Plans to build Washington’s largest wind farm held up again amid local controversy

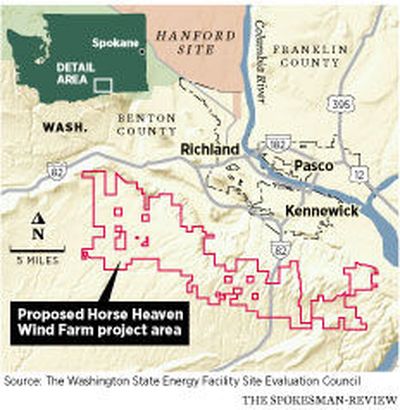

Nestled between the Yakima Valley and the Columbia River in southeast Washington, the fate of a wind-whipped range of hills has been subject to a yearslong dispute about energy, tourism, the past and the future.

That stretch of land in wine country near the Tri-Cities may become home to the state’s largest wind farm, dotting miles of rolling hillside with more than 100 white turbines. In 2021, Colorado-based company Scout Clean Energy asked the state for permission to build the Horse Heaven Hills Wind Farm.

Last week, the state Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council was scheduled to vote on whether to recommend Gov. Jay Inslee give developers the go-ahead to break ground. But complicated details and conflicting opinions by residents who live near Horse Heaven Hills prompted the council to extend the voting deadline to April 30.

This year, Inslee is asking lawmakers to spend another nearly $1 billion to mitigate climate change through clean energy, environmental justice and transportation projects.

Money for that $941 million investment would come out of revenue from what the governor considers one of his biggest accomplishments in his more than 10 years running the state: the Climate Commitment Act, Washington’s landmark climate policy.

Elected officials have vowed to phase out coal from the state’s energy economy by the year 2025 and to reduce 95% of carbon emissions by 2050 through the climate policy. As lawmakers and residents grapple with how to produce clean power while meeting increasing demand for electricity, there is much to consider.

But one thing’s for certain: Big changes are on the horizon.

‘People pay for scenery’

If the state approves the Horse Heaven Wind Farm, then summer 2025 is the earliest construction would begin. That date could easily be delayed if people submit petitions for reconsideration or an appeal on the project makes its way up to the state Supreme Court.

Concerns by ecologists over risks posed by populations of ferruginous hawks cut the original plan to build more than 100 windmills down to 62, said Dave Kobus, senior project manager with Scout Clean Energy. The company is hoping to convince the Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council to reconsider and allow them to move forward with their original plan.

“We’ve got to find flexibility, so turbines are not isolated because of a twig on the ground (that means) a nest is no longer viable,” Kobus said. “We cannot build a turbine within 2 miles of twigs on the ground that happened to be a nest two years ago.”

Developers of the project do not know what power company they will contract with or where electricity would be sent, Kabus said.

“There are requests for proposals by regional utilities,” Kabus said. “So we’ll see where that ends up. It’s just so hard to sign preliminary agreements when you don’t have permits. We do hope this is the last extension.”

The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation are among the groups opposed to the wind farm. Tribal representatives did not respond to a request for comment on this story, but a testimony letter sent to the state last year explained the project would damage the cultural and historical significance of the Horse Heaven Hills.

Millennia before white colonial settlers took over the West, thousands of Native families, tribes and sub-bands inhabited the Horse Heaven Hills region, wrote Johnny Jerry Meninick, deputy director of culture for the Yakama Nation.

“When the United States came, they came with the purpose of eliminating us with armies,” Meninick wrote. “They also separated us and took our elders to stockades and children to boarding schools. They kept able men to help build new roads, harvest timber. … In many different ways, that same principle applies here.”

Meninick said the Yakama Nation reserved the right to maintain resources around Horse Hills.

“Our elders understood what the Treaty meant when it reserved inherent rights to fish and gather,” Meninick wrote.

A small community group called Tri-Cities C.A.R.E.S. (Community Action for Responsible Environmental Stewardship) argues the project will drive down property values in the area and pose obstructions to emergency planes or hospitals in the event of a wildfire on the hills.

Paul Krupin said he and his fellow C.A.R.E.S. board members recognize the importance of renewable energy in the wake of climate change.

“This is just a really poor solution,” Krupin said in an interview. “This project? First, it doesn’t do anything to climate change at all. And second, it doesn’t produce power when we need it.”

The Tri-Cities is among the fastest-growing parts of Washington. Between 2010 and 2020, the region saw the most population growth per capita out of all of Washington, according to U.S. Census data.

Krupin said building turbines on the valley’s southern skyline will decrease property values and ruin views for all the new residential neighborhoods being built less than 10 miles away.

“People will be seeing turbines from their living rooms, their front doors,” Krupin said. “… People pay for scenery. People like natural environments, and people are willing to pay less when energy infrastructure is in their view.”

Another argument cited by people opposed to the Horse Heaven Wind Farm is that the project will get in the way of airplanes and helicopters fighting fires.

‘Overhead obstructions’

Across the state in Olympia, conversation brews about the project.

Last week, Rep. Stephanie Barnard, R-Pasco, celebrated that her bill intended to put up guardrails surrounding renewable energy projects in the state passed out of the House Environment and Energy Committee.

The idea for the bill came to Barnard while she was grabbing a meal with Krupin. They began discussing how the Horse Heaven Hills are a high-fire danger area, Barnard said, and wondered how first responders would fight fires with planes if turbines were in the way.

Barnard’s bill picked up local support from Rep. Jenny Graham, R-Spokane. If passed, it would require the Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council or any local municipality to send notice to the state Department of Natural Resources any time they receive an application for a renewable energy project.

The notice would need to include the location and description of the project, along with contact information for the proposed developer. This would allow the DNR to identify potential conflicts between the proposed location and aerial firefighting capabilities, should a fire occur within or around the energy farm.

Although the bill aims to provide siting guidelines for renewable energy plants so aerial firefighting abilities aren’t hindered, these are far from the only obstructions wildland firefighters must navigate across the state.

Cellphone towers, power lines, housing developments, shipping areas or any overhead obstruction can also block firefighting efforts, said DNR Forester George Geissler.

“We have other tactics that we utilize because things of this sort with aerial obstructions are fairly common nowadays,” Geissler said in an interview. “We’ve just learned to work around it.”

In the event of a fire, ground resources – like fire engines and bulldozers – are always deployed first to get to the scene as quickly as possible. Aviation comes in later. If air tankers are necessary, they’re most often used to cool down the fire so ground crews can build containment lines and make sure the fire doesn’t spread farther.

When fires spark, Washington’s counties rely on state and federal agencies when they need air support, including DNR, the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service. Most counties don’t own their own emergency planes.

Geissler noted most fires don’t need aerial support. Less than 1-2% of the fires that DNR responds to in the state require planes. And the majority of firefighting is done on the ground.

Yet people tend to hyperfocus on planes when they think about firefighting, Geissler said. It’s more common to see a fire engine racing to the scene than a plane dropping water or retardant on a fire.

Last July, Benton County firefighters responded to a brush fire that burned more than 400 acres of land and closed in on multiple wind turbines near the Nine Canyon Wind Project, home to 63 turbines.

“We (were) successful in fire suppression on the ground with the fire trucks and bulldozers,” said Benton County Fire Chief Lonnie Click, adding that the department has used planes in the past, but not in the case of last July’s fire.

If a similar fire were to break out near a wind farm, DNR won’t fly planes over or within the turbines no matter their height or size. Instead, ground crews will work around them.

Flying over the turbines not only poses a threat to the plane and the pilot, but also to the turbines. Water weighs 8 pounds a gallon, he said, and can cause significant damage to the blades if dropped from high above.

“We treat all of that type of infrastructure with great care because we’re protecting it and don’t want to damage it,” Geissler said. “… We still have bulldozers, hand crews, engines and the whole nine yards that can work within the wind generation farm itself.”

The only time planes would be able to engage with a wildfire is if the fire burns outside of the wind farm, as aircraft can fly within roughly a quarter-mile radius of the turbines.

To pass, the bill requiring DNR consultations for alternative energy infrastructure has until Tuesday to gain approval from the House Rules Committee. If it passes, it will move to the House floor for consideration.