Invasive mussels found in Washington wholesale store could cost state millions

Watercraft Inspector Derek de Haas walks around a kayak whose owner was headed to the Spokane River on Tuesday at the inspection station at the Idaho state line near the westbound lanes of Interstate 90. (Jesse Tinsley/The Spokesman-Review)

At least 12 invasive zebra mussels were found in aquatic moss balls sold for aquariums in a Renton, Washington, aquatics nursery wholesaler on Aug. 5.

The mussels, which are native to freshwater bodies in Ukraine, are capable of causing significant infrastructural and environmental damage, said Becky Elder, spokesperson for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“We are trying, in every capacity, to make sure that these invasive species do not make it into Washington’s waters.”

Zebra mussels were introduced to the United States in the 1980s, brought over by transoceanic vessels that would empty their ballasts into the Great Lakes, said Cole Morrison, the invasive species program manager for the Idaho State Department of Agriculture. The water contained the microscopic larvae of the mussels, which are invisible to the naked eye, and they found no natural predators in America.

“If you look at those states that have had them for 40 years or so, you’ll see – they say that you can drain the Great Lakes and walk along the bottom and never touch sand because they’re so thick on the bottom of the Great Lakes,” Morrison said.

In 2021, the mussels found a new way to the states – by hitching a ride on Marimo moss balls, which are found naturally in about four Ukrainian bodies of water, Morrison said.

“They’re a kind of free floating algae that form into balls as they get pushed around by the currents of those four water bodies and form these really spherical shapes. So they’re really attractive,” Morrison said. “And for that reason, there was tons of them being sold.”

Justin Bush, invasive species coordinator for WDFW, said that keeping hydroelectric facilities alone running should the mussels contaminate them would cost Washington State $100 million a year.

“The mussels are quite small and they basically continue growth on top of the previous generation. And so, thinking about a pipe over time, the dead mussels as well as the new generation on the top will close off pipes and stop the flow of water,” Bush said. “Thinking about small-diameter pipes in any sort of water infrastructure, that’s a recipe for disaster – the systems may not have been developed in a way that you can easily clean that out.”

Morrison said that the real worry is that someone would dump a tank with a contaminated moss ball.

“They’re maybe tired of the upkeep of the aquarium, or they think they’re being nice and wanna let Nemo back into what they think is his natural environment, and take them down to the river and dump them in,” Morrison said. “That was our big vector concern.”

Elder said that there is no indication that any moss balls from the 2021 incident were released in Washington, and that federal policies were implemented afterwards to try and limit the importation of infected Marimo moss balls.

Morrison said that even if 90% of their annual offspring die, a single breeding pair of zebra mussels can result in the establishment of a septillion mussels within their 3- to 5-year lifespan. Their large numbers mean that they eat everything in the water that the bugs at the bottom of the food chain normally eat, which has cascading impacts on fish and wildlife populations. The result is a lake that some observers have described to Morrison as being clean and clear.

“I always tell them that it’s less that it’s clean and clear, and more that it is sterile,” Morrison said. “And when you’re talking about a wild environment, sterile is bad. I want my kitchen table to be sterile, I don’t really want rivers and lakes and all that sort of stuff to be sterile.”

Marimo moss balls in pet stores around Washington and Idaho are currently being inspected for the presence of zebra mussels, according to multiple news releases. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Idaho State Department of Agriculture ask the public to inspect their aquariums if there is any chance of contamination in the releases.

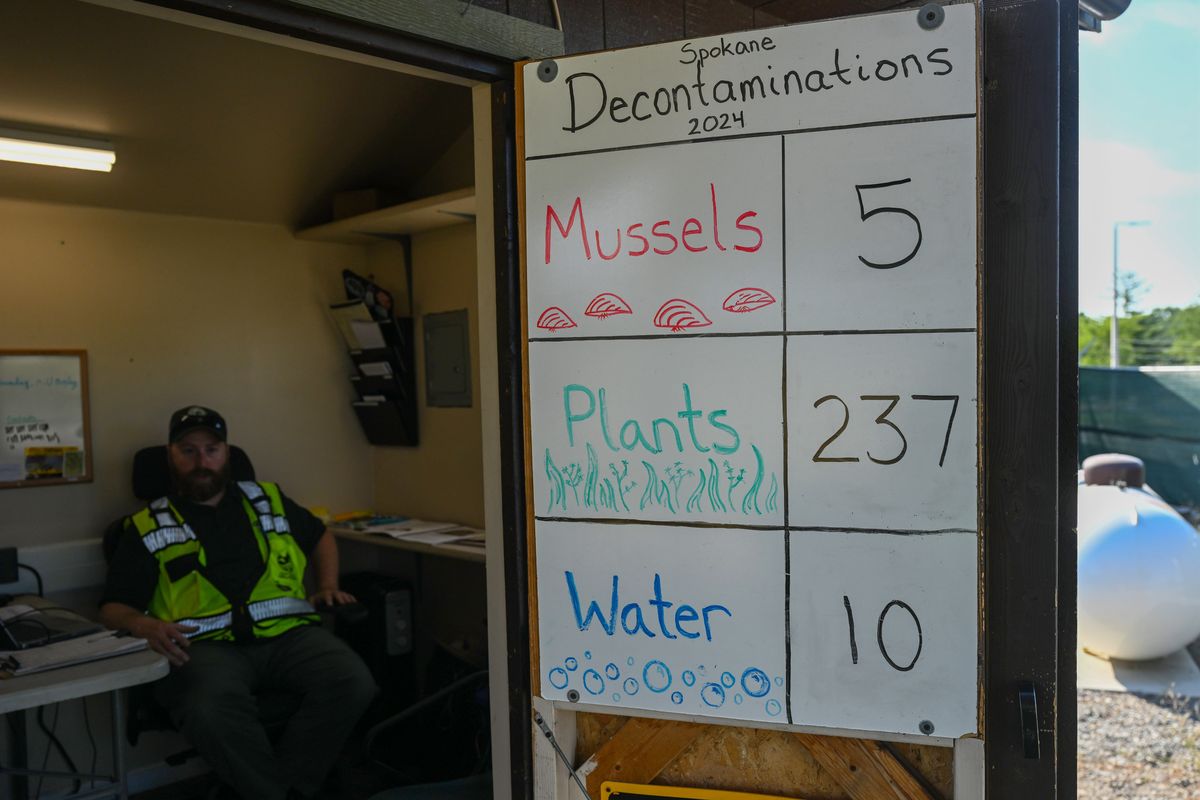

Derek de Haas, WDFW watercraft inspector and decontaminator just outside of Stateline, is responsible for ensuring zebra mussels and other invasive species do not come into Washington on boats.

Zebra mussels can survive for around 23 days out of the water in proper conditions, de Haas said, so if they are found on a boat, they may still be alive.

In order to dispose of mussels, the boat is first hosed down with 140-degree water in order to kill any that are still alive. Then, the shells are removed from the boats with 120-degree high-pressure water. The shells must be collected and disposed of afterwards, as their DNA in a body of water can lead to false positives in tests for the mussels’ presence, de Haas said. Boats are then given a seal, which must stay on for 30 days.

This year, five invasive mussels have been found and removed at the station. This is a stark improvement from previous years – a difference to which de Haas credits the increased efficacy of watercraft check stations in the region.

The watercraft inspections are free, though those who do not stop run the risk of being pulled over and charged a $150 fine.

Zebra mussels on Marimo moss balls can be disposed of in a similar way – by boiling for a minute before throwing in the trash. Moss balls can also be decontaminated by freezing for 24 hours or soaking in white vinegar for 20 minutes before disposal, according to the Invasive Species of Idaho website. Hot water, a 24-hour salt soak, or diluted bleach mixture can be used to decontaminate the aquarium and accessories themselves.

“It’s a fearful concern that we have that’s very real – that’s in essence kind of knocking at our door,” Elder said. “And we need to be on the front lines to continue to make sure that this doesn’t get into our local waterways.”

This article has been updated to reflect that the 12 mussels found in Washington were located in an aquatics nursery wholesaler, not a Petco.