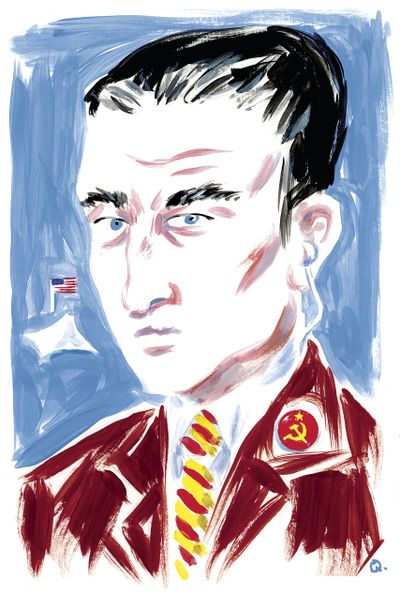

Summer Stories: ‘The Princeling’s Keeper’

By Samuel Ligon

My people could not believe they’d ever tire of your M&M’s or Marlboro cigarettes or brightly lit stores filled with whiskey and vodka – too much, even for Russians to drink. Or the disgrace of your President Nixon. Or the heroism of your Patty Hearst. Or the empty pleasure we took in your Kojak and Hawaii Five-O and Days of Our Lives. We fell in love with your distractions even as we knew you were a decadent people, spoiled and fat and sometimes unbearably innocent and often as stupid as salted slugs, but also evil – some of you – all the way through.

I was there to protect them from you and themselves, to keep them out of trouble, especially Ilya Ivanovich Malakhov, the most beautiful boy I had ever seen. And should he make a mess, I was there to clean up after him, as I’d done in Munich and Brazil. But we were in your city so long it was impossible to keep our appetites in check. Even I was seduced, perhaps because Ilya was so enchanted by your Exposition, a months-long affair filled with cowboys and Indians and sky rides and fireworks and so many lovely girls and boys falling in love with him.

I watched as he slept off his indulgences, our room filling with vapors. Still here, I would think, touching his forehead. Still with us. I’d touch his cheek, his hair, his chest rising and falling. There was no way out but through me, and he would never get through me. Or Nikita or Gurov, who would watch on my days off or when I was otherwise indisposed, all of us watching each other and being watched, the strength of our nation and our greatest weakness.

I watched him at breakfast and in the beer garden at night after the exhibitions closed. He was more beautiful even than your Elvis – because of his poet’s soul and delicate mouth and the radiance with which he blessed the objects of his attention, as if they were the most delightful creatures on earth. Except for me, who he refused to see at all, unless absolutely necessary. Or unless drunk.

“You want to watch me with the gypsy boy, Pavel Romanovich? Is that why you follow me like a dog? Filthy old man. You should have been killed by the fascists in Stalingrad.”

His uncle Nikolai Dmitrich was a rising star in the communist party, a reformer, at least privately, who wanted Ilya to be free in a way he would never be in our country, as long as he was discreet – even in your land of the free. Such a ridiculous lie. Only prisoners or children would cling to such a fairy tale. And when you saw his real freedom, you were terrified.

The radio played songs of the Carpenters for weeks before they performed in your Opera House. When they finally stepped onstage, alive and in person, Ilya was in front with a girl named Tammy and her lover, Stan, a Husky of the Washington football club. Ilya usually chased after dove boys, but anyone might attract him. Tammy leaned into him as he whispered in her ear, Ilya watching the Husky over the girl between them. I sat five rows back, sinking into the music. The Carpenter woman reminded me of Sasha when we were young in Volgograd, what we still called Stalingrad then, the miracle of life coming back to me as she led me into the water.

Onstage, the Carpenter sang, Don’t you remember you told me you loved me baby?

If you have not seen your brother shot in the street or your mother and father blown into pieces you could pick up and hold – if you have not seen a cat on fire running for the river – you cannot fathom what the fascists did to us in Stalingrad. And what we did to them. And each other. We killed our cowards and stragglers and deserters to save the world, to give you your Pax Americana. And how did you thank us? With a never ending threat of annihilation.

But you were beautiful, too. Like Ilya.

Beautiful, rich children, most of you.

Protected by goons.

The Carpenter closed her eyes. You’re not really here, she sang. It’s just the radio.

The first day I spent with Sasha, she led me into the Volga laughing and splashing and diving into the water. How was it possible anyone could laugh like this? “Become a seal, Pavel Romanovich,” she told me. “Become an otter.” I was too old for this kind of play, five years after the war, when everyone I’d ever loved was dead. But I swam after her. “Become a sturgeon, Pasha,” she called. And just as I’d think I could reach out and touch her, she’d swim away, leading me to the rougher water under the falls, where she finally let me catch her and hold her, laughing as she wrapped herself around me.

She’d seen everything I’d seen and worse, but she still found delight in the world. Even later, as cancer devoured her, she had moments of joy to share with me and the children.

Don’t you remember you told me you loved me baby?

Of course I remembered.

“Become a bear, Pasha,” she said. “Even grown children are just children.”

Yes, they would always be children, their lives so much easier than ours.

But they were also adults now – and would never be children again.

The music filled me with Sasha and the children and my mother and father, with Ilya and wanting to touch him – if only to get close to his brightness, his cruelty and joy.

When the Carpenter finished her sad song, Ilya and his new friends were gone.

I pushed my way out, scanning the aisles, the lobby, the lavatories, knowing I would never find them. Whatever happened now I deserved. Outside the fireworks were exploding over the pavilions – Korea, General Motors, Germany, Japan, the whole city hiding them, the whole world.

I kept walking, sweating through my suit.

What a self-indulgent fool I’d become.

Only a week before, Liberace had performed on the same night Olga Korbut tumbled in your coliseum. I insisted Ilya see her, though I would have to watch him in the event he tried to lead her to the People’s Park, a Soviet sounding name, where your hippies had tents and free love, so many of them naked in the water. He eluded me that night, but I found him soon enough in the beer garden with Liberace’s boy. I followed them over the roaring falls toward the Boy Scout encampment, Ilya looking back and laughing, taking so much joy in hurting me.

But he was not in the beer garden now. I stopped on the bridge and smoked a cigarette, the water crashing below, splashing up to where I stood. How many cigarettes would I have left in my life? I’d been winding down for months, as though I could see what was coming even before I heard the girl’s cries, as though weeks had passed and I was already back in Moscow awaiting my punishment. I flicked my cigarette into the falls and saw Gurov watching from one end of the bridge, Nikita from the other.

There was a boy I’d weighted and put in the river in May, his body surfacing only days ago. There was nothing connecting him to us. There was another from June who hadn’t yet surfaced. Boys Ilya had hurt, who could implicate him, and by extension all of us. I took no pleasure in killing them, though Ilya took pleasure in hating me for doing my job. Standing over the falls I did not know when I’d come to understand that there was no way to win a war against so many cigarettes and hamburgers and washing machines. But I understood now.

Gurov and Nikita did not. They were still so young and attached to life.

The reds and blues of the fireworks streaked around us.

In Stalingrad we fought in sewers and crumbling factories for the city’s rubble, and when Hitler’s starving army finally surrendered, their comrades’ bodies were rotting in piles across the steppes. If one survives, as I did, living becomes your punishment, unless you somehow find yourself years later with a baby asleep on your lap, your son on the floor at your feet playing, your wife beside you, warm and drowsy, whispering with her touch: Do you see what we’ve done, Pasha – this miracle we’ve created?

Yes, you see.

But, still, life must end. Perhaps in the churning below.

When the girl cries out – so quietly, so close – you walk toward Gurov watching you.

“Go back,” you say to him. “Watch the others.”

Nikita joins the two of you. “And who will watch you, Pavel Romanovich?”

“Nobody,” you say.

“You might need assistance,” Gurov says.

Another cry – or maybe just shrieks from the carnival rides.

“This is an order,” you say.

The goons look at each other.

“Do not follow,” you say.

Fireworks whistle around you.

“The boy’s uncle will have your heads.”

You run toward the north bank and onto a path alongside the river.

You hear fireworks and the roaring falls upstream. And then whimpers.

“Stop,” she says, so close now.

“Please,” she whimpers.

The boy must already be dead.

Ilya soothes her with “Bayu Bayushki,” his voice so sweet over her whimpering: “Hush a bye, sleep tight / Don’t lie near the edge of the bed, else a little wolf will come.” It’s the same lullaby your mother sang to you, that Sasha sang to your children. “A little wolf will come and take you with his teeth. And drag you into the forest.”

You make your way around a thicket of brambles and come upon them on the ground in a tight clearing. Their clothes are gone and they’re covered in scratches and bruises, dirt and blood. Her eyes have already faded, but he watches you with a knife to her neck as he cradles her, bleeding her, the crumpled, naked boy beside them nearly beheaded. She is almost asleep. Ilya lets you settle behind them, wrapping them in your arms. He’s warm against you and trembling, the girl cooing as Ilya soothes her. When he finishes, you will put him to bed with the boy and the girl, hiding them in water where no one will find them. And then you will find your own place to rest, thousands of miles from Moscow and Volgograd, a quiet place close to Ilya in the land of the free.