He unearthed his roots. Now he digs up lost stories of enslaved people.

John Mills never gave his surname much thought – until he learned where it came from.

When he was in his late 20s, Mills dove into his family history, which he knew little about at the time. What he discovered disturbed him deeply.

Many of Mills’s ancestors were enslaved, he learned. His great-great-grandfather, Ned Mills, was the first to adopt the family surname. It was given to him by the man who enslaved him.

“I had all this pride in the last name Mills,” the 53-year-old said from his home in Bloomfield, Conn. “It was the first time I had to really rethink that.”

Using old family documents and consulting with historical societies, Mills’ sister uncovered details about Ned Mills, who grew up on a plantation in Georgia in the 1830s. He was enslaved until June 19, 1865 – the day the Union army arrived in Galveston, Texas, and declared all enslaved African Americans in the state were free. He then toiled for the rest of his life as a farmer and blacksmith.

Mills went to visit the likely burial place of several family members – including Ned Mills – in Kilgore, Texas, in 2003. Based on a few family death certificates, his relatives were buried in the woods behind a Whites-only cemetery.

“It was an emotional experience as I walked past this pristine, well-kept cemetery,” Mills said, adding that just a few of his family members had proper grave markers. “I only exist because these people were able to persist. I started being very prideful of these people who were treated poorly in life and in death.”

Learning about his own family history, Mills said, propelled him to track down other little-known stories of enslaved people and Black soldiers – and share them.

“I spent most of my life not asking questions about African American history and not really being taught about it,” said Mills, who works as a software architect and launched a nonprofit in 2022 called the Alex Breanne Corporation – named after his daughter – to help support his research projects. “I’m doing this work now, and it’s hard work. I run into a lot of problems with a lack of documentation.”

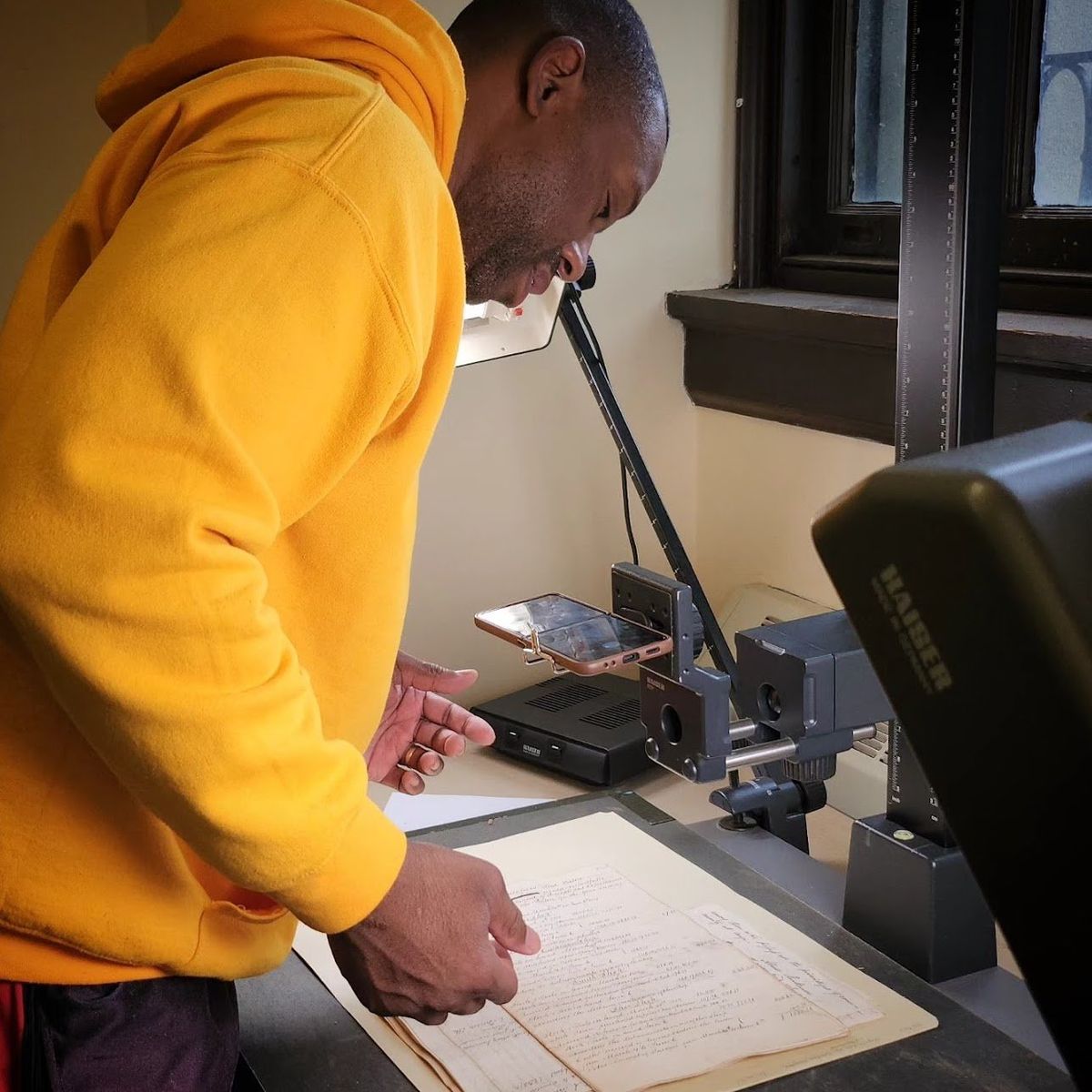

Mills took a genealogy course at Boston University last year to advance his investigative skills. Through rigorous research over the past two decades, he has found harrowing details about dozens of enslaved people and African American Civil War veterans. In some cases, he has connected with their descendants – most of whom, he said, were unaware of their own family history.

“Once I find depths of information, I want to give it to the people I think it was stolen from,” he said.

Mills also tries to educate people about the individuals he researches by creating memorials for them.

“We try to inject these people into the communities where they lived, worked or died,” Mills said.

He added: “I think it’s incredibly important to really tell these stories clearly.”

Wendy Tyson-Wood, president of the Greater Waterbury NAACP, has partnered with Mills on several projects. They are now working on installing a mural in Waterbury to honor an enslaved Black man named Fortune, whose enslaver, a doctor, dissected his body after his death and preserved his skeleton to use for instructional purposes.

Tyson-Wood said she has a strong appreciation for Mills’s work.

“As an African American who is a descendant of slaves, it is important for us to understand our past so we can shape our present and prepare for our future,” she said.

One of the most interesting cases Mills has worked on, he said, is the story of Thaddeus and Mary Newton. They were the parents of Alexander Heritage Newton, an abolitionist and Civil War soldier. Although Alexander Heritage Newton’s own story is somewhat known, “there’s little to no knowledge of his parents, and I think his parents are the story,” Mills said. “The story of these individuals has never been told in its totality.”

Mills took on the task.

Thaddeus and Mary Newton lived in New Bern, N.C., in the 1850s. Mary Newton was a free Black woman, but her husband was enslaved by Peter and Catherine Custis, who were related to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, according to Mills’ research.

Mary Newton left her husband behind to join an abolitionist movement in New York. Not only did she raise money to buy her husband’s freedom, but she also freed other enslaved families in the South. She worked alongside famed abolitionists, including Henry Ward Beecher – Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother – and Henry Highland Garnet.

Now, through his nonprofit, Mills is funding the repair of the Newtons’ headstone at Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven, Conn. Decades ago, it toppled and cracked.

Mills also contacted the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to acquire a headstone for the Newtons’ son Stephen, who fought and died in the Civil War and whose remains were not recovered. It is expected to be installed next to Thaddeus and Mary Newton’s restored headstone this spring.

Mills’ organization is working on several other projects, including one that relates to his own lineage. Through his research, he learned about William Cooper – his third-great-grandfather on his mother’s side. He served in the Union Navy during the Civil War and enlisted in Baltimore in 1864. He was aboard the USS Wyalusing when it took possession of Fort Williams from the Confederacy and reclaimed Plymouth, N.C. – a significant region during the war, given its proximity to the Roanoke River.

Cooper died in 1909 and was buried in Laurel Cemetery – a graveyard in Baltimore for African Americans – which, in the 1950s, was paved over. The Belair-Edison Crossing Shopping Center was built atop it.

“It’s estimated that some 30,000 remains exist under that parking lot,” Mills said, adding that he is planning to purchase a plot at Loudon Park National Cemetery in Baltimore and place a memorial stone there in his third-great-grandfather’s honor.

Mills also petitioned to have a street in Middletown, Conn., renamed to honor an enslaved man named Prince Mortimer, who lived there. Through his research, Mills found that Mortimer was enslaved until he was 87, then sentenced to life in prison after being accused of attempting to murder his enslaver. He died in prison at age 110 and was supposedly buried in the prison’s cemetery, though Mills’s research has pointed him to a different conclusion: He believes Mortimer’s remains were sent to a medical institution. Mills’ effort to rename the street was chronicled last year in the Middletown Press.

By the summer, Mills said, Rapallo Avenue – a downtown street off Main Street that Prince Mortimer would have frequented every day – will have a new honorary name: Prince Mortimer Avenue.

“His life mattered,” Mills said.

In addition to chronicling his research on his website and working to create murals and memorials in public spaces, Mills does lectures about his work at schools, universities, libraries, historical societies and museums.

“Students are really compelled and really responsive to him,” said Jesse Nasta, assistant professor in the African American Studies Department at Wesleyan University in Middletown. Both Nasta and Mills are members of the Connecticut Freedom Trail committee, which manages more than 160 historical sites across Connecticut.

Mills has been a guest speaker in Nasta’s classes for the past two years and has made presentations at the Middlesex County Historical Society, also in Middletown, where Nasta is the executive director.

“For him to tell those stories as a direct descendant of enslaved people, it has a different resonance,” Nasta said.

“His work is really important because he shows how one person can make such a huge difference,” Nasta added. “He’s taken it upon himself as an individual to research, uncover and tell untold stories of Black people in the U.S. who have been neglected, unknown and forgotten.”

After confronting his own history, Mills said, he once again feels a sense of pride in his surname – and where it came from.

“My great-great-grandfather lives on in me,” he said. “His story, his plight, gives me reason to do the same as he did; he inspires me to push past obstacles and persist.”