A bill to preserve historical files and artifacts starts with Lakeland Village, which once was a school

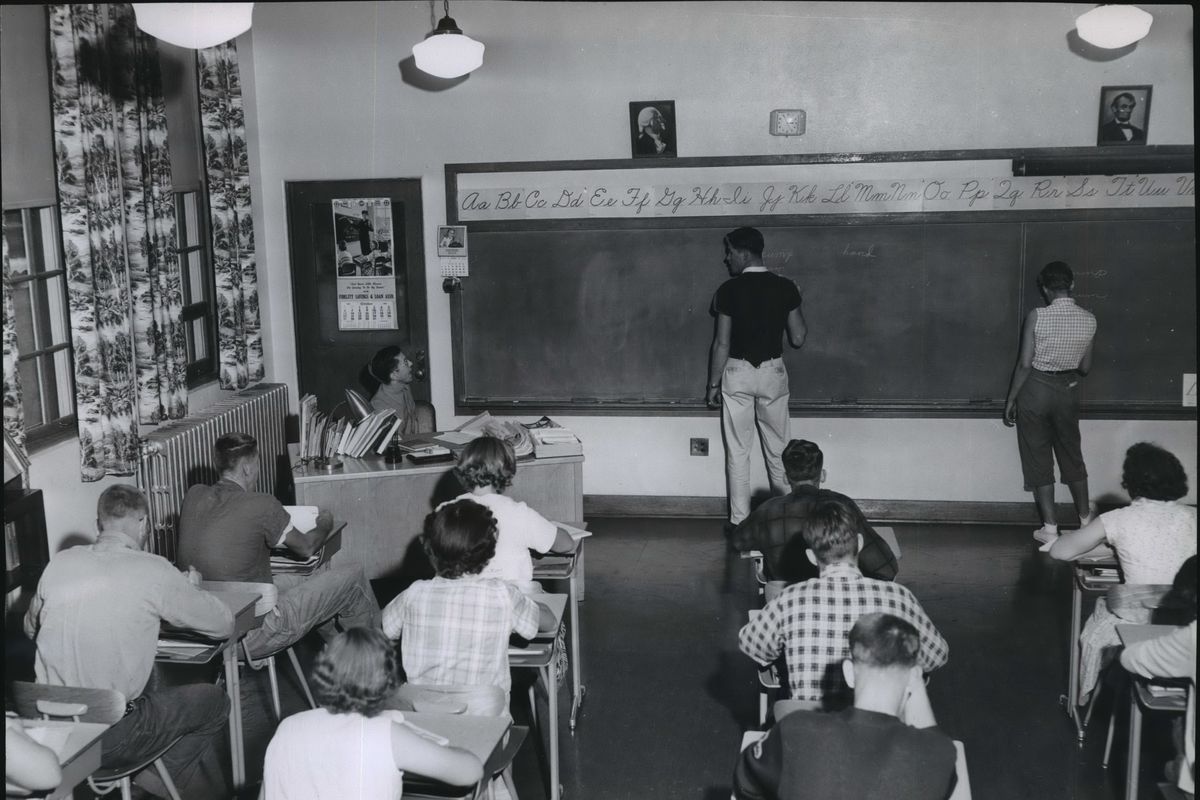

Classroom scene in Lakeland Village. Photo dated Dec. 5, 1957. (Spokesman-Review archives)

Ryan Grant is determined to keep the history of Lakeland Village alive.

The Michael Anderson Elementary School librarian delves into stories about Lakeland Village students dating back to the mid-1900s, teaching his pupils about inclusion and disability awareness.

To fuel his knack for history, he’s also a strong supporter of a bill hoping to preserve historical records and artifacts detailing the treatment of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities at Lakeland Village.

His favorite story to tell? Jimmy Rhodes, the basketball star.

Jimmy showed up at Lakeland Village, located in Medical Lake, when he was 5 years old. Originally named The State Custodial School, Lakeland housed more than 1,000 children with disabilities.

“If you were deaf or had any kind of disability, you probably went to Lakeland Village because schools weren’t equipped to work with kids who had special needs,” Grant said in an interview.

In the early 1950s, Lakeland was on the sports circuit and would play other schools in the Medical Lake area. Rhodes had an untraditional shooting style and wasn’t the most outgoing kid, but he was a great basketball player, Grant said.

“I like to talk to the kids about how if he was around today, he’d be on our local high school varsity basketball team, but because we didn’t have the appreciation for differences back then, he was out there (at Lakeland),” he said.

Due to the late 1960s disability rights movement and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the school shifted its focus toward caring for higher-needs children, resulting in fewer referrals to Lakeland.

Lakeland Village is now a rehabilitation center offering training, education and health care to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, including intermediate and nursing care. Housing around 210 residents, the facility assists in daily living and life skills, as well as therapy and onsite employment opportunities.

“What we think of as an appropriate learning environment has changed a lot over the decades, telling that story through the Lakeland lens is critical,” Grant said.

Legislation working to maintain Lakeland’s records is progressing toward a House floor vote. The bill unanimously passed through the Senate on Feb. 13 and passed out of the House Government and Tribal Relations Committee on Wednesday.

The bill instructs the Division of Archives and Records Management to collaborate with various institutions, including the Department of Social and Health Services and the University of Washington Institute on Human Development and Disability, to create a preservation plan for organizing, cataloging and storing Lakeland Village’s historical documents. The plan must be submitted to the Legislature by Sept. 1, 2025.

There are 3,000 patient file boxes at the Village and 18,000 more at the Tumwater, Washington, retention center, which are kept for 75 years before they are destroyed, said Brian Hatfield from the Secretary of State’s Office.

“Those records contain the stories of real people’s lives,” Stacy Dym, executive director at the Arc of Washington, testified on Jan. 23. “… They matter to our collective story of who we are as the people of Washington state and how we have cared for people with developmental disabilities over the decades.”

Dym compared the boxes of records to her “grandmother’s attic,” as many are unprotected, uncatalogued, stored in dilapidated buildings and deserve the chance to be studied, she said.

If the bill becomes law, records cannot be destroyed until 2026 while the preservation plan is ongoing. The plan must evaluate record and artifact conditions, detail preservation measures, allocate a preservation budget, pinpoint at-risk artifacts and establish public access to historical documents, with a goal to digitize many of the files.

Rep. Leonard Christian, R-Spokane Valley, applauded the Lakeland Village faculty for its work keeping the fire away from the facility during the Spokane County wildfires last summer and protecting the residents who live there.

“I appreciate the fact that we’re keeping these very important records,” he said.