Relocated grizzly bears roaming Yellowstone National Park, FWP data shows

A female grizzly has explored a vast swath of Yellowstone National Park since being translocated to the region in July while her male counterpart has been more of a homebody.

The two bears were trapped by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks staff in a remote area near the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, just south of Glacier National Park in northwestern Montana.

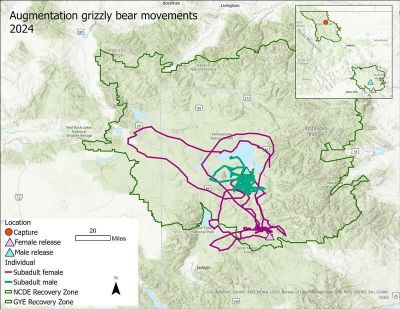

Where the bears roamed was captured by GPS collars the bears are wearing, a map of which was released by FWP on Friday.

“We are very pleased to see that both bears have remained in the (Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem), even staying mostly within remote areas of the Recovery Zone,” said Cecily Costello, FWP grizzly bear researcher. “It’s not always easy for a bear to adjust after being moved like this, but they seem to be settling in. We believe both have recently found a den site for the winter.”

The grizzlies, both subadults, were moved as a way to genetically connect bear populations in two of the animals’ strongholds. The hope is the bears will breed with locals, since the GYE population has been genetically isolated for decades.

Grizzly bears in the Lower 48 are currently protected under the Endangered Species Act, although that could change in 2025 as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is expected to rule on petitions to delist the animals in the GYE and the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, which includes Glacier National Park.

Chris Servheen, who who for 35 years worked as grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the USFWS, released a report this week urging his old employer to manage the two populations, as well as those in the Cabinet, Selkirk and Bitterroot mountains, as one metapopulation to promote genetic connectivity.

Although Servheen said he was pleased to hear the two relocated bears are doing well so far, he said the state of Montana does not “have adequate regulatory mechanisms in place anywhere outside the areas covered by the NCDE and GYE conservation strategies.

“A mandatory requirement of the Endangered Species Act for a species to be recovered and delisted is that adequate mortality management mechanisms and habitat management mechanisms be in place to assure that grizzlies remain healthy and recovered after they are removed from ESA protections,” Servheen wrote in an email. “There are no habitat regulatory mechanisms on public lands or mortality regulatory mechanisms of any kind in the areas between the ecosystems where grizzlies need to be to connect ecosystems.”

FWP said, “Both ecosystems have populations of grizzly bears that have surpassed recovery goals.” The agency also said translocation could occur again, “depending on how close the two populations eventually grow.”

“This just jump starts what very likely will also happen naturally,” said Ken McDonald, head of FWP’s Wildlife Division.

Servheen said natural connectivity between the separate bear populations is unlikely given current FWP management.

“FWP currently allows black bear hound hunting in connectivity areas thus risking grizzly mortalities that will rarely be reported,” he said.

He also noted the agency recently lost a court case that limits trapping to between Jan. 1 and Feb. 15 in grizzly bear core habitat to avoid trapping bears outside their hibernation period.

“However, that ruling is based on listed status for grizzlies,” Servheen said. “If grizzlies were delisted, that federal court ruling would be moot anywhere grizzlies were delisted.”

The two translocated bears were captured and collared within a day of each other southwest of east Glacier in a remote area and driven overnight to the GYE. One was a 3- to 4-year-old female; the other was a 4- to 5-year-old male.

“We were looking for the ideal bears,” McDonald said. “It’s actually not that easy to capture two bears that are prime candidates for translocation.”

In this case, the ideal bears were subadult, meaning they were older than cubs but not at sexual maturity yet, had no history of conflict and weighed enough to prepare for hibernation, McDonald said. Bears of this age are often in search of their permanent home range, therefore they are more likely to stay in the relocation than more mature individuals, the agency said.

FWP worked with partners from the National Park Service and the Wyoming Game & Fish Department on the translocation destinations. The male bear was hauled by boat to the southern end of Yellowstone Lake. The female was taken to a remote location in the Blackrock Creek drainage west of Dubois, Wyoming.

Montana has petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to delist bears in the NCDE. Wyoming, with support from Montana and Idaho, has petitioned to delist grizzly bears in the GYE.

In both ecosystems, FWP said states have met the delisting requirements and addressed concerns identified by the public or outlined by federal courts that have overturned previous delisting efforts.

These elements include: Reaching population recovery; having conflict prevention and response programs in place ; continuing with research and monitoring ; establishing a regulatory framework for managing grizzly bears once delisted; continuing with education and outreach about grizzly bears; and safeguarding genetic health.

In his report, Servheen cited concerns about Montana, Wyoming and Idaho’s “regressive state anti-carnivore policies,” such as reducing wolf populations, as evidence they cannot be trusted to preserve grizzly bears. His report was supported by several other grizzly bear biologists.

According to McDonald, Montana and Wyoming have and will continue to act on their commitment to connectivity, and the agencies will continue to monitor the bears and their genetics to check for population diversity.

“That these bears are exploring their new ecosystem and seem to be doing well is an indication that they’ll thrive in their new environment,” McDonald said. “It also reflects the commitment Montana has to grizzly bear conservation.”

In a talk this summer, Frank van Manen, a U.S. Geological Survey research biologist and leader of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, called connectivity a “non-issue.” He said the greater concern should be about protecting landscapes within both ecosystems from greater development and more recreation.