Spokane Schools grateful for levy passage, but regrouping after bond fails

As the dust settles after Spokane Public Schools’ first failed bond since 1967, the district will seek community input on a potential future tax ask for aging facilities that staff say need updating.

In the current economic landscape, they were asking voters to approve a tax on themselves, and Superintendent Adam Swinyard said he was aware of rising property values. With that in mind, the district reduced the total amount of the bond from the near-half-billion ask approved in 2018.

A work group previously determined a list of projects to the tune of $400 million, but the district whittled those down to the projects on February’s ballots.

While its levy passed in Tuesday’s election, Swinyard said the district is soliciting community feedback to design a bond proposal more appealing to voters. He said he’s already heard suggestions to reduce the total ask or amend the list of major projects. The district is considering these options but remains steadfast that regular maintenance is necessary on its 57 schools.

“What I hear almost universally is there’s a recognition that you have to take care of and maintain your facilities,” Swinyard said. “I hear that loud and clear. So the community conversation is, what’s the best way to do that moving forward given the economic realities?”

He didn’t speculate on which projects or schools may not make the cut in a more conservative plan B but said safety would remain his priority.

“The ones that are weighing heavily on my mind are the schools that have significant needs for repair as it relates to creating a safe environment for our kids,” Swinyard said, listing limited elevator access at the three-story, 100-year-old Adams Elementary as a safety concern for students with special needs.

Under the bond proposal that failed in Tuesday’s election, Adams and Madison elementary schools would have been torn down and replaced.

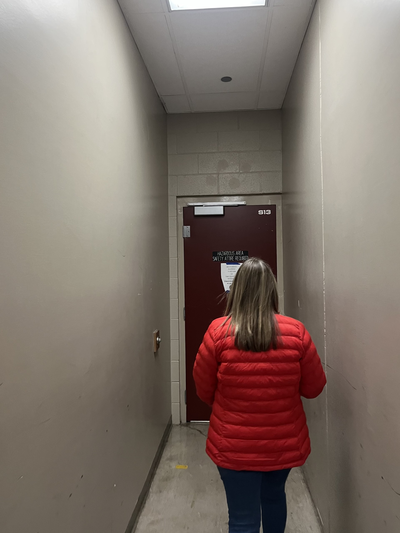

Children with special needs are also top of mind for Madison Elementary School Principal Heather Holter. Her 75-year-old school, with no air conditioning, too few bathrooms and energy-inefficient windows from which heat and outside noise bleed into classrooms, is home to three separate special education classrooms.

These classrooms are relegated to portables outside, due to the fact they have bathrooms built in and reliable heating and air conditioning unlike the main building, though Holter would like more intermingling between students in these programs and those in general education.

“For social justice reasons, it’s never felt good to me that they’re out there and we’re in here,” Holter said.

Thinking of a reconstructed school, she’d imagined a two-story building wrapping around a courtyard playground with equipment accessible to students with special needs or in wheelchairs, a separate cafeteria, gym and auditorium space to replace their “cafe-gym-atorium,” that functions as all three, and a roomy entrance vestibule for visitors to wait in.

She also eyes necessary functional updates to the school: a repeatedly leaky roof with layers of patches and past repairs, ceiling tiles that fall down and a fickle boiler. One day, Holter needs a portable heater to stay warm in her office, the next, she struggles to cool off.

Holter’s office thermostat is set in the mid-60s, but the temperature is warmer than 70 degrees. When she twists the knob, it hisses at her.

“There’s something funky going on again,” Holter said. “It’s just how this building talks to us. It’s just saying, ‘I can use some work. I could use some updates.’ ”

On August and September days when the temperatures rise to the mid-90s and wildfires pollute the air, preventing teachers from opening windows, Swinyard said the district would cancel school at Adams and Madison since they don’t have air conditioning.

In addition to improvements staff said are necessary for the health of the school itself, Holter said there’s a certain level of pride fostered in students when they learn in a new-and-improved facility. Building that school spirit in students at a young age is an investment they can carry with them throughout their educational careers, she said.

“One of the things about elementary schools is you think of the foundation of a house. We’re the foundation really for their learning,” Holter said. “If we can get our kids as prepared as we can for their future, then we’ve done our part for the middle school, the high school and what lies beyond for that.”

North Central High School would have also seen renovations under the bond, though that wouldn’t have been the first time the school has had major work done under a bond initiative.

The school is a jigsaw puzzle, “the SeaTac of schools,” said Principal Tami McCracken. Portions were updated or annexed under the 2009 and 2015 bonds; as such, some classrooms glisten with fresh paint and natural light from windows. In others, English teachers are holding classes in former science labs. Educators were hoping for renovated gyms, modernized rooms for some specialty academic offerings, including their culinary arts and engineering programs, and updates to the theater that would have been paid for under this year’s failed bond.

The school’s specialty trade programs, like engineering and culinary arts, have outgrown the current facilities. These programs are modern, McCraken said, while their classrooms are outdated and limit the capabilities of instruction.

“The classes have changed, and the needs of students and the needs of our economy and the needs of our education system have changed in the 42 years since the school is open,” McCracken said. “And yet the modernization at the south end of the building has not, so we’re in spaces that don’t meet the needs of the education we’re trying to do at this time.”

The school’s robotics classes are taught in a former biology lab, with an attached greenhouse where a 3D printer and other boxes of engineering equipment and robotics kits are piled high against the glass panes. Cords dangle from the ceiling, making up for a lack of outlets at lower altitudes.

Their kitchen is a time capsule from 1981, designed for home economics courses, with several battered and sagging stovetops and industrial kitchen appliances haphazardly set around the room. They’re a reflection of the modern wishes for the course, called ProStart, a career-readiness course for the food industry.

“The design was around, how do you bake cookies? And how do you cook for your family? That’s how this kitchen was set up,” McCracken said. “ProStart is more, how do you make a living?”

Renovations on the oldest classrooms were also slated under the bond. Riley Moore teaches ninth and 12th grade English in a non-updated classroom.

“Resource-wise, it would make a really big difference for me, as far as having tools of teaching would be nice, and just a different design in my classroom, maybe some more space,” Moore said. “I think there’s a part of pride that you take in how your building looks.”

He wants an updated school for his students to foster school spirit, as is the case at Madison. When his students see other district high schools get updates, he said they can’t help but envy more recently updated schools like Ferris and Lewis and Clark, for example.

In his un-renovated classroom, he teaches his kids that struggle builds character.

“Some of the stuff I wear with pride and the struggles that we have here, I do kind of like them on some level, and I think part of that is a positive attitude,” Moore said. “I tell my kids all the time that I like that we have to work a little harder sometimes, and I think that gives you a badge to wear.”