Former Mayor Richard Daley expected to be in Chicago for DNC but keeping it ‘low key’

CHICAGO — When Chicago last hosted the Democratic National Convention in 1996, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley was the king of the city as he welcomed delegates, gave speeches all around town and did all he could to show that Chicago was ready for prime time.

“In this city of the century, one person has brought together visitors from across the nation and around the world. They have found not only a city with beauty, they have found a city with a heart,” U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, then a downstate congressman, told a crowd of Illinois delegates gathered at the Drake Hotel. “This is a convention city with a new spirit and a new generation of Democratic leadership.”

It was the third day of the DNC and Daley, underscoring his important role as chief emcee of the convention, was about to introduce Hillary Clinton, then the first lady and an Illinois native before she gave a rousing speech to hundreds in attendance.

Now 28 years later, Daley is expected to be in Chicago for the DNC again — but this time in a much different role. The longest-serving mayor in Chicago history and son of Richard J. Daley, the mayor in 1968 when the Democratic convention was marred by what a subsequent report deemed a “police riot” against protesters, Richard M. Daley is expected to attend DNC events but will keep a “low profile,” said his brother, Bill Daley.

In fact, it wasn’t even clear until just a few days ago that the younger Mayor Daley would show up at all, an absence that would have been notable given how the 1996 Democratic convention exorcised many of the ghosts of his father’s 1968 convention.

“Knowing Rich of late, it will be very low key,” said Bill Daley, a point man for the 1996 convention who served in President Bill Clinton’s cabinet and as President Barack Obama’s chief of staff.

Since leaving office in 2011, Richard Daley, 82, has lived a much less-public life and kept out of the spotlight. Two years ago, he spent days in the hospital and in rehab after experiencing what his doctor called a “neurological event.” In 2014, he was admitted into intensive care after taking a fall. He reportedly suffered stroke-like symptoms that affected his speech.

Bill Daley said he also expects to attend some of this year’s DNC events along with his brother John, a Cook County Board commissioner. He didn’t detail when or where his brother the former mayor will appear this year but noted how important it was that Chicago pulled off a successful convention in 1996, adding a “debacle” back then would have made it tough for Chicago to land this year’s DNC.

“Then the odds of bringing it here would be zero,” Bill Daley said.

But demonstrations in 1996 were mostly peaceful and Democrats happily renominated Bill Clinton, who went on to easily win a second term.

“It was a big relief when everybody left and there were no issues and no crises,” Daley said. “Yeah, it was like, ‘Whew! Done! You know?’”

“The city was on a big roll then,” Daley added. “The economy was good. The business community really stepped up. Obviously, there was a lot of desire to put ’68 behind us.”

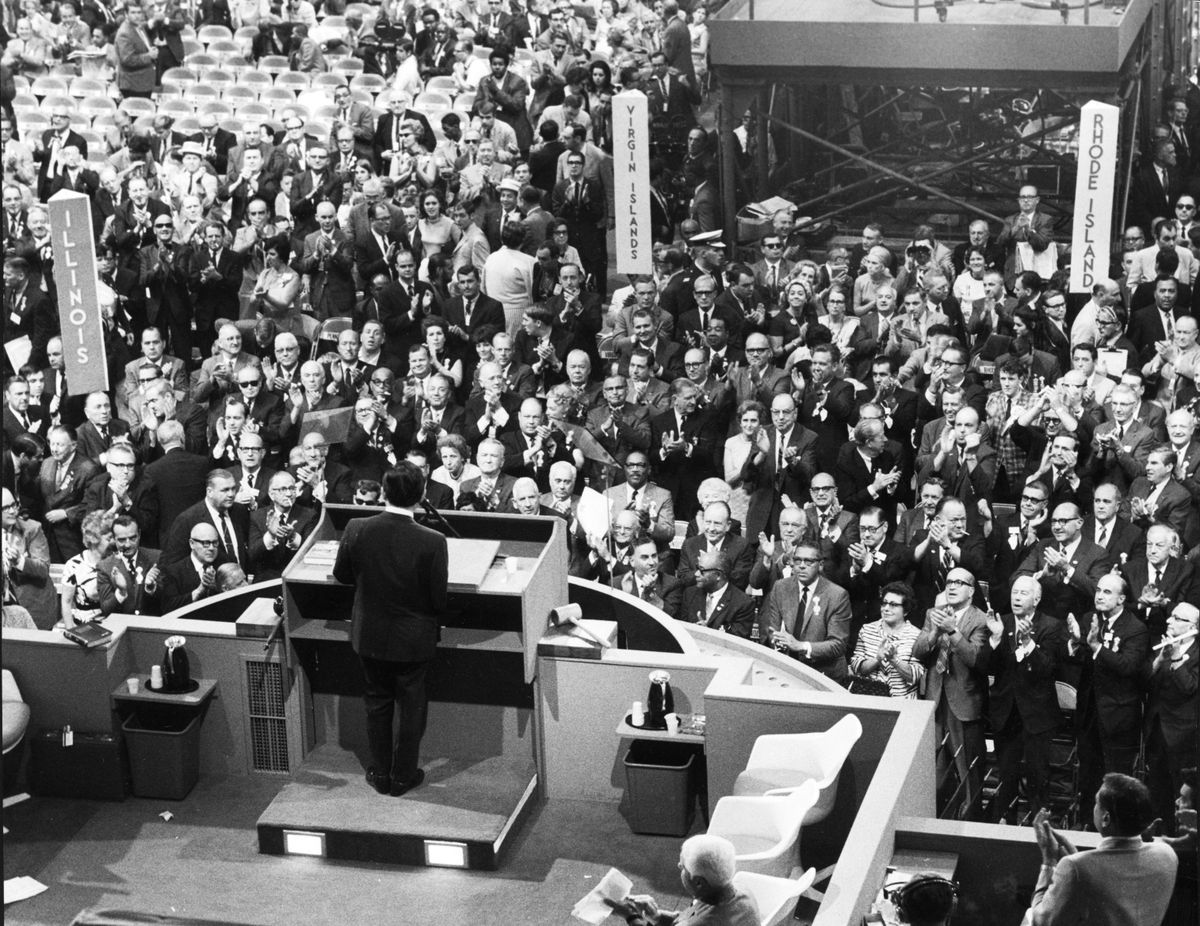

The 1968 DNC came at one of the nation’s most divisive times as the war in Vietnam continued to rage and protesters arrived in Chicago wanting to have their voices heard and policies changed. Police responded and violence erupted with officers whacking often unarmed protesters with billy clubs at skirmishes downtown, most notably in front of the Hilton Chicago hotel.

Mayor Richard J. Daley — father of Richard M., Bill and John, as well as other children — took most of the national heat for the police response, though Chicago voters years later reelected the elder Daley by wide margins to two more terms.

In 1996, aides to Mayor Richard M. Daley recognized the stakes were high for the DNC, acknowledging the historical nexus between the father and son both being mayor, yet also the opportunity for the son to change the city’s narrative.

“I do not think that there would have been another (political convention) if ’96 had been crazy,” said Avis LaVelle, a press secretary for the second Mayor Daley and later campaign manager for his 1995 reelection campaign. LaVelle worked at the 1996 convention to coordinate interviews between reporters and politicians and recalled the overall feeling that “there was a lot riding on Chicago’s ability to execute well.”

One major factor in Chicago’s favor in 1996 was an “astonishing level of support” throughout Chicago’s neighborhoods and the region overall, said Leslie Fox, the point person for the Chicago host committee in 1996.

“There was convention fever,” she said. “Chicagoans stood together and said, ‘We do not want the footage of ’68 to define our city to an international audience, and anyone who has a stake in the city felt that.”

Forrest Claypool, who served as Daley’s chief of staff and who helped prepare for the 1996 convention as head of the Chicago Park District, said, “The 1968 experience seared a scar on the country, on the Democratic Party, on the city of Chicago.”

“I think a lot of people felt that contributed to Hubert Humphrey’s loss in 1968 and also sort of put Chicago out of the convention business for a long time,” he said. “Bill Clinton, though, because of what Mayor Daley had done to turn around Chicago, brought it back in 1996 for his renomination.”