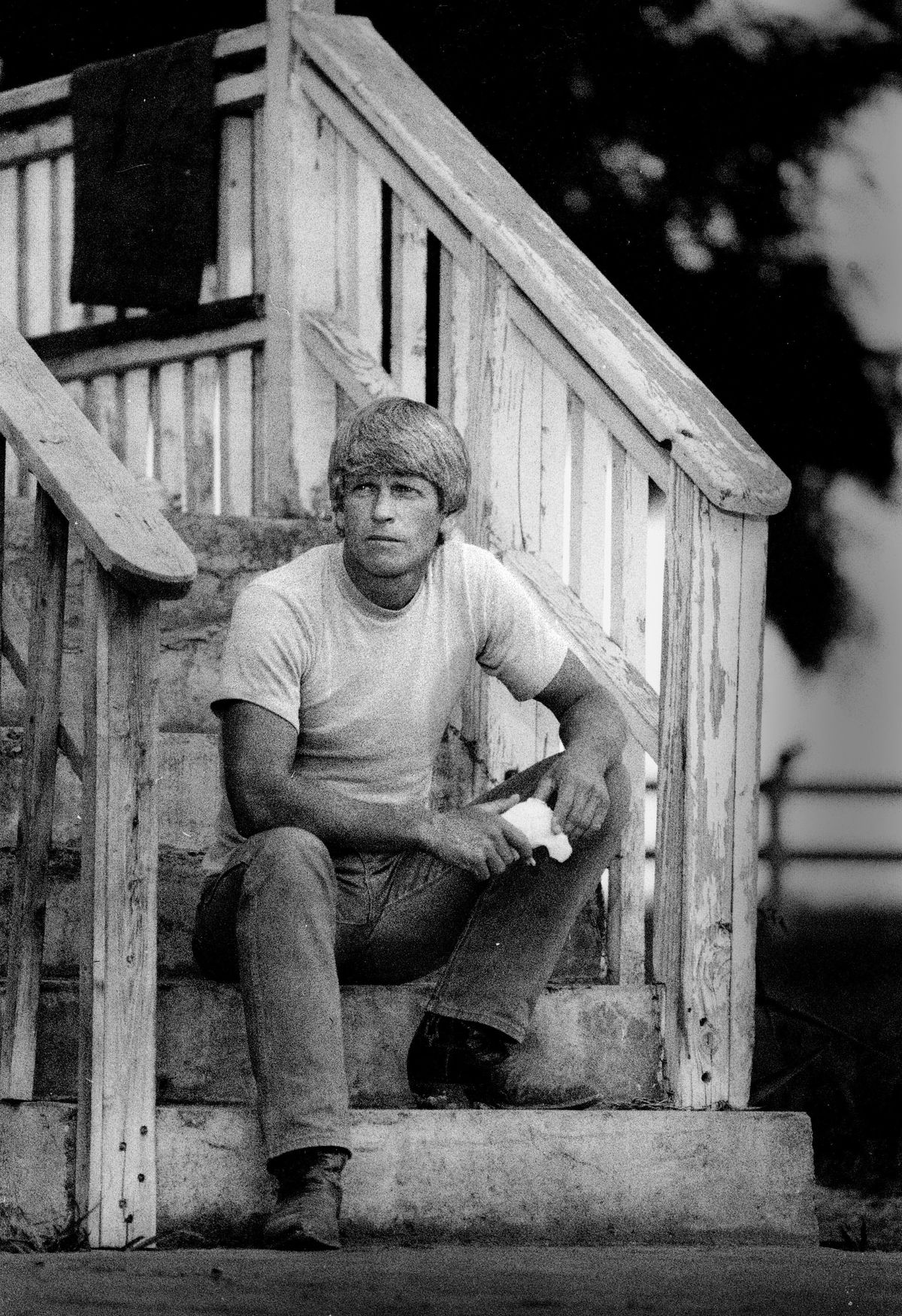

Hanford downwinder Tom Bailie stands in 1985 in one of the many fields that three generations of his family worked going back to the 1940s. In the background is the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. (Christopher Anderson/The Spokesman-Review)

Tom Bailie, an outspoken Eastern Washington farmer who became a prominent voice for thousands of people secretly exposed to radiation from the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, has died.

Bailie, 76, died Jan. 4 at Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland. After suffering from Parkinson’s disease and anemia, he recently was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia.

“When I took him to Kadlec, he told them ‘I’m a downwinder.’ He let them know,” said his sister Mary Reeve, who also lives on a farm in Hanford’s shadow.

Bailie stood out as a charismatic leader for those nuclear “downwinders,” said Sarah Fox, a doctoral candidate who wrote a 2014 book about Nevada Test Site downwinders and who has helped Bailie organize his archives.

“Tom had an instinct for how to keep the Hanford story in the public eye,” she said.

Her history students, recently dispatched to Bailie’s property, found hundreds of letters from downwinders and 20,000 paper cranes from hibakusha, Japanese victims of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

Thomas Lee Bailie was born in Pasco on March 10, 1947. Four years later, his father, Maynard, won a government land lottery for World War II veterans, and the family moved to a 14,000-acre farm near Mesa, across the Columbia River from Hanford. The Atomic Energy Commission had restricted this land during World War II because of its proximity to Hanford’s secret plutonium plants. The AEC required the farmers to establish small dairies, where they tested milk weekly for radiation – signaling a connection between Hanford and the farms.

Bailie was a sickly child, suffering from stubborn skin sores and a paralysis at age 5 that put him in an iron lung. He started first grade in leg braces and was diagnosed with sterility as an 18-year old.

His mother, Laura Lee Bailie, worked before her marriage in the 1940s as a secretary in Berkeley to Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the Nagasaki bomb, made of Hanford plutonium. She gave her four children a daily pill – likely potassium iodide, which blocks the uptake of radioactive iodine in the thyroid gland to prevent cancer. But she was closed-mouthed her entire life about her top-secret work for the Manhattan Project, the race to build the atomic bomb during World War II.

Bailie addressed his childhood medication in the 2020 book “The Hanford Plaintiffs: Voices From The Fight For Atomic Justice,” by downwinder Trisha Pritikin.

“We seemed to have escaped thyroid radiation from Hanford’s radioiodine thanks to that daily pill… the other kids who lived around us have thyroid disease or thyroid cancer,” Bailie said.

In 1985, Bailie aired his concerns for the first time in a Spokesman-Review article titled “Hanford Downwinders: Living With Fear.” The main photo shows Bailie in a field of corn, the Hanford nuclear plants behind him.

The Reagan administration had recently restarted Hanford’s shuttered PUREX plutonium plant for a new arms race with the Soviets, triggering political opposition outside the pro-nuclear Tri-Cities – and pressure to release documents on Hanford’s environmental safety, most still classified until 40 years after the end of World War II.

Bailie’s neighbors shared their “death map” of early heart attacks and cancer deaths. They also described the grisly births of deformed lambs in 1961, when eight Hanford reactors were running, and the occasional appearance of men in protective suits sampling vegetation without revealing the reason. Bailie confided that he was overwhelmed by his neighbors’ stories, concluding that his ill health “was no coincidence.”

The Spokesman-Review story drew national attention, including a parade of network celebrities like Connie Chung of CBS, who perched on Bailie’s tractor while listening to his folksy, sometimes startling, stories. He appeared on Bill Buckley’s “Firing Line” show in Pasco in 1989 with a Spokane reporter and a Hanford official to debate nuclear safety.

Hanford officials initially brushed off Bailie’s concerns.

Don Elle, chief of the U.S. Department of Energy’s environmental safety branch, said the farmers hadn’t been studied because “we wouldn’t expect to see anything.”

Not everyone in Bailie’s community welcomed his message.

Some told him to shut up out of fear of having their crops stigmatized as contaminated. His wife, Linda, disliked his sessions with reporters, sheltering their four adopted children from the furor. But Bailie continued, obstinately.

Less than a year later, his suspicions gained traction. The federal government, responding to newspaper and activist groups filing Freedom of Information Act requests, released 19,000 pages of formerly classified Hanford reports in February 1986. More would follow.

They revealed chronic off-site contamination during Hanford’s first 20 years – with the heaviest releases eventually traced to Bailie’s community. Significant Iodine 131 releases continued until 1956.

The public was especially shocked by the revelation in The Spokesman-Review of a deliberate military experiment called the Green Run. In December 1949, it spread “green” (uncooled) uranium fuel in a 200-mile plume from Spokane to The Dalles, violating Iodine 131 safety limits by 11,000 times at Hanford and by hundreds of times in some Hanford-area towns.

Hanford officials considered, and rejected, health warnings to nearby towns after several accidents in the 1950s and ’60s. In a September 1954 report to the AEC, Hanford health physicist Herbert Parker warned if farmers were told about radioactive ruthenium particles falling in their fields they would “not be as relaxed as the (Hanford) worker” who recently said “living in Richland is ideal because we breathe only tested air.”

Parker wanted to check local cattle intestines for ruthenium ingestion, but “could not do it without exciting too much comment.”

Hanford’s failure to warn the farmers angered Bailie.

“I’m not anti-nuclear, but what they did to us was industrial recklessness and stupidity,” he said.

As the Hanford story unfolded, Bailie was profiled in articles and books. He continued his downwinder activism for the rest of his life and was a plaintiff in a 25-year federal lawsuit against Hanford contractors for health damages, which finally concluded with some modest settlements in 2015. Bailie did not get a settlement because he didn’t have thyroid disease.

He was preceded in death by his parents, his wife and his daughter Meggin Bailie. He is survived by daughters Jill Bailie, Tomalin Bailie, Tamsyn Bailie, son Zackary Bailie, sisters Reeve and Suzie Bailie, and brother Terry Bailie. He also leaves eight grandchildren.

A graveside memorial is scheduled Feb. 10 at 1 p.m. at Mueller’s Funeral Home in Kennewick.